My recent post on Nephi’s three-day journey, the leg of Lehi’s Trail that reaches the River Laman in the Valley of Lemuel, discussed the significance of Exodus themes in Nephi’s account and why Nephi would give special emphasis to that particular leg of an eight-year trip. In response to several questions from readers, I see a need to share a few more details that might help some better appreciate some meaningful details in Nephi’s account.

A key issue to address is whether the three-day journey begins near the Red Sea at a place near the northern end of the Red Sea such as Aqaba, or whether the three days began upon leaving Jerusalem. Latter-day Saint readers have generally read 1 Nephi 2 to mean that the three days began at the northern tip of the Red Sea, but the heading to 1 Nephi may make it seem like the count for the travel to the River Laman began at Jerusalem. We’ll consider both passages in a moment, but let’s first consider the three-day journey in the Exodus.

Many writers have noted that Nephi’s agenda included deliberate highlighting of parallels to the Exodus. See, for example, Terry L. Szink’s “Nephi and the Exodus” in Rediscovering the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS, 1991), 38-51. Like Moses leading Israel out of Egypt to the promised land, Nephi’s people are taken out of spiritual “captivity” in Jerusalem and imminent physical captivity shortly before the Exile. They are led into the wilderness toward the promised land by a prophet of God (Lehi initially, and then Nephi) with miraculous assistance. One significant part of both the Exodus account and Nephi’s account is a three-day journey. Moses initially made a request to Pharaoh to let his people go on a three-day journey into the wilderness or desert to offer sacrifice, but this was declined (Exodus 3:18; 5:3; and 8:27). After the plagues upon Egypt forced Pharaoh to let Moses and his people go, Moses would lead his people across the Red Sea. After that miraculous crossing, Exodus 15 describes a three-day journey from the Red Sea to Marah, where water would be miraculously provided (see also Numbers 33:8, which confirms a three-day for the journey from the Red Sea to Marah). Here is the account from Exodus 15:22-27:

22 So Moses brought Israel from the Red sea, and they went out into the wilderness of Shur; and they went three days in the wilderness, and found no water.

23 And when they came to Marah, they could not drink of the waters of Marah, for they were bitter: therefore the name of it was called Marah.

24 And the people murmured against Moses, saying, What shall we drink?

25 And he cried unto the LORD; and the LORD shewed him a tree, which when he had cast into the waters, the waters were made sweet: there he made for them a statute and an ordinance, and there he proved them,

26 And said, If thou wilt diligently hearken to the voice of the LORD thy God, and wilt do that which is right in his sight, and wilt give ear to his commandments, and keep all his statutes, I will put none of these diseases upon thee, which I have brought upon the Egyptians: for I am the LORD that healeth thee.

27 And they came to Elim, where were twelve wells of water, and threescore and ten palm trees: and they encamped there by the waters.

So after crossing the Red Sea, Moses leads the people on a three day journey. There was no water at first, and when they then found water at Marah, it was not drinkable. However, the Lord performed a miracle by having Moses cast a tree into the water that caused the bitter waters to become sweet. This seems to be parallel to Nephi’s description in 1 Nephi 2 of traveling three days from near the Red Sea to a surprising river of water, thanks to miraculous guidance from the Lord. The miraculous provision of water in Exodus 15 was given special emphasis with a “statute and an ordinance” (v. 25), and the Lord covenanted that if they would hearken to His voice and keep his commandments, He would spare His people from the plagues He had put upon the Egyptians (v. 26), similar to the promise made to the Nephites: “Inasmuch as ye shall keep my commandments ye shall prosper in the land” (2 Nephi 1:20; also see 1 Nephi 2:20, 4:14, 13:15,20; 2 Nephi 1:9, 4:4; Jarom 1:9; Omni 1:6; etc.). After this, they come to a place with twelve wells of water and 70 palm trees, “and they encamped there by the waters” (Exodus 15:27).

The heading of 1 Nephi needs to be considered in light of Nephi’s intentions and his desire to liken his journey to the Exodus:

An account of Lehi and his wife Sariah and his four sons, being called, (beginning at the eldest) Laman, Lemuel, Sam, and Nephi. The Lord warns Lehi to depart out of the land of Jerusalem, because he prophesieth unto the people concerning their iniquity and they seek to destroy his life. He taketh three days’ journey into the wilderness with his family. Nephi taketh his brethren and returneth to the land of Jerusalem after the record of the Jews. The account of their sufferings. They take the daughters of Ishmael to wife. They take their families and depart into the wilderness. Their sufferings and afflictions in the wilderness. The course of their travels. They come to the large waters. Nephi’s brethren rebel against him. He confoundeth them, and buildeth a ship. They call the name of the place Bountiful. They cross the large waters into the promised land, and so forth. This is according to the account of Nephi; or in other words, I, Nephi, wrote this record.

The wording in the header exactly follows the KJV language when Moses asks Pharaoh to let them “go … three days’ journey into the wilderness” (Exodus 3:18, 8:27) and closely follows Exodus 15:22’s “they went three days in the wilderness” after they escaped from Egypt and crossed the Red Sea. Given the many other instances in which Nephi alludes to the Exodus, it is reasonable to conclude that this is deliberate. The three days’ journey is important enough to be one of the few details that are placed in the compact header. But since the previous sentence mentions the warning to depart out of the land of Jerusalem, must we understand the sentence about the three-days journey to begin at Jerusalem?

Note that Nephi does not say in the header nor in the text of 1 Nephi that the three days began in Jerusalem. My proposal is that the header and the text in 1 Nephi 2 better fit Nephi’s authorial intent if understood as starting at the Red Sea, and that the three-day journey in 1 Nephi 2 reads most logically as beginning at the Red Sea. So let’s turn to 1 Nephi 2:5-7, and not only note the language used to describe travel near the Red Sea, but also the distinction Nephi appears to make with the verbs “depart” and “travel”:

2 And it came to pass that the Lord commanded my father, even in a dream, that he should take his family and depart into the wilderness.

3 And it came to pass that he was obedient unto the word of the Lord, wherefore he did as the Lord commanded him.

4 And it came to pass that he departed into the wilderness. And he left his house, and the land of his inheritance, and his gold, and his silver, and his precious things, and took nothing with him, save it were his family, and provisions, and tents, and departed into the wilderness.

5 And he came down by the borders near the shore of the Red Sea; and he traveled in the wilderness in the borders which are nearer the Red Sea; and he did travel in the wilderness with his family, which consisted of my mother, Sariah, and my elder brothers, who were Laman, Lemuel, and Sam.

6 And it came to pass that when he had traveled three days in the wilderness, he pitched his tent in a valley by the side of a river of water.

7 And it came to pass that he built an altar of stones, and made an offering unto the Lord, and gave thanks unto the Lord our God.

The account begins in the land of Jerusalem, from which Lehi is commanded to “depart into the wilderness” (v. 2). He then “departed into the wilderness” (vs. 4). With seeming redundancy, Nephite immediately adds that Lehi took his family and that they “departed into the wilderness” (v. 4). Then they “came down” by the “borders near the shore of the Red Sea” (v. 5). Only then does the verb “travel” appear for the first time in Nephi’s account. Once near the shore of the Red Sea, they “traveled in the wilderness in the borders which are nearer the Red Sea” (v. 5). That is emphasized, apparently unnecessarily, in the next phrase: “and he did travel in the wilderness with his family” (v. 5), and again in the next verse: “when he had traveled three days in the wilderness, he pitched his tent in a valley by the side of a river of water” (v. 6). We already know that Lehi departed with his family from vv. 2 and 4, so why reiterate that his travel in the wilderness was “with his family” (v. 5)? Was Nephi just a sloppy writer with so much redundancy, or a careful architect of text? I suggest there is architecture at play.

The passage above has “depart[ed]” + “in the wilderness” three times, regarding Lehi with his family, and then “travel[ed]” + “in the wilderness” three times, again for Lehi with his family, and that action of traveling in the wilderness last three days, making it a “three days’ journey” as described in the header. These two parallel parts suggest that Lehi and his family departed into the wilderness and then came down near Red Sea. At that point, they “traveled in the wilderness” in a new place, beginning “in the borders which are nearer the Red Sea” and ending up in what can only be described as a miraculous place even in this day, a place with a river of water in a region long thought to have no rivers apart from temporary flows after rain. That second leg lasted three days. Nephi, seeing the obvious significance of a three-day journey from the Red Sea to a place with miraculously provided fresh water, seems to have chosen to highlight this important parallel in his header. There is no reason to assume that this journey had to begin at Jerusalem. It makes more sense and reads more naturally in 1 Nephi 2 if understood to be a leg that began near the Red Sea.

Further, just as Moses was leading Israel from the Red Sea to the waters of Mara, Lehi wasn’t traveling alone, but was bringing a future part of the house of Israel on a journey to the New World. The repeated emphasis on Lehi bringing his family, and even naming each of them in the midst of defining the three-day journey, reminds us of Exodus 15:22: “Moses brought Israel from the Red sea….”

Adding to the parallels with the Exodus account, sacrifices are offered after this three-day journey, echoing the request Moses made of Pharaoh to go travel three days in the wilderness to offer sacrifices (Exodus 3:18; 5:3; and 8:27).

Understanding the relationships between Nephi’s three-day journey and the ancient Exodus account helps us appreciate the rhetorical tools of Nephi in framing his story and teaching us important lessons. But that’s not the reason this little detail is drawing attention from critics who insist on starting the three-day clock in Jerusalem. They would prefer to demolish what has become an impressive body of evidence for the ancient authenticity of the Book of Mormon into evidence that the story of Lehi’s Trail is impossible due to Joseph Smith’s sloppy work and ignorance of distances.

Is the Three-Day Journey to a River Near the Red Sea Possible?

While it may make interesting allusions to the Exodus, does Nephi’s account of travel to the Valley of Lemuel and the River of Laman have any foundation in reality? Is there any such place within a three-days’ journey from the northern end of the Red Sea? Or any such place three days from anywhere in the Arabian Peninsula? Until recently, the answer was simple: no, for there are no rivers in the Arabian Peninsula, and absolutely no candidate that could come close to qualifying as the River Laman. As often happens, though, apparent great weaknesses in the Book of Mormon have a strange tendency to eventually become powerful evidences for its authenticity. (Faith and patience are a vital combination in dealing with the attacks of critics.)

A breakthrough in understanding the physical reality of Lehi’s Trail came with a publication by George D. Potter, “A New Candidate in Arabia for the Valley of Lemuel,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 8, no. 1 (1999): 54–63, which described finding a potential candidate for the River Laman in Wadi Tayyib al Ism. This was followed by fieldwork to see if that promising site could be reached by following Nephi’s directions starting near the north end of the Gulf of Aqaba. This resulted in a book by George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New, Documented Evidences That the Book of Mormon is a True History (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, 2003). Potter and Wellington began a journey in a jeep in Aqaba at the north end of the Red Sea and traveled south to Haql on the coast, then further south until they turned east into the mountains for a few miles, then went further south and had to choose between a route going further east or driving into a wadi going west. Heading to the west into Wadi Tayyib al Ism, as it is known today, brought them into a granite valley where they encountered a small stream — one that would prove to flow all year round, consistent with Lehi’s phrase “continuously running” in 1 Nephi 2:9 (though they may not yet have had evidence of its persistent flow when Lehi spoke those words). Here’s one view of this stream, which is much smaller than it must have been in the past due to the local government extracting a portion of the water source and possibly due to changes in climate, from George Potter’s work:

Potter and Wellington reached that stream at Wadi Tayyib al Ism in under 75 miles from Aqaba, which is a reasonable upper limit for the distance that one can travel in three days with camels under normal circumstances (about 25 miles a day maximum, though it may be possible to travel further if one travels both day and night). The stream currently disappears into the ground near the shore of the Red Sea. Perhaps it did so long ago when the stream was stronger, or visibly reached the Red Sea rather than subterranean waters feeding feeding the Red Sea, or its “fountain” (1 Nephi 2:9). However, even today with a portion of the water supply being pumped away by the government, the steam does reach the Red Sea directly during the wetter times of the year, as shown in this photo from Book of Mormon Central’s article, “Book of Mormon Evidence: The Valley of Lemuel,” Nov. 28, 2020:

Of critical importance, this candidate for the River Laman is a “river” (a stream to us, but a river in the desert lands of the Arabian Peninsula) that was not supposed to exist and lies within the scope of a three-day journey from Aqaba. It is on an accessible path that a group traveling by camel could have followed on an ancient three-day journey. It’s remarkable physical evidence for the plausibility of the Book of Mormon, or at least for the account of Lehi’s Trail.

If you insist that the three-day journey had to begin in Jerusalem, then the distances don’t work out. The distance from Jerusalem to Aqaba is over 150 miles. Reaching Wadi Tayyib all Ism would then require impossibly fast travel. Nephi’s story would then appear to be evidence against the Book of Mormon rather than for it. But as explained above, the text does not require impossibly large distances to be covered in three days.

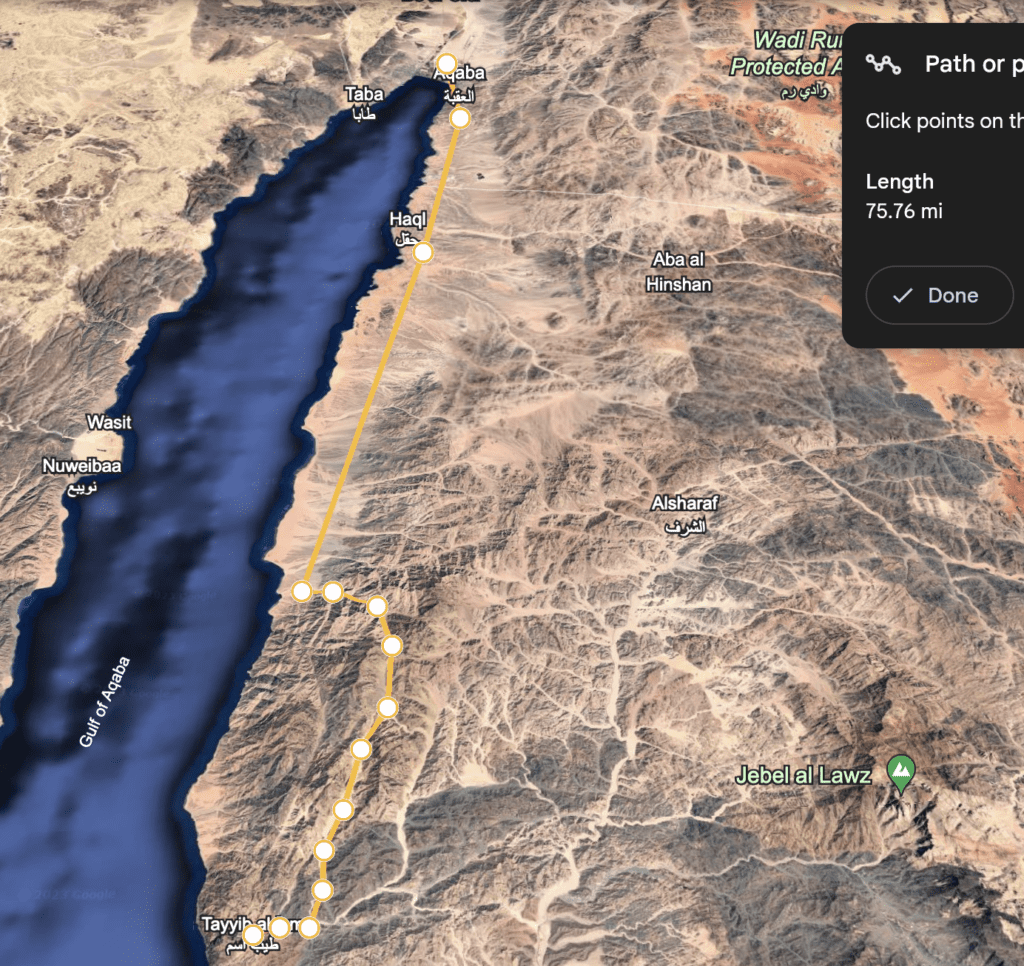

In addition to arguing that the three-day journey must begin at Jerusalem, Dan Vogel in his comments on my prior post has argued that the distance from Aqaba to the River Laman candidate is actually 88 miles, and claims that George Potter started his journey from a port 16 miles south of Aqaba. I’m not sure how he came to these conclusions. Potter wrote in his book that his exploratory trek began in Aqaba, but exactly which part is unclear. While I think there is an error in his report of the distances from Aqaba to Haql and from Haql to the eastward turn into the mountains, the reported overall distance of just under 75 miles is reasonable, though I obtained 75.76 miles for a route that begins on the north side of Aqaba by using the Google Earth “path” tool. My route followed what appeared to be reasonable wadis and smooth paths but I may have gone further east than Potter and Wellington did. They also may have started closer to the southern boundaries of Aqaba. But frankly, if they had to travel a few miles over the “normal” limit of about 75 miles by sleeping less and traveling longer than normal on the third day, for example, I don’t think that’s a serious problem. if the ideal route turns out to be 80 or 85 miles from Aqaba, or if we have to assume Nephi started their three-day journey a few miles south of Aqaba, it’s not a fundamental problem. There’s an amazing candidate for the River Laman and the Valley Lemuel that can fit the guidelines of the Book of Mormon. Arguing that it might have required a few miles more than 75, or that the river doesn’t quite reach the Red Sea in the dry times of the year (in our era) is quibbling over minor details while ignoring the stunning important of the find at Wadi Tayyib al Ism: an unexpected river flowing to the Red Sea in an impressive valley that is accessible from the northern end of the Red Sea in a three-day journey.

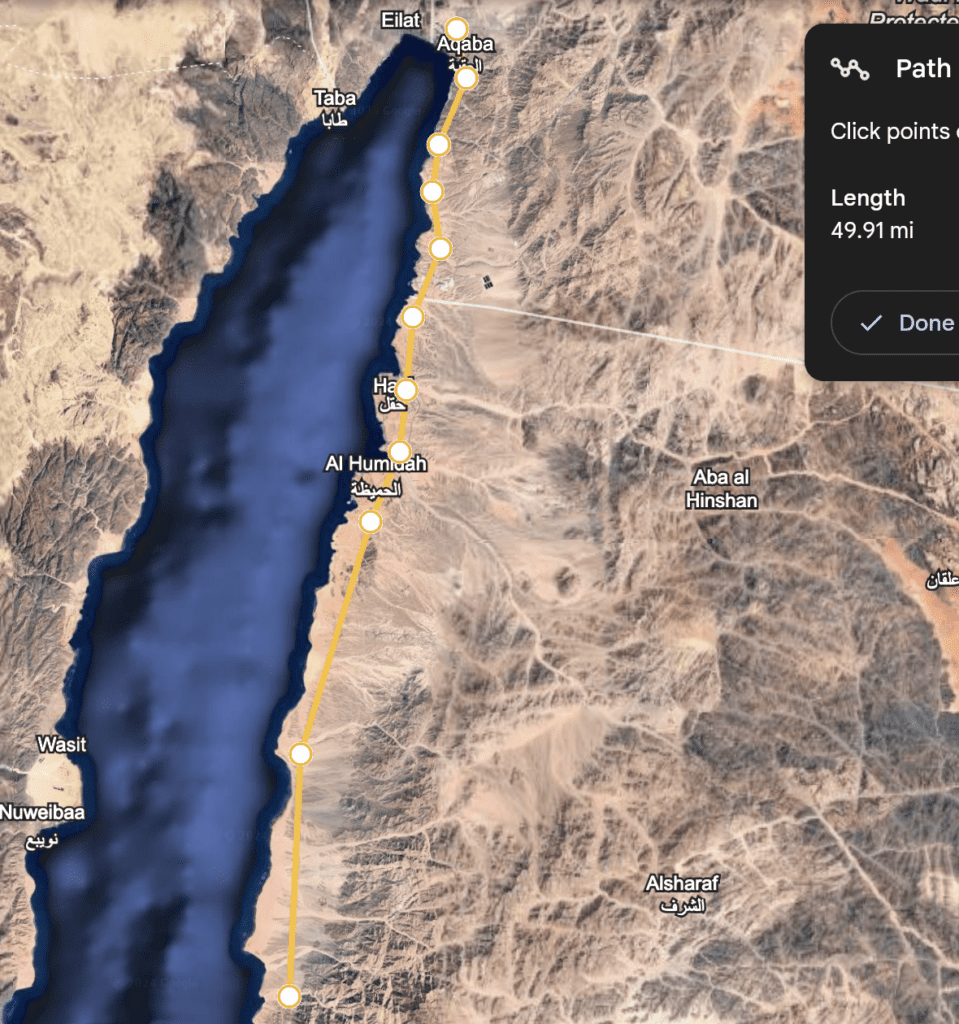

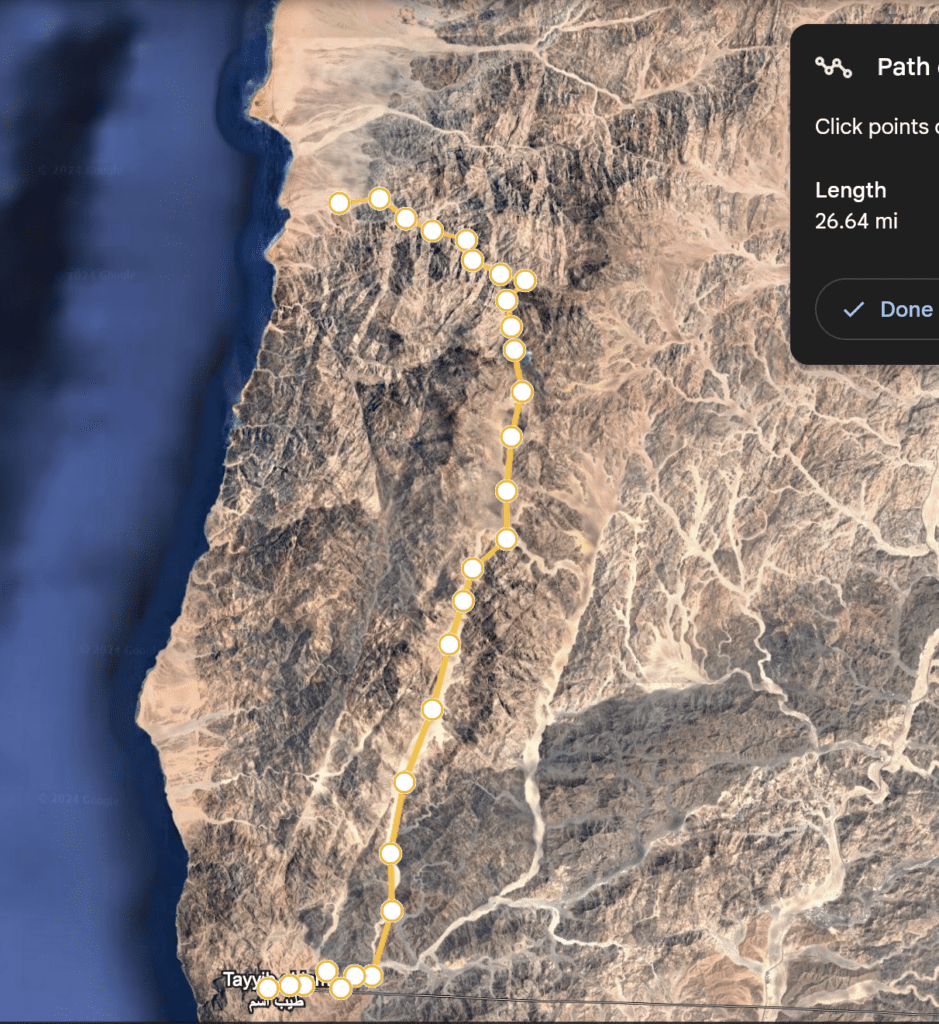

Next I show a slightly different approach done at higher resolution for the lower part of the trek to better represent what I think might be a plausible route. First I show the easier, relatively flat part of the journey near the coast, taking about 49.9 miles, and then the trek through the mountains, taking about 26.6 miles, for a total trip of 76.5 miles (less if we start on the southern side of Aqaba, a couple miles further south). For the mountainous route, by the way, Google Earth allows you to see elevation along the path. The route I have marked gets as high as about 4,000 feet above sea level before descending again, but seems to avoid any sudden cliffs or impassable portions, and when zoomed in sufficiently, there’s even a local government office listed in the middle of the southern leg, not far after the high point, which might suggest that the route is indeed drivable. (I’m guessing the water is related to water management.) Here are the results from Google Earth:

As I look at these maps now, I can see room for improvement in better following the route that might add half a mile to the distance. I also would like to add information about elevation along the way, but that’s easy for the reader to check with Google Earth

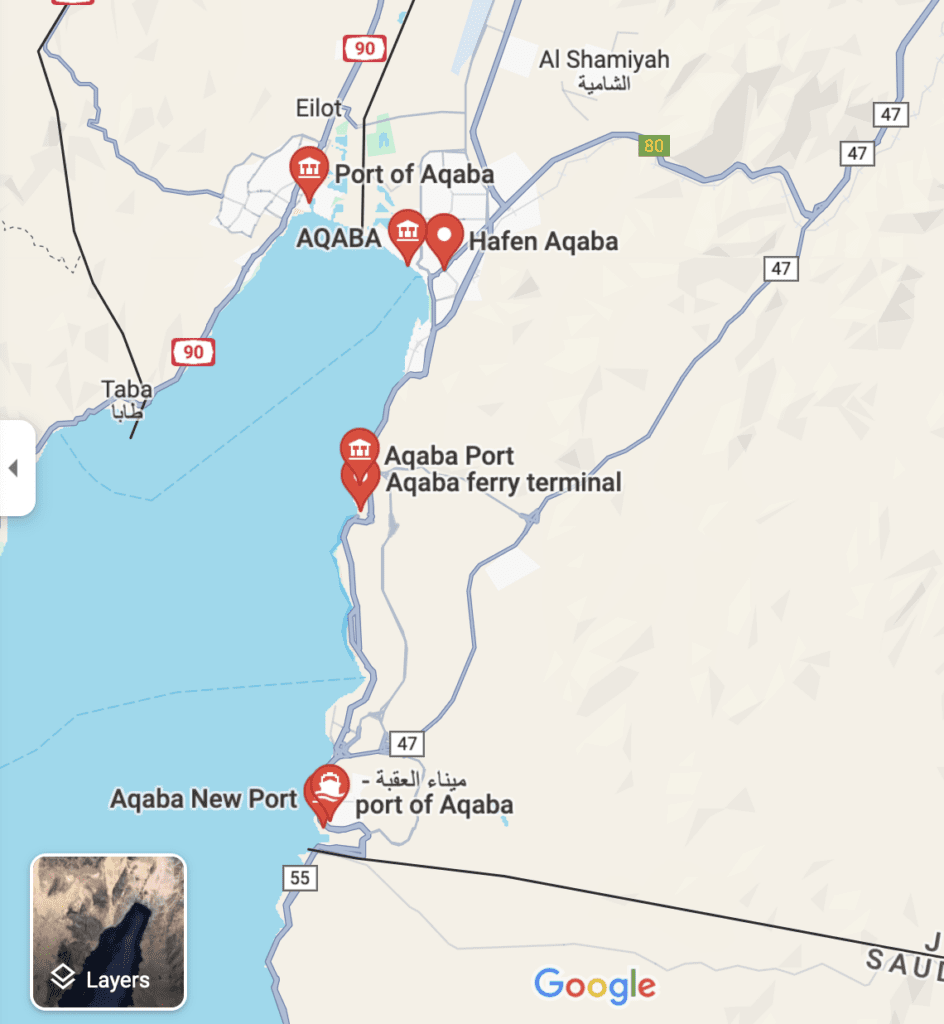

Vogel also wrote in his comments to my prior post that Potter said he started at the Port of Aqaba, which is allegedly 16 miles south of the city of Aqaba. I don’t think that’s accurate. If Potter said something about starting near a port, confusion is certainly easy here since Google Maps shows at least four and maybe five sites that can be called a “Port of Aqaba,” some being far to the south of the city itself. Going clockwise around the Red Sea, we have the Port of Aqaba shown as close to Eilot (Eilat), about 3 miles west of Aqaba, then Hafen Aqaba (Hafen is German for “port”) near downtown Aqaba, then an Aqaba Port by the ferry terminal several miles south of Aqaba, and Aqaba New Port / Port of Aqaba near Jordan’s border with Egypt, which may be the port (ports?) Vogel was thinking of. The multiple port candidates may have led to some confusion. Starting in or very near to the city of Aqaba seems to give a distance of about 75 miles an oasis in Wadi Tayyib Al Ism, a reasonable place for an encampment after three days of travel in the wilderness.

Here is a view from Google Maps at https://www.google.com/maps/search/port+aqaba/@29.4720703,34.8941159,11.36z?entry=ttu:

In Lehi in the Wilderness, Potter gives some details on pages 25-28. He speaks of the last caravan town that Lehi might have seen, Ezion-geber near modern Aqaba (p. 25), not some remote port. An initial approach near the Eilat/Aqaba area is the most reasonable one for Lehi’s journey. While the exact location of Ezion-geber may be unclear, Britannica says archaeological evidence points to a location at Aqaba (see “Ezion-geber“). In any case, it’s clear that Potter is starting near Aqaba. He speaks then of driving south and states that they went 25 miles to Haql (p. 25). There is a slight problem here, but it’s the opposite of the problem Vogel sees. Using Google Earth to measure the distance from a spot just north of Aqaba and then south to Haql, the distance is more like 18 or 19 miles, not 25. And then the distance south to the eastward turn seems off. But again, the overall distance, as recorded from his speedometer plus a little walking at the end, as I recall, makes sense.

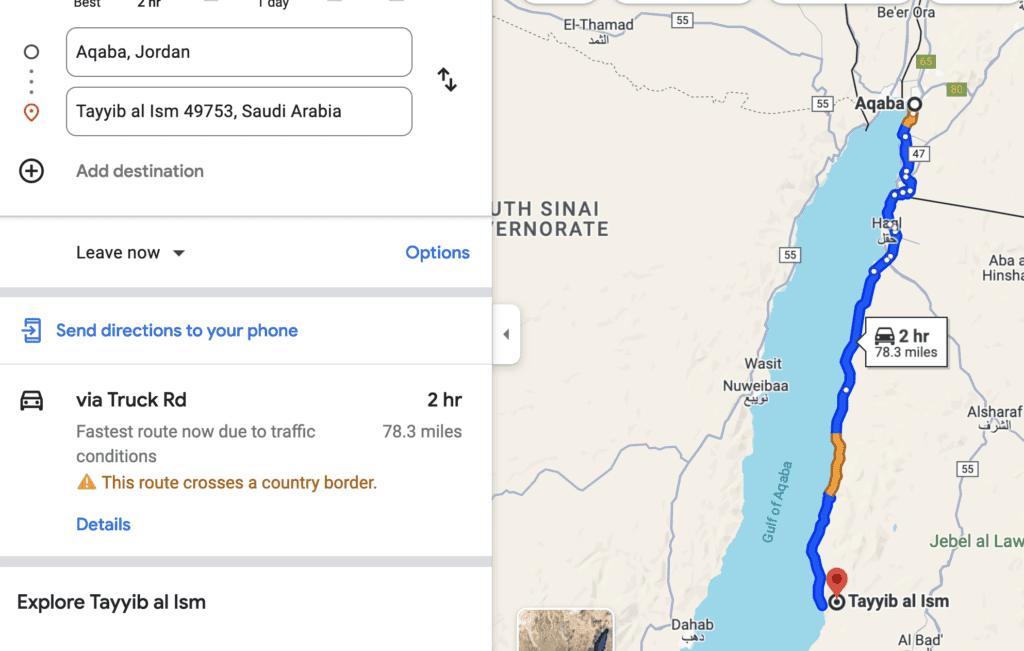

Another comment from Vogel says that my problem is using Google Earth instead of Google Maps. Google Maps can show you the distance by road, which may be best for assessing the driving route that Potter may have taken (assuming the roads have not changed much in the past 25 or so years), but not necessarily the distances a caravan would have taken. Today there is a coastal road that one can take to reach the coast adjacent Wadi Tayyib al Ism. Google Maps shows a distance of 78.3 miles. Some of that is from paths that zig-zag. But since Potter reports turning into the mountains for a distance of about 6 miles and then going south, it’s fair to assume that distance he drove may be somewhat more than 75 miles. There may be a need to redo the drive to more precisely document the proposed route that Lehi would have taken. Here is the map from Google Maps showing the coastal drive to Wadi Tayyib al Ism.

Here’s a view from Google Earth showing the oasis in Wadi Tayyib Al Ism, the likely site of Lehi’s encampment (labeled Setenta Palmera for some reason) that would have had water from the river nearby and multiple palm trees, as one can see now — possibly resembling the encampment site in Exodus 15:27, as quoted above.

Note that Wadi Tayyib al Ism is not just an ideal candidate for a continually flowing stream (“river”) that flows into the fountain of the Red Sea in the welcome shade and shelter of an impressive valley, but is also an ideal candidate for a starting point for a wonderfully feasible south-southeast journey to Shazer that can literally begin just as Nephi reports: after packing up their gear, they walk across the river and begin going south-southeast. There is a wadi directly across the River Laman candidate from the logical encampment site on the north of the stream, and an opening in the canyon wall there that one can take to reach the place Shazer (or the ideal candidate as proposed by Aston). That’s part of the explanatory power that is gained by recognizing Wadi Tayyib al Ism as a candidate that follows from seeing the borders near the Red Sea as the starting place for the symbolic three-day trek imitating Moses in leading Israel past the Red Sea to a miraculous source of water.

There are still plenty of questions and a need for more data and exploration, but it surely has to count for something that actual field work has identified a site that serves as a reasonable candidate for a Book of Mormon site that Joseph Smith could not possibly have known about, no matter what squiggles someone thinks he might have seen on a map he didn’t have access to (more on that later). The Book of Mormon essentially predicts the existence of a reasonable campsite on the north side of a river of water that flows into the Red Sea and is a three-day journey from the northern end of the Red Sea, and that prediction, once thought to be sure proof that the Book of Mormon was a fraud, now is supported by solid data with printed publications, video, photos, and even satellite imagery for all to see. That site fits the Book of Mormon information, both in terms of what is there and how one gets there, as well as where one goes next (four days to Shazer). It’s a reminder that we need to take the Book of Mormon seriously, while exercising patience when the “experts” throw out tough questions about the apparent defects or gaps in the Book of Mormon. Time and time again, what seem like major weaknesses in the Book of Mormon end up becoming strengths. Hang on and keep looking patiently when challenged, for “in your patience possess ye our soul” (Luke 21:19).

I believe I have shown you that limiting the three-day journey to the borders of the Red Sea is not a sound reading of the text. If you were to try to read it that way, it would only apply to the “borders … nearer the Red Sea,” which, if you equate with mountains, applies only to the range that begins 40 miles down the coast of Aqaba and makes no sense.

The text says the three-days of travel were in the wilderness, not borders. The previous use of “wilderness,” about Lehi traveling with his family, is general and not specific, as I have already argued. Nephi’s heading also has Lehi leaving his house in Jerusalem and traveling three days in the wilderness without any qualification. Your attempt to escape its implications makes no sense. A better apologetic might be that Nephi changed the 14-day trip into a 3-day trip to parallel the exodus better. But arguing that he focused on a particular segment of the trip doesn’t work. The use of phrasing from Exodus isn’t in dispute and doesn’t help your awkward reading of the text. You are just trying to wrestle with the plain meaning of the text.

I think you are beginning to see that Wadi Tayyib al-Ism has problems, distance from Aqaba being one of them. Potter saw it as a problem, which led him to fudge on the miles. I hear it repeatedly said that 75 miles was the upper limit of feasibility. The distance is actually about 88 miles from the top of Aqaba. Potter, Wellington, Aston, Book of Mormon Central all present the 74 miles as beginning at the top of Aqaba, which is an impossibility. The last 30 miles through the mountainous wadis would have been treacherous and dangerous in the rainy season. If Lehi set up camp at the oasis at Tayyib al-Ism when there was a river running past it, then probably there were rivers or streams running out of the other wadis into the Red Sea at Bir Marsha, hampering quick travel to Tayyib al-Ism.

“If the[y] had to travel a few miles over the “normal” limit of about 75 miles by sleeping less and traveling longer than normal on the third day, for example, I don’t think that’s a serious problem.” You also must ask yourself: Why would Lehi travel at breakneck speed? I think your theory has been stretched beyond the breaking point.

I warned you that you couldn’t use the measuring tool except for the mountains. The reason for this is because Potter’s mileage came from his vehicle’s speedometer while traveling on the roads. He didn’t travel in a straight line. If the road couldn’t be built perfectly straight, what makes you think Lehi could travel on land as the crow flies? Coming up short when measuring the distance between Aqaba and Haql should have tipped you off that using different methods of measuring doesn’t work.

Your line, before it veers off into the mountains, goes from Aqaba to Bir Marsha. Using Google maps, I got 55.2 miles to Georgios G. Shipwreck, which is a little less than Bir Marsha. However, I believe Potter turned east at Ras Suwayhil al Saghir, the farthest south Lehi could have gone, which is 57 miles. In his 1999 essay, Potter said that the mountains that impede travel along the coast are 44 miles south of Aqaba. “The most direct [route] takes a person south from Aqaba 44 miles along the coast. Here one reaches a 6,000-foot mountain range that blocks further coastwise travel.” So if you want to know which Port of Aqaba Potter referred to, just go 44 miles up from Ras Suwayhil al Saghir and see how far you get.

If Tayyib al-Ism is such a perfect match for the river Laman, why so much speculation about the reduction of water flow and the raising of the coastline through the dynamics of plate tectonics to make it fit? Finally, you blow this up with your theory that Lehi may have believed the water reaches the Red Sea through an underground fountain. All you have demonstrated is your determination to make Tayyib al-Ism fit, no matter the circumstances. This isn’t even good apologetics.

Where do you get this strange idea that there are no mountains near the Red Sea until 40 miles past Aqaba? Look at this photo of Aqaba.

Dan said: “The text says the three-days of travel were in the wilderness, not borders.” It says “And he came down by the borders near the shore of the Red Sea; and he traveled in the wilderness in the borders which are nearer the Red Sea.” In a telegraphic statement that summarizes numerous details of such a trip, it’s reasonable to say that they came down near the Red Sea, and then traveled nearer the Red Sea. What he means by borders is unclear, and whether “in the borders” refers to just the last difficult portion or the entire three-day journey could also be a subject for debate. But a three-day journey from Aqaba can get you to the River Laman.

The “wilderness” in the scriptures tends to cover that which is not inhabited, civilized territory. The wilderness can include wild mountainous regions and coastline.

Dan writes: “If Tayyib al-Ism is such a perfect match for the river Laman, why so much speculation about the reduction of water flow and the raising of the coastline through the dynamics of plate tectonics to make it fit?” There is NO SPECULATION about the Saudi Arabian government’s withdrawal of water from the region. Without that, it’s entirely reasonable that the stream would be stronger. As for plate tectonics, I don’t think that needs to be considered, but if Potter is right, then I have no complaints. The reason we discuss any of this, though, is that we recognize things might have been different in Lehi’s day, and we wish to understand what the situation was. Good theories often begin with apparent flaws that require investigation and resolution. If the flaws are fatal, the theory needs to be abandoned. Zealous nitpicking at questions and uncertainties in a textual description raise questions that may need to be considered, but when they prove to be irrelevant or easily resolved, it’s time to begin realizing that the theory may have merit.

You keep saying it’s 88 miles to Wadi Tayyob Al Ism. How do you get that? Lehi did not have to follow all the details of the coastal road. There is relatively flat land that they could travel, and then once they cut into the mountains, the pathway is not highly tortuous. My estimate of around 75 miles from Google Earth could be close to what they did.

In any case, going a little more than 25 miles per day does not involve “breakneck speed.” Humans can go that distance on foot, but it’s not easy. 20 miles is a reasonable estimate for travel by foot, 25 miles by camel. Remember, their route was a guided one. If the Lord wanted them to push a little further into the night for part of the trip, so be it. There is nothing impossible about a 75 mile journey, and even if we accept your tortuous number of 88 miles, it’s still possible. So why would they push themselves to go whatever distance it was? They weren’t making that decision, it was guided. I’d guess that the Lord saw the significance of a three-day journey in the wilderness from the Red Sea and chose to add the Exodus-like element to the Nephite exodus.

Note that the heading does not say where the three-day journey began. In getting to the River Laman camp, they took a three-day journey from the Red Sea, and the Red Sea was probably encountered after a roughly 10-day journey after leaving the land of Jerusalem.

Whether Nephi intended an allusion to Arabic “mountains” when referring to “borders” is not a critical issue. But if so, there certainly are mountains near Aqaba. In fact, when I type “Aqaba” on Google Earth, the image that comes up is an image from showing the coast with nearby mountains right behind Aqaba. No need to assume Nephi was talking about the more prominent mountain range much further to the south.

So no, there’s no reason to limit Nephi’s travel in the borders nearer the Red Sea to mountains 40 miles south.

Dan, discussing alternatives of uncertain details often entails considering either/or situations. Considering two possibilities, either of which can work, is not to blow both of them up. It’s fine for Potter to speculate about tectonic plates and changes in elevation, but I don’t think it’s needed.

There’s no speculation involved in recognizing that the stream must have been much stronger, at least at times, based on the scouring of rock that is evident.

There’s no speculation in stating that the stream previously reaches all the way to the Red Sea, for it still does in our era and I’ve provided photographic evidence of that.

But if it was still descending into the ground near the Red Sea coast in Nephi’s day, it is still possible that Lehi had that in mind in referring to the river flowing into the fountain of the Red Sea. A fountain can be a spring or a subterranean water source, as well as the water that flows out of that source. It’s just one of several possibilities worth considering. The most likely situation, IMO, is that the stream was much stronger in Lehi’s day and flowed directly into the Red Sea or maybe just a few yards short, though still light enough to walk over when they left their encampment and headed to Shazer as stated and as is clearly possible.

It’s a logical fallacy to accuse someone of blowing up their argument when they consider alternative possibilities, even when they are mutually exclusive possibilities. Life is complicated, and when there is incomplete data, sometimes mutually exclusive alternative need to be considered. It doesn’t destroy the underlying scenario being discussed.

Jeff, you have argued that the three-day journey in the wilderness mentioned in 1 Nephi 2:6 pertains to the previous mention of wilderness. I have already shown that the previous mention deals with Lehi’s traveling with his family, which refers to the total wilderness, not specific segment of the wilderness. An additional and complicating problem is created when “borders” is equated with “mountains.” It changes how 1 Nephi 2:5 is read. “And he came down by the borders [mountains] near the shore of the Red Sea; and he traveled in the wilderness in the borders [mountains] which are nearer the Red Sea …” Potter interprets the first part as pertaining to the mountains near Aqaba and the second part as referring to the mountains 40 miles down the coast. So, the previous mention of wilderness also pertains to borders “nearer” the Red Sea.

It seems to me that the border/mountain interpretation is incompatible with the three-day from Aqaba argument. I have noticed that many apologists, including Potter, Aston, even you, avoid quoting “borders … nearer the Red Sea” when making the three-day argument.

Why would Nephi refer to being near the mountains when he arrived near the Red Sea, when the probable route took them down the Arabah Valley? In fact, the mountains near Aqaba are a continuation of the range that runs down from above the Dead Sea. Besides, it appears to me that there is one mountain range, with the southern part divided by Wadi Ifal.

You have defended Potter’s equation of the Arabic Gebul (mountain) with the Hebrew Har (border). A mountain might represent a border as much as a wall or coastline could, but they are no synonyms, which is how Potter uses it. The point is that the mountains should be the outer limit of something. You don’t have two outer limits or barriers. Besides, the text doesn’t mention two borders, one near and the other nearer the Red Sea. Lehi first comes near the border, then enters the border. One border.

It doesn’t make sense for the first part of verse 5 to refer to Aqaba, and then jump 40 miles south in the next phrase without a clue. The only way to read it that way is to add to the text an interpretation based on a poor understanding of Arabic and Hebrew and wild speculation about the underlying word JS mistranslated.

A far better reading of 1 Nephi 2:5-6 is that Lehi came down near the borders of the Red Sea, then passed into the borders and traveled a short distance before setting up camp. He was near the Red Sea and then nearer the Red Sea when he entered the borders, which is an obvious reference to the seashore. Seashore, or coastline, is how “borders” should be read.

Dan wrote: “You have defended Potter’s equation of the Arabic Gebul (mountain) with the Hebrew Har (border).” No, that’s not right. In discussing Potter in my “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map, Part 1,” I said this:

But as I’ve explained, my arguments don’t rise or fall with the the possible meaning of “borders” as mountains. Non-mountainous borders work also work well. Now before you tell me that this is contradictory and destroying Potter, let me explain that I don’t know exactly what Nephi meant, and so it is reasonable to consider various plausible possibilities. That’s normal for scholarship and not “disingenuous.” It’s how we deal with uncertainty. Is an electron a wave or a particle? Don’t tell physicists that they are being disingenuous if the refuse to be nailed down to just one answer when there is uncertainty. Multiple possibilities often need to be considered. What we do know is that once an ancient caravan reached Aqaba, they could reach a remarkable candidate for the River Laman in three days. That’s pretty significant, especially given that Book of Mormon critics long maintained that there were no rivers in the area and that the whole story was impossible. So what are borders? Yes, it could be the coastline, or barriers near the cost, or mountains. As coastline, it could mean that he came near Aqaba, in view of the Red Sea, and then went nearer to the Red Sea as they went south of Aqaba. As mountains/barriers, it also works. Note that there are mountains on the east and west side of the valley coming to Eilat and Aqaba. There are 2,000 to 3,000 foot mountains a couple miles from the shore of the Red Seal all along the path going south from Aqaba. Use Google Earth and your see these mountains and get their altitude.

You originally said there are no mountains near Aqaba, but Google Earth shows that is wrong. Here’s a photo of Aqaba that might help. There are mountains near Aqaba. Now you’re trying to obfuscate by talking about distant mountains, where there is no need. There are mountains all along the way, just as there is a massive granite valley with a stream that can serve as a remarkable candidate for the “impossible” River Laman and Valley of Lemuel.

Jeff, Your subterranean-fountain theory shows you have no confidence in Potter’s speculations. I doubt your theory will be adopted by many of your fellow apologists, but it also shows you have a very low standard when it comes to responding to critics. It’s also mind-boggling that you are willing to accept that the river never flowed into the Red Sea while at the same time touting Tayyib al-Ism as a spectacular piece of evidence for BofM historicity.

Nevertheless, you think there is evidence for a larger stream at Tayyib al-Ism during Lehi’s time based on the “scouring of rock” or erosion of the floor and sides of the canyon. It seems to me that Potter, Aston, and you have not given this serious thought, because, if you did, it would occur to you that the canyon has been in existence for millions of years and subject to seasonal rains and flash flooding. So there is no justification for seeing evidence of a perennial stream in Lehi’s time.

Water from the gravity-fed spring located about three miles up the canyon doesn’t reach the Red Sea. What you see in photos appears to be runoff from the upper valley during the rainy season (Nov.-May).

Verse 8 states that “the river … emptied into the Red Sea; and the valley was in the borders near the mouth thereof.” This would suggest that the valley and Lehi’s campsite were near the seashore. Tayyib al-Ism does not empty into the Red Sea and has no mouth, and there is no evidence that it was different in Lehi’s time. Verse 9 says “the waters of the river emptied into the fountain of the Red Sea,” and that “this river” was “continually running into the fountain.” Both Potter and Aston compare this situation to Lehi’s dream, which refers to the river and fountain having depth and being more or less straight.

Not only do you cancel out Potter’s theory with your subterranean theory, but you do so disingenuously. You say your theory is “just one of several possibilities worth considering,” then state that “the most likely situation, IMO, is that the stream was much stronger in Lehi’s day and flowed directly into the Red Sea or maybe just a few yards short.” Finally, you (and other apologists) top this off with a declaration that Tayyib al-Ism fits Nephi’s description perfectly and that it’s the most amazing find. When you present one possible argument against a legitimate criticism and then give another contradictory possibility to another criticism, that’s being polemical. It’s like nailing Jell-o to the wall.

Dan said, “It’s also mind-boggling that you are willing to accept that the river never flowed into the Red Sea while at the same time touting Tayyib al-Ism as a spectacular piece of evidence for BofM historicity.” I never said that it doesn’t flow into Red Sea. In fact, I have expressly said the opposite. I have noted that the river likely had higher water flow anciently, even recently before the Saudi Arabian government began withdrawing significant amounts of water from the aquifer that apparently feeds the stream. So it’s safe to say that the water flow was stronger in the past. We already know that during wet times today, the river does flow all the way to the Red Sea. However, in the spirit of considering various possibilities, I have pointed out that if the water descended into the rocks near the Red Sea, it would be natural to recognize that that the stream is still flowing into the Red Sea. In that case, the “mouth” of the stream could be the place where it joins the subterranean fountain that feed the Red Sea there. So if the stream still sank into rocks anciently, probably much closer to the Red Sea than where it sinks now, one could still speak of it flowing into the Red Sea or the “fountain” thereof. But I think it’s more likely that they saw the stream doing what still does during parts of the year, flowing all he way into the Red Sea. Again, considering two alternate possibilities is not to contradict either one and is a natural thing to do when we don’t have precise information about what they saw and what they mean in describing this stream.

Dan also said, “So there is no justification for seeing evidence of a perennial stream in Lehi’s time.” Dan, surely you have noted that the stream is perennial today, even after much water has been withdrawn from its aquifer. If it’s perennial today, why could it not be perennial in Nephi’s day? Of course, there’s another possibility to consider. Lehi’s “continually running” statement does not necessarily require surveillance of the stream over wet and dry periods in the year to determine that it was really perennial. It could have just looked like a steady stream not dependent on a recent rainstorm. The oasis and other plant growth near and along the stream could have indicated that the water supply is steady. The fact that it is perennial is a nice touch, and since Nephi recorded those words on the plates long after they had spent many days there, his knowledge that the stream was perennial may have made that phrase from Lehi a particularly apt statement to select from a much longer speech.

Dan also said: “Water from the gravity-fed spring located about three miles up the canyon doesn’t reach the Red Sea.” You make that statement with surprising confidence. Is there a hydrology survey of the stream you are referring to, or did some hydrologist just offer an opinion on this without considering the physical geography? I’m curious about your source for such a sweeping statement. While the stream starts at three miles away, it comes much closer to the Red Sea before it sinks.

The stream even today can reach the Red Sea directly during the wet season. How do you know Lehi’s statement wasn’t made when the stream had a stronger source of water than we have now with water being pumped away?

Currently, the stream is said to descend into rocks about 3/8 of a mile away from the shore of the Red Sea. Potter and Wellington, in Lehi in the Wilderness, observe that “the river flows under a gravel bed for the last three-eights of a mile as it approaches the Gulf of Aqaba.” Of course water flowing from a higher elevation can sink into the ground near a shoreline and enter an ocean or lake. It’s a very common phenomenon. See Matthew A. Charette and Ann E. Mulligan, “Water Flowing Underground: New Techniques Reveal the Importance of Groundwater Seeping into the Sea,” Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, December 10, 2004. With higher water flows in Lehi’s time, it may have flowed all the way into the Red Sea all the time, or stopped short by some distance less than the current three-eights of a mile. What if the place where the stream sunk into gravel were 20 yards away from the shore, for example? Or 100, 200, or 300 yards? Is it really unlikely that in such a scenario, observers would not deduce that it was entering the Red Sea?

In some bodies of water, I have seen springs of water rising up beneath the water level of the body in question. I have both seen and felt such underwater springs. Subterranean springs may be easily noticed. Perhaps at low tide, Nephi or others may have noticed the entry of fresh water from such a spring, a “fountain of the Red Sea” obviously being fed by the stream the sank into gravel near the shore. Again, there are various possibilities to consider. But your blanket statement that water “three miles up the canyon doesn’t reach the Red Sea” seems to need some explanation. It appears to be another assertion without adequate support.

“This would suggest that the valley and Lehi’s campsite were near the seashore.” No, the text does not say that they camped at the shore. Observing the stream at or near the shore tells us nothing about where they set up their tents. It’s another unjustified assumption.

“Tayyib al-Ism does not empty into the Red Sea and has no mouth, and there is no evidence that it was different in Lehi’s time.” Potter shows a photograph of a pumping station withdrawing water from the aquifer. This is a common problem wherever water is scare: humans withdraw water that otherwise would keep flowing into the sea, having a harmful impact on ancient ecosystems. This is the story of the Colorado River, for which there is abundant evidence that much water has been withdrawn. The withdrawing of water from the source of the River Laman certainly means that its current flow is likely to be less than in the past. What do you require before you can accept something fairly obvious as evidence? And doesn’t the behavior of the stream during the wet season, flowing into the Red Sea, at least count as tentative evidence that ancient travelers arriving in the wet season could have seen a similar phenomenon? Or arriving at any time could have seen a stronger stream that we have today? I am puzzled about why you can’t see either of these issues (the withdrawal of water and the seasonal variability) as evidence that the River of Laman in Lehi’s day may have fit the details the text provides.

Your last paragraph is really puzzling. Dan, considering several possibilities is not a contradictory act. Almost every passage of scripture leaves questions about what was meant. Bible scholars routinely need to consider alternate readings, alternate manuscripts, and alternate possibilities about what was being said. Considering mutually exclusive possibilities is not contradictory. For example, where was Mt. Sinai? There are several mutually exclusive possibilities. Considering them and their implications for the text does not destroy the story.

You argue that my consideration of the (perhaps slightly) underground flow of the stream today destroys Potter’s theory about a different elevation of the landmass. No, it does not. If he’s right, then his theory would seem to work. But I’m not convinced that we have evidence for such a thing and prefer to consider less dramatic possibilities. In my view, the text can fit the geography and hydrology of the River Laman flowing into the Sea whether they saw it flowing directly into the Red Sea, or saw it flowing into a “mouth” feeding the Red Sea beneath the gravel near the shore. Both of these possibilities work. Why is that “disingenuous”? Why is that “polemical”?

Fun to see the big smart boys still straining at gnats after all these years. It’s very entertaining! Rank and file Mormons don’t care or think about any of this stuff. It’s laughable that anyone would try to defend this obvious work of fiction.

Just as “rank and file” anti-Mormons avoid engaging with the difficult questions for them to answer about the miracle of the Book of Mormon and instead use blanket statements and false bravado instead. It’s laughable that you feel the need defend yourself from an attack nobody is threatening you with.

Faith is the acceptance of a proposition without reliance on empirical evidence, distinct from the concept of Belief Perseverance, which entails maintaining a belief despite contradicting evidence. In the context at hand, what we observe is a manifestation of Belief Perseverance regarding the historical authenticity of the Book of Mormon.

Impressive. No retort was possible.

Not really

Or perhaps, given the context at hand, we observe a manifestation of your belief perseverance regarding the lack of historical authenticity, and this article hurts your feelings. I guess it all comes down to whether the Book of Mormon is all it claims to be. And we find ourselves once again using generalities that don’t advance any useful discussion. I don’t agree with Dan but at least he’s specific.

Or perhaps, given the context at hand, we observe a manifestation of belief perseverance regarding lack of historical authenticity, and this article hurt your feelings. I guess it all comes down to whether or not the Book of Mormon is all it claims to be (and whether you admit it or not, there is indeed evidence in the affirmative direction). So once again, we find ourselves using generalities that don’t advance any sort of useful discussion. I don’t agree with Vogel, but at least he has specifics to challenge.

Reviewing the posts, Lindsay seems to uncover lesser-known critiques and exaggerates them dramatically, essentially fabricating mythical challenges for himself to overcome. He will transform a solitary, unpolished critic into formidable critics (plural). When questioned about his methodology of “connection” creation, he feigns ignorance and presents what is ostensibly his dragon-slaying narrative. In essence, his entire approach is fundamentally deceptive, possibly self-deceptive.

That sounds pretty dramatic. Could you explain a little more what you are talking about? What lesser-known critiques are you speaking of and how have they been exaggerated dramatically? Always helpful to have some details, preferably factual, to help people understand an argument

Interesting picture there. How about this, you tend equivocate about the whole Arabian peninsula thing. Sometimes you suggest it is evidence (plausibility), but then say it is not evidence of historicity, but rather you are just debunking somebody else with plausibility. Apparently somebody said traveling through Arabia is impossible therefore the Book of Mormon is false? The effort you put into this seems to be much more than just debunking some loons nobody cares about.

I genuinely believe Smith did know about Islam until he was compared to Mohammed. But it seems implausible that he didn’t know that Arabia was full of dunes, but some people managed to survive there.

Are you constructing some sort of evidence of something? Wadis, a burial site, a coastal oasis all highly specific references to something? Or demonstrating what is already known, some incredible stories might be highly unlikely, but plausible, as if anyone doubt that.

Talk about what the text actual says, I just learn Mosiah 3:2 falsely says the firstlings are burnt offerings, when according to the law of Moses they food offerings not burnt offerings.

You mean Mosiah 2:3. But how do you know that the description there is false? Yes, it is true that the Old Testament does not identify firstlings as the object of burnt offerings. Based on the Hebrew Bible, they were used for sacrifices, while other animals were used for burnt offerings. But how do you know the statement in Mosiah 2:3 is false? It requires several assumptions:

1. You assume that the practices we see in the Torah could not have evolved after five centuries of being away from Israel in the New World. Must we assume that the Nephites, if a real people descended from Israelitees who left Jerusalem in 600 BC, would have rigorously followed the same practices we see described in our version of the Old Testament? I find that a reasonable assumption, but can it be made with 100% certainty?

2. You treat the lack of evidence for burnt offerings with firstlings as evidence that it was contrary to the Torah. Is that reasonable? Is there any fundamental reason why faithful Jews could not choose to include a firstling in a burnt offering rather than only non-firstlings? In other words, even if the use of firstlings for sacrifices other than burnt offerings was the standard practice in ancient Israel, is there a fundamental reason why that practice could not have evolved over the centuries?

3. You assume that the phrase “sacrifices and burnt offerings” means that the previously mentioned “firstling” were offered in both “sacrifices” (which is appropriate for firstlings) AND “burnt offerings.” That’s not an unreasonable reading, but it’s also possible that other animals were used for the “burnt offerings” that were not specifically mentioned, and it’s also possible that the term “sacrifices and burnt offerings” is a “merism” in which a part or parts of a concept are used to describe the whole. This has been discussed with respect to this verse in the article “Why did the Nephites Sacrifice the Firstlings of Their Flocks?” at Book of Mormon Central, https://bookofmormoncentral.org/qa/why-did-the-nephites-sacrifice-the-firstlings-of-their-flocks. Please consider that article.

So whether Nephite practices had evolved to include firstlings for a new class of sacrifice, or whether the phrase “sacrifices and burnt offerings” referred to the system of sacrifices in general, or whether the use of other animals for the burnt offerings was involved but not explicitly mentioned, perhaps viewed as an unnecessary details by the author or editor of the text, the language in the Book of Mormon does not force us to conclude that Mosiah 2:3 could not possibly be true and represents a false statement disproving the Book of Mormon. At worse it represents ambiguous description of a minute detail.

Wow, that was pretty amazing confession. Admitting that Mosiah 2:3 doesn’t follow the Law of Moses and it is reasonable to think it is contradiction read exactly as it is quoted . I impress with that much honesty, especially coming from Jeff. The only thing he was dishonest about was the who is making the assumption. The only ones making assumptions are those wishing to invoke eisegesis to read the quote differently.

Jeff, I will respond to all your posts dated 30 Jan. 2024.

The mountains that Potter calls the borders “nearer” the Red Sea start 40 miles south from Aqaba. Verse 5 says Lehi “traveled in the wilderness in the borders which are nearer the Red Sea.” So, did he travel in the mountains 40 miles south of Aqaba for three days? See how equating borders with mountains conflicts with the claim that it was a three-day journey from Aqaba to Tayyib al-Ism?

Potter uses the word “mountains” as a synonym for borders, which it isn’t. Why would Nephi say they “came down by the mountains near the shore of the Red Sea,” when the same mountains extend up into Israel?

Actually, there are not two borders in the text, nor are there two mountain ranges. There is only one border. Lehi comes near the borders of the Red Sea and then enters the borders nearer the Red Sea. This obviously refers to Lehi traveling down the coast. Potter’s reading has Lehi pass by the mountains near the Red Sea and then in the next sentence, he jumps 40 miles down the coast, where he enters the mountains. This is a very clumsy reading of the text, which is driven by an equally clumsy equation of borders with mountains.

There is no evidence for a significant river existing at Tayyib al-Ism. No evidence that a lowering of the ground water from pumping has significantly reduced the output of the natural stream in the canyon—only speculation. Potter and Aston have only referred to the erosion on the floor and walls of the canyon as evidence for a larger stream, but that can be explained by the seasonal rains and flash floods that have occurred there for millions of years.

The water you see coming out of Tayyib al-Ism in some photos is not from the aquifer, but from runoff from recent rain coming mostly from the upper valley. Sometimes, this creates flash floods. You don’t think the video of the flash flood raging out of Tayyib al-Ism is from the aquifer, right? Seeing that should give you an idea of how the smoothing of the floor and sides of the canyon occurred.

Apologists are fond of saying the stream runs year around and empties into the Red Sea, knowing that it doesn’t empty into the Red Sea year around. They leave the unwary listener, even some fellow apologists, thinking that the stream runs and empties into the Red Sea year around. But it doesn’t, and we don’t know that it ever did.

On the location of Lehi’s campsite: the text says the valley was near the mouth of the river and that Lehi’s camp was in the valley. Now that Aston locates Lehi’s camp at the oasis in the larger upper valley, which goes on for at least twelve miles, how can one say the valley is near the mouth of the river?

You only think that questions about Potter’s and Aston’s theories are “easily resolved”; that’s because you have a very low bar for what you count as answers. Jeffery Chadwick raised questions long ago, and Potter and Aston have tried to answer them, but I’m saying their answers have been inadequate.

Besides simply measuring it as accurately as possible, there are several ways to get to 88 miles from Aqaba to Tayyib al-Ism. The easiest is by simply adding 16 miles (for the distance from the top of the gulf to Port Aqaba) to Potter’s total of 72 miles. Another way is to take Potter’s 44 miles down the coast to the Bir Marsha area, add 16 miles, and then 28 miles through the wadies to Tayyib al-Ism. If you think Lehi camped near the mouth of the canyon, you should add another 3-4 miles.

Jeff says: “going a little more than 25 miles per day does not involve “breakneck speed.” Humans can go that distance on foot, but it’s not easy.” I’m going by what Potter, Wellington, and Aston have said. The apologists have set 75 miles as the maximum distance Lehi could travel in three days, not me. I would set it much lower.

Lehi’s route wasn’t “guided,” because they didn’t have the Liahona yet. If they were already guided by some means, why would they need that instrument? So, you think the Lord pushed them to travel as fast as they could to have a significant parallel to the exodus? This is an ad hoc theory on your part. The only reason to push hard to get to Tayyib al-Ism is to fulfill the apologists’ need for evidence.

You say, “the heading does not say where the three-day journey began.” It was “in the wilderness,” so it began just outside the “land of Jerusalem,” not outside “the land of Judah,” like Hamblin tried to argue. Either way, it’s more than a three-day trip.

Do you really think that what happens at the subatomic quantum level allows you to devise contradictory and incoherent arguments? You are not simply formulating theories to explain the Book of Mormon, you are devising apologia to establish the book as an authentically ancient text. You are presenting Tayyib al-Ism as evidence, something Joseph Smith could not have known. The expectations for that kind of exchange are different.

You did not offer your subterranean-fountain theory “in the spirit of considering various possibilities.” You gave it to counter RT’s criticism, to confuse the situation, and not to carry the investigation forward.