A couple of recent blog posts from skeptics have once again announced that Nahom in the Arabian Peninsula, the alleged soul shred of evidence for the Book of Mormon, the last hope for die-hard believers and apologists, has been carefully examined and found to be completely unworthy of our attention. It is insignificant, irrelevant, and not we believers have simply been wasting our time and embarrassing ourselves with unjustified excitement. Shame on us.

A couple of recent blog posts from skeptics have once again announced that Nahom in the Arabian Peninsula, the alleged soul shred of evidence for the Book of Mormon, the last hope for die-hard believers and apologists, has been carefully examined and found to be completely unworthy of our attention. It is insignificant, irrelevant, and not we believers have simply been wasting our time and embarrassing ourselves with unjustified excitement. Shame on us.

The blogs I’m primarily considering are both at Patheos.com, home of many excellent religious discussions. The first comes from a professor of history, Philip Jenkins, in a post titled “The Nahom Follies.” While his tone may be a little too strident and far too sarcastic, he makes some points that deserve a response, even though I am pained at how much he misses in his critique. But these are the kind of mistakes that many people make who are trying to be reasonable, responding to what they think they know or have heard. His Nahom follies are the follies of many other good people as they briefly look our way, or even as they try to genuinely investigate Mormonism, so I think it is important to consider what he says and understand where the problems are in his approach.

The primary problem, in my view, is that he treats the entire corpus of Book of Mormon evidence as if it were little more than one tiny speck on a map of Arabia, a solitary fruit fly of faith that he handily splatters with with one wave of swift wit. Volumes of scholarship such as the works of John Sorenson, the publications of the Maxwell Institute, the growing work of the Mormon Interpreter, and many others dealing with the intricate details and evidences related to the Book of Mormon, in the end all mean nothing. He’s been exposed to some of that, I suspect, through his interactions with other LDS people like William Hamblin at Patheos, but somehow what he’s managed to digest from LDS apologists (or perhaps from the non-LDS caricatures of LDS apologists) is that we’ve got one precious little data point that we cling to with all our might. When it comes to evidence, all Mormons have going for them is the word Nahom, or actually just 3 letters from Nahom, the letters NHM, that were miraculously (please apply an exasperated sarcastic tone to that word) found somewhere in an incredibly large portion of the world with zillions of place names, one of which happens to sort of sound like an actual name (gasp!) in the Book of Mormon, if you pronounce it just so. I cannot do justice with a paraphrase, so I will quote what the good professor writes about the archaeological evidence related to Nahom:

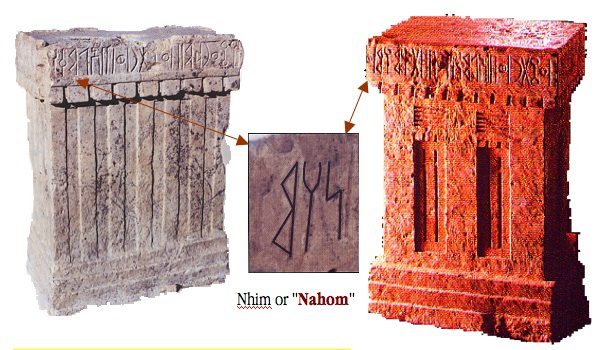

Supposedly, this is a site where Lehi stopped in the general area of Arabia, “the place which was called Nahom,” and in modern times, a related name with a NHM-stem has been found inscribed on some altars discovered in the region, in modern Yemen. The Book therefore (seemingly) reports something that Joseph Smith could not have known in 1830! Meridian Magazine breathlessly reports “Finding the First Verifiable Book of Mormon Site.” This is, literally, the only case where anyone still seriously pretends that they have some kind of archaeological support for the Book of Mormon, though they should be embarrassed to do so….

Apologists argue that it is remarkable that they have found a NHM inscription – in exactly the (inconceivably vast) area suggested by the Book of Mormon. What are the odds!

By the way, the Arabian Peninsular covers well over a million square miles.

Yes indeed, what are the odds? Actually, that last question can and must be answered before any significance can be accorded to this find. When you look at all the possible permutations of NHM – as the name of a person, place, city or tribe – how common was that element in inscriptions and texts in the Middle East in the long span of ancient history? As we have seen, apologists are using rock bottom evidentiary standards to claim significance – hey, it’s the name of a tribe rather than a place, so what?

How unusual or commonplace was NHM as a name element in inscriptions? In modern terms, was it equivalent to “Steve” or to “Benedict Cumberbatch”?

So were there five such NHM inscriptions in the region in this period? A thousand? Ten thousand? And that question is answerable, because we have so many databases of inscriptions and local texts, which are open to scholars. We would need figures that are precise, and not impressionistic. You might conceivably find, in fact, that between 1000 BC and 500 AD, NHM inscriptions occur every five miles in the Arabian peninsular, not to mention being scattered over Iraq and Syria, so that finding one in this particular place is random chance. Or else, the one that has attracted so much attention really is the only one in the whole region. I have no idea. But until someone actually goes out and does some quantitative analysis on this, you can say precisely nothing about how probable or not such a supposed correlation is.

And to make an obvious point once more: the burden of proof on this – and the chore of crunching the numbers – belongs to the people making the claims. Nobody has an obligation to disprove anything.

Sigh. This is a smart man, a passionate man, who in interested in LDS topics enough to write this post, but I’m afraid that he’s missing way too much here. Given the tone, I’m not sure if he will care what I have to say, but maybe people who make similar criticisms might be willing to consider a response, and I think it’s important we explain that there is a serious response that merits reconsideration. So here’s my attempt.

First, thank you for noticing the Nahom issue. It is important to us, but not nearly as important as you suggest. It is a small but meaningful part of a great deal of evidence related to Book of Mormon plausibility, and a significant part, only part, of the evidence specific to the Arabian Peninsula.

As I see it, the significance of Nahom or NHM is not that someone found those letters somewhere, anywhere, in the vastness of the Middle East, but that it was found at precisely the place the Book of Mormon calls for. Within a few miles, anyway, of the region where one can turn away from the general south-southwest direction of travel coming down from Jerusalem, apparently along the ancient incense trail, and then turn east to reach the eastern coast of Arabia. And then, just as the Book of Mormon says, nearly due east of Nahom is the surprising recent find of an excellent candidate for Bountiful. It’s pretty impressive evidence (not proof) that helps support the case for authenticity in at least part of First Nephi, but critics have been rather consistent in reducing it all to a minor blip or two that they can overlook or squash with one deft blow.

I’ll further review the significance of the finding of evidence for Nahom in a moment, but I’ll first point out that one of the most important contributors to the extensive Book of Mormon evidence from the Arabian Peninsula, Warren Aston, has explained in his important book, In The Footsteps of Lehi, that Arabic names based on NHM appear to be rare. He writes that “the name NHM (in any of its variant spellings, Nehem/Nihm/Nahm, and so on) is not found anywhere else in Arabia as a place name. It is unique.” (p. 12) That point has been made several times. You can go search on any of the maps available for Saudi Arabia and try finding other NHM names yourself outside of the region some of us are excited about. NHM names certainly don’t occur all over the place. The Nihm tribe appears to have been in much the same area for a very long time, and now we have archaeological evidence that they were around and using that name in Lehi’s day. You can wonder if the place name associated with NHM was still a place name in Lehi’s day as it has been in recent centuries, but it’s plausible that it was, in my opinion.

It’s not just Warren Aston that has looked for other examples of NHM names in the Arabian world. I took a look myself, searching over Wikipedia’s list of Arabic place names and a few parts of some maps (you can see the most detail on some of the high-end European maps of Arabia that James Gee has studied and compiled for the Maxwell Institute–the PDF file is over 100 Mb). Nothing else seems to be close, as far as I can tell. Look for yourself. More significantly, Chris Johnson, a former Mormon quite anxious to trash the Book of Mormon with the power of Big Data, made a seemingly powerful case against the significance of NHM as a unique place in a presentation a couple years ago. As I discussed in my initial response at Mormanity, by applying his sophisticated search engine skills to come up with a big list of NHM names from all over the world to argue that there is nothing special about place names with the letters NHM. In fact, he even quipped that it looked like NHM names were some of the most common place names– just look at the list and you’ll see some common names for yourself: Enham, um, and so forth. In response, I pointed out that NHM names from North America, Europe, or southern Africa tell us nothing about the significance of finding Nahom where it is supposed to be in a specific part of the Arabian Peninsula–it’s an absurdly irrelevant argument. But even if we accept the argument that NHM place names on maps anywhere are relevant because they could have been inspiration for Joseph’s fabrication of Nahom as a place name, there is a problem with the abundant list of names that Johnson found as he scoured the globe for NHM places: many of them, in fact, just about all of them, were not available for Joseph to swipe in 1829, or are so minor, remote, and insignificant that he probably had no chance of encountering them. See the details in one of my favorite posts at Mormanity, “Noham, That’s Not History.”

Getting back to the significance of the attack on Nahom, I’ll now summarize the story of evidence from the Arabian Peninsula, something I discuss in more detail on my Book of Mormon Evidences page (and elsewhere here and at the Nauvoo Times). The Book of Mormon in First Nephi 16-17 in just a few verses tells us about an 8-year experience from the time that Nephi and his family left Jerusalem to the time they set sail from somewhere on the eastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, though there is no explicit mention of the name Arabia or virtually any other detail that would be readily recognized by modern readers. But in spite of the sparse description, the fascinating thing is that enough specific details are given that we can actually attempt to recreate the path they took. We learn that about 3 days into their trip, they encountered a dramatic valley with “river of water” flowing continuously into the Red Sea. They named the valley after Lemuel and the river after Laman. Departing from this region near the Red Sea, they then continued south-southwest — a rather precise direction. Along the way, they would pass through some fertile regions, but also endure hardship and even death. The father of the daughters Lehi’s sons had married, Ishmael, passes away, and he is then buried at a place called Nahom. They didn’t give it that name, but report that it “was called Nahom.” After his burial and some mourning and murmuring, the family changes course, being led by a miraculous compass-like director called the Liahona, and then they begin a journey going nearly due east. This becomes a very difficult part of the journey, but they survey and reach a marvelous destination on the coast that they name Bountiful. Life is much better there at this fertile, pleasant place, but eventually they must leave after Nephi constructs a ship from the wood and ore he finds in the area, and they set sail for the New World.

For those who argue that Joseph Smith just drew from his environment to create the Book of Mormon, the trek across the Arabian Peninsula raises interesting questions. Why attempt writing about something so completely foreign with so many unknowns that later readers might investigate? Where to even begin? If it were me crafting the story, I’d just have them stroll over to the nearest port on the Mediterranean coast and hire some Phoenicians for a three-hour cruise or something. But this is scripture, the kind where the Lord gets involved and uses journeys not to get us somewhere quickly and comfortably but for all sorts of teaching and growing experiences that tend to take a lot of time and patience. Scholars may holler, but those who have experienced journeys of faith might recognize that the long preparatory trial of Nephi’s journey is much more consistent with the Lord’s strange ways of bringing us home.

What has become greatly interesting to some LDS people in the past few decades is the growing body of evidence, even gritty, tangible evidence dug from the sand, pointing to the plausibility of the account in First Nephi 16-17 as an authentic ancient record, the kind of record describing the kind of sacred, challenging journey that might have been made by an ancient Israelite who actually traveled through the Arabian Peninsula and encountered the kinds of places recorded in First Nephi. Instead of becoming exponentially more ridiculous as the Western world has learned ever more about Arabia, the account in the Book of Mormon has become increasingly plausible and interesting, to the point of even having genuine archaeological finds like 7th-century BC altars from Marib, Yemen with the tribal name “Nihm” on them, adding to the plausibility of the account, in addition to having “direct hits” come from on-the-ground field work exploring the geography, geology, and other aspects of key sites like Wadi Sayq in Oman.

The evidence includes the work of George Potter who provides intricate documentation for excellent candidates for the River Laman and the Valley Lemuel, at a location that suits the text and with features that add new understanding to the comments in the text. His book Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New Documented Evidences That the Book of Mormon Is a True History should be required reading for evaluating this remarkable site.

Here is a summary from J. Cooper Johnson, “Arabia and The Book of Mormon” at FAIRMormon.org as he reviews a presentation from Dr. S. Kent Brown:

Potter, along with the other researchers, have successfully identified this valley as the only one in this area of Arabia to have a running stream of water, a prospect which was not likely in such an arid area of the world. However, it was finally found. It did exist, although Joseph Smith, or anyone else in his part of the world, could not have known about it. Traveling To Nahom Nephi records that his family left the first camp and traveled “south-southeast” and continued in that direction until they arrived at “the place which was called Nahom” (1 Nephi 16:13, 34). Brother Brown, referring to Nephi’s choice of words, notes that, “the expression is passive, meaning that someone else had named the place. At all the other stops which are named in Nephi’s narrative, it was family members who named the places. But when they reach Nahom, it was a place that already enjoyed a preexisting name.” So, one should expect, at some point, this place called Nahom to be identified on some ancient document or artifact, if it was indeed a preexisting location and known well enough for Lehi and his family to identify it by it’s name, once they arrived.

Back in the 1970s, Ross Christensen and Warren and Michaela Aston estimated the location of Nephi’s Nahom to be in modern-day Yemen and started doing their research, which eventually yielded some fruit. The Astons “found that this name, or its equivalent which is spelled Nihm, also appeared in Arabic sources which go back to the early Islamic period, the ninth century A.D.” and “is known as both a place name and as a tribal name,” according to Brother Brown.

This was a substantial step in identifying the location of Nahom. For, as Brother Brown notes, “this area lies almost due west of the place where Bountiful must have lain in Oman.” This is important, because Nephi recorded turning “eastward” out of Nahom and eventually ending up in the place they called Bountiful, which we will discuss in greater detail shortly. However, as Brother Brown points out, “There was a problem.” While the Astons found a location with the same name, it could only be confirmed back to the Ninth century A.D., and Nephi’s reference occurs roughly 1500 years earlier.

As Brother Brown mentioned, “we needed a written source that would establish this name closer to the time of Lehi and Sariah,” which didn’t exist at the time. However, “now we have the evidence.” Brother Brown describes his discovery as follows:

I became interested in an exhibit of ancient Yemen artifacts that was in Paris about four years ago. I saw a notice of it in a magazine. The exhibit is still showing in Europe under the title of the Queen of Sheba. I bought the catalogue. I was interested in some incense altars that were donated to a temple in south Arabia. These altars are inscribed with the name of the donor, the father’s name, and the grandfather’s name, as well as the tribal name. At first, I was less interested in the names than in the shapes of the altars because these altars seem to preserve distinctive architectural forms that distinguish early Arabian sacred buildings… While I was examining the inscription of one of the altars that is pictured in the catalogue of this exhibit, I read the name of the donor: ‘Bicathar, son of Saw_d, son of Nawc_n, tribe of Nihm.’ Moreover, the excavator who translated the inscription dates this altar to the seventh-sixth centuries B.C. I thought, Bingo!

So, Brother Brown had now found an ancient Arabian artifact with the name Nihm, or Nahom that could be dated back to the time of Lehi.

Some may wonder why the name Nihm is being likened unto Nahom. Of course, they are different. However, Brother Brown makes an important point when he informed us, “in Semitic languages one writes with consonants rather than vowels. Hence, the name is NHM. These letters make up the name on the altars and also the name Nahom.” One difference is worthy of note, when considering how NHM would have been pronounced, which determines how we add vowels to the word in English. The south Arabian NHM would have been said with a soft “H” sound, thus rendering it “Nihm.” However, the “H” in Hebrew, would likely have been a strong “H” sound, the Hebrew letter, “het,” resulting in “Nahom.” Additionally, Lehi and his family would have associated NHM with “a Hebrew term which was familiar to them, that is, Nahom.”

One last note on the subject of Nahom. As mentioned earlier, Nephi recorded that after traveling south-southeast and arriving at Nahom, “from that time we did travel nearly eastward” (1 Nephi 17:1). This is significant because, according to Brother Brown, “in the region of Nahom in South Arabia, all roads turn east,” toward the incense capital of Southern Arabia, Shabwah. And once again, this information was not available to Joseph Smith.

Every bit as significant a find as Nahom, while not addressed at length in Brother Brown’s presentation, is the discovery of a place on it’s south-eastern corner that matches, in every aspect, the place Nephi called “Bountiful.” In the country of Oman one finds a stretch of beautiful land with all manner of vegetation, in contrast to the rest of Arabia, which is dry desert land. This area becomes “a Garden of Eden” during the “summer monsoon months” and “even in the dry season…plants are still blooming and fruit is ripening,” according to Brother Brown.

And, of course, you might have guessed, since it matches Nephi’s description of Bountiful (see 1 Nephi 17:5: 18:1), it is also found right where Nephi describes it, eastward from Nahom.

Regarding the significance of Nahom, also see Neal Rappleye and Stephen O. Smoot, “Book of Mormon Minimalists and the NHM Inscriptions: A Response to Dan Vogel,” Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture, 8 (2014): 157-185. After responding to a series of objections about Nahom, including an excellent discussion of the differences in the Hebrew NHM and the South Arabian NHM and the plausibility of the Book of Mormon’s word play on Nahom, the authors then give this summary of correspondences between the Arabian Peninsual NHM and the Nahom of the Book of Mormon, and why it’s not enough to just say Joseph got that word from the Bible:

Both Nahom in the Book of Mormon and Nihm in Southern Arabia match in the following interlocking details:

- Both are places with a Semitic name based on the tri-consonantal root nhm.

- Both pre-date 600 bce (implied in 1 Nephi 16:34).

- Both are places for the burial of the dead (1 Nephi 16:34).

- Both are at the southern end of a travel route moving south-southeast (1 Nephi 16:13–14, 33), which subsequently turns toward the east from that point (1 Nephi 17:1).

- Both have “bountiful” lands, consistent in 12 particular details, approximately east of its location (1 Nephi 17:4).

While the presence of similar names in the Bible might be able to explain the first of these correlations, it simply cannot account for the all the ways the two places correspond. As Daniel C. Peterson once commented, “nhm isn’t just a name. It is a name and a date and a place and a turn in the ancient frankincense trail and a specific relationship to another location.” Suggesting that Joseph Smith simply got the name Nahom from the Bible is an insufficient explanation of the correlation. [emphasis mine]

There is much more to be said, especially of Bountiful, where Warren Aston has shown with extensive detail and beautiful photographs how the candidate Wadi Sayq, nearly due east from Nahom, meets over a dozen criteria that one can extract from the text. To that list can now be added the rare presence of iron ore that could have been used by Nephi to make tools, now that geologists have found a significant and very unusual (for Arabia) outcropping or iron ore at the site proposed as Bountiful.

Collectively, this body of evidence demands to be taken seriously. And it’s far more than just three random letters that someone found anywhere in the world or in any random place and time in Arabia.

Critics, however, have tended to treat the evidence as if it were little more than claiming to have found a place name Nahom in Arabia, a claim that they can attack on several grounds. The easiest ground, of course, is that the name of the tribe is Nihm, not Nahom, and is a tribal name, not a place name, among other complaints. They can also say that Nihm or Nehem or Nehhm is not the same as Nahom. And they can say that the huge concentration of graves marked as an ancient burial place called Nehhem on a map from the University of Sana’a is actually 25 miles north of Wadi Nahm/Nahom, which is also a few dozen miles away from Marib where the ancient altars from Lehi’s day with the Nihm names on them where found, so all of those interesting correspondences to the Book of Mormon text aren’t precisely in the same location, but more like associated in a general area that may not all have been called “Nahom” at that time. Yes, life is complicated, but those complexities are things that we can deal with. They hardly invalidate the premise that we have found remarkable evidence for the plausibility of the Book of Mormon, a broad body of evidence that involves Nahom/Nihm/Nehem, but also much more such as what lies to its east.

Nevertheless, Jenkins instructively shows how simple it can be to lose site of Nahom and the entire corpus of Arabian-related evidence. It is simple as showing that hey, Niebuhr published a 1796 map showing Nehhm on it (this is presented as an important discovery that threatens the Mormon position, when it has been a vital part of what Mormons like Warren Aston have presented from the beginning). And sure enough, Niebuhr’s work is listed right in Joseph’s vicinity, over at Alleghany College, PA or in the Medical Library at Philadelphia. Alleghany College is just 220 miles away from Palmyra, where the Book of Mormon project started, or just 50 miles from Harmony, PA, where Joseph went to escape persecution and do the actual translation before returning to Palmyra to publish it. Fifty miles would have been an much easier trip for Joseph Smith, who, as Jenkins seems to imagine, was an insatiable bookworm who naturally would have sought out every opportunity to do research to come up with a way to add a little “local color” to, um, one verse of the Book of Mormon.

After showing that Nehhm or related variants did make it on some early maps printed in Europe, Jenkins says this is “damning” evidence and forces us to the conclusion that Joseph got Nahom from a map:

The map evidence makes it virtually certain that Smith encountered and appropriated such a reference, and added the name as local color in the Book of Mormon.

Some European maps certainly circulated in the US, and the ones we know about are presumably the tip of a substantial iceberg. I have not tried to survey of all the derivative British, French and US maps of Arabia and the Middle East that would have been available in the north-eastern US at this time, to check whether they included a NHM name in these parts of Arabia. Following the US involvement against North African states in the early nineteenth century, together with Napoleon’s wars in the Middle East, I would assume that publishers and mapmakers would produce works to respond to public demand and curiosity.

So might Joseph Smith have looked at a map in a bookstore, been given one by a friend, seen one in a neighbor’s house, discussed one with a traveler, or even bought one? After all, there is one thing we know for certain about the man, which is that he had a lifelong fascination with the “Oriental,” with Hebrew, with Egypt, with hieroglyphics, with his “Reformed Egyptian.” He would have sought out books and maps by any means possible …. No, no, I’m sorry to suggest anything so far-fetched. It’s far more likely, is it not, that he was visited by an angel, and discovered gold plates filled with total bogus misinformation in everything they say about the Americas, but with one vaguely plausible site in Arabia. Ockham’s Razor would demand that.

And yes, I’m joking.

The mature Joseph, after translating the Book of Mormon and having numerous revelations and other experiences, does show a fascination with the antiquities, as we also should, IMO. But that’s not the young boy his mother knew, the unschooled farmboy whom she described as not being one who was bookish. He was not a bookworm and did not have some vast collection of books he consulted in preparing the Book of Mormon. He didn’t even have a manuscript with him as he verbally dictated the text to his scribes. If he sought out books and maps, where were they? How did he use them? There’s not a shred of evidence apart from wishful thinking that he went through any such process.

There’s no evidence that Joseph had access to any information that could have helped him craft First Nephi 16-17, and if you look at the maps of the day, you’ll struggle to see how any of it could have helped. Give it a try and explain to me, seriously, how those complex maps give one any guidance about where to turn and how to end up at the then-unknown outstanding candidate for Bountiful in modern Oman. And try finding NHM names every 5 kilometers or so! Or explain to me, if Joseph, in an effort to add a little local color or enhanced plausibility to his account, tracked down a detailed map and used it, perhaps after a lengthy and rather uncharacteristic journey to a large library, why would he fail to use more than just one word plucked seemingly from random off the map? Why would he use a name that none of his readers would have ever heard? Why not mention Mecca, Sana’a, Marib, or Aden? Why not actually use the map to make some major contributions to his work and reduce the risk of massive blunders? If he had all the maps of Arabia in his day before him, there’s no evidence that they helped a whit. Talk about lack of significance!

Perhaps the real question, Dr. Jenkins, might be this, if you’re interested in the issue of significance: What is the significance of the evidence that Joseph did research in remote libraries, or studied and used maps of Arabia from any source, all in the name of, apparently, selecting one word (or perhaps one word and if he were really clever, the south-southwest direction) that ends up not being a recognizable and widely known name right off the map that serves some “local color” function but is a name in the Bible that is spelled much differently than the obscure, unknown, apparently randomly selected place name he supposedly plagiarized from Niebuhr’s map? That’s a lot of work for apparently no gain. And if he did hope to capitalize on all that work by pointing to evidence from the Arabian Peninsula, why did neither he nor any of his co-conspirators (for the sake or argument) ever say a word about Nahom as some kind of evidence from Arabia? Why did no one ever even notice this until over a century later, when some Mormons began to take the Book of Mormon seriously and found, to their surprise, that there is evidence in Arabia for plausibility?

By the way, how long do you think it would have taken to “translate” a fraudulent Book of Mormon if Joseph had to track pore over books and maps to come up with a made-up concept every verse or two? In any case, I hope you’ll reconsider that argument.

There’s more to discuss in my next post on this topic, for a much more serious and carefully written critique of the Arabian Peninsula evidence has been offered elsewhere that may catch many Mormons off guard, for it is based on more careful arguments and draws upon some important modern scholarship on the Documentary Hypothesis. The answers aren’t so easy this time, not for me, anyway, but it’s definitely worth discussing and thinking about. And I’ll need your help in exploring the issues. Until next time.

"…NHM inscriptions occur every five miles in the Arabian peninsular…"

Be that as it may, I doubt Joseph Smith was aware of this. I would never tell anyone that 'because archaeologists found a city the matches the description of Nahom in The Book of Mormon, that means that The Book of Mormon is true.' Everyone seems to miss the main pitch that it is the Spirit that brings us evidence that The Book of Mormon is true and that Jesus Christ is the Messiah. It doesn't come by archaeological evidence. God wants us to trust in Him more. 1 John 4:2 says, "Hereby know ye the Spirit of God: Every spirit that confesseth that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is of God:" The Book of Mormon does just that. Problem=solved.

Great post, Jeff. If you're talking about tackling RT's series on NAHOM, you're right that it's well thought out and abundantly documented. However, I think one of its weaknesses is that he doesn't seem to allow enough room for the kinds of readings that the Book of Mormon may offer when it is approached as a *religious* text. Here's a little exchange we had on his blog:

RT: "If someone wrote a modern travel account from Ogden to St. George and the only city they happened to mention was Vernal, would that be relevant?"

Me: "Probably not. But what if the narrative isn't primarily a travel account? Or, at least, an account that has less to do with the physical journey and more to do with the spiritual or metaphorical journey? If so, then "Vernal" could become highly significant depending on the events that occur there or its placement in the metaphor or what-have-you."

Anyway, my two cents.

Jack

What is evidence in archaeology? It varies. If you discover a whole ruined city, then that is decisive evidence that some people once lived in it. Once you have that basic proof that some kind of human society existed there, you can use much more tenuous evidence to try to build a best guess at how those people lived. So a fair amount of published archaeological literature consists of stretching webs of conjecture between sparse points of ambiguous evidence. If you take that to represent the accepted standard of evidence in archaeology, however, you're missing something essential. You can only count the tenuous hints as evidence once you have the ruined cities.

That's what I think of, anyway, when I see a guy like Philip Jenkins insist that NHM is the only piece of archaeological evidence that has ever been presented for the whole Book of Mormon, and then see a guy like William Hamblin retort that there is a ton of other archaeological evidence (only he won't mention anything in particular). My guess is, they're both right — but really only Jenkins is right, because the ton of stuff that Hamblin considers evidence is tenuous hypotheses that would be respected archaeological theorizing if — but only if — we also had decisive evidence that the hypothesized ancient societies were really there. In effect Hamblin is standing on cargo cult archaeology, whose careful practitioners go through the motions of archaeological reasoning the way that post-WW2 Pacific islanders built bamboo radar dishes to try to lure back the cargo planes. They reproduce the activity but lack the essential basis that makes it work.

Three letters on a rock is no Troy; but okay, it's something. Coincidence of location with a Book of Mormon description would be something further. But just how unambiguous is that Book of Mormon description? If you didn't know where this NHM inscription had been found, would you really be so sure that this point was exactly where Nephi was describing? To pinpoint a real location in Arabia might have been tough for an uneducated farmboy, but it wouldn't have been nearly so hard to write a few vague lines about rivers and oases, and then let 21st century Mormon apologists paint the bullseyes around the bullet holes.

I'm not an archaeologist. But those would be my concerns.

This comment has been removed by the author.

One detail: getting Nahom from Nihm. Why would Hebrew travelers pronounce NHM as Nahom, if what they heard was really Nihm? Are you suggesting that they didn't actually hear the place called Nahom, but read NHM on the roadsigns?

DSRT DRY

DSRT HT

HRD T FND

PCNC SPT

BRM SHV

Great post as always, James. I'm interested in reading Jeff's response.

Something that always catches my eye involves the translation process evidence that Jeff often leans on: "He didn't even have a manuscript with him as he verbally dictated the text to his scribes…"

This statement has already been proven false by the clear evidence of KJV errors and added italicized words are found in the BoM and severely damages the credibility of eyewitness accounts of how the BoM was written. They all testify Smith did not have a bible during the translation process, the evidence contradicts this.

Again, Jeff admits how troublesome this issue is and knows the only reasonable explanation is that Joseph Smith did in fact have a Bible with him while writing the BoM.

This all leads to the very likely case that Smith and the "eyewitness" did not tell the whole truth to how this book was written and opens the doors to all kinds of other theories.

Sorry, I hit the wrong selection, anon 6:52 is flying fig.

My point is by establishing the fact that Smith used a Bible while writing the BoM (which the evidence clearly shows) proves that with the eyewitness lied or were lied to by Smith. This now calls into question the entire account of where the BoM came from, how long it took to write, what other sources were used, who else was involved.

Yet again Mormanity is quite anxious to trash Chris Johnson with his little plagiarism straw man. As I discussed in his initial response at Mormanity, Johnson was actually defeating a critic’s argument (Anthon 1827) that were even stronger than the NHM bit, much like Mormanity does with Curmoah-Moroni or I do with Lincoln-Kennedy. Johnson did not argue that JS borrowed the word Nahom from existing material. Mormanity’s frustration has compelled his intellect to repeat the deception.

The consistency of the human condition is indeed fascinating. Iconoclasts such as Mormanity are consistent to group conformity, right or wrong. An iconoclast such as John Dehlin had the courage at a young age to say what was happing (in his mission) was wrong and constant with his person did the same thing as an older adult.

The LDS leadership defended the younger Dehlin and inconsistently not the older. Real humans are consistent. Groups of people that we tend to personify of course rarely are (LDS, Mormons, LDS Leadership, etc).

Hey Jeff, I enjoy your blog a lot. I just wanted to say that I've just written a post that is related to 1st Nephi's relationship to the Exodus, which you might find relevant to your next post. I don't think anyone else has written about this before, so it's exciting for me, and though it doesn't vindicate Nephi's use of the exilic or post-exilic compiled pentateuch, it does show the likely use of another source that in all likelihood was far beyond Joesph's reach, the Talmud! Check it out: https://seersandstones.wordpress.com/2015/10/13/book-of-mormon-relationships-part-ii-caleb-nephi-and-the-talmud/

I haven't read RT's second post yet, but when I finished reading the first I thought of the same general question as James — What counts as evidence? — and was struck by the importance of the presuppositions we bring to the table. If we presuppose the historicity of the Book of Mormon, then NHM is evidence of that historicity; otherwise, it's just a coincidence.

Let me get at my point by making an extended analogy with coin-flipping (and please accept my apologies in advance for the length). The analogy is not really about the historicity of the BoM; it's about the debate over the historicity of the BoM.

There is a controversy about a certain coin. John thinks this coin has been rigged to significantly favor heads. Jane thinks the coin is just a regular coin.

John and Jane flip the coin five times, and the result is heads 3, tails 2.

"Aha!" says John. "That's exactly what my theory predicts."

"Not so fast," says Jane. "Five is an odd number, so it was inevitable that we would get at least one extra head or tails, and the fact that the excess happened to be heads is just a coincidence."

At this point, both John and Jane might well be right. The results thus far are consistent with either hypothesis. Note that we can legitimately use the term evidence to refer to these results, but John will consider the results to be evidence for his view and Jane will consider them evidence for hers.

Anyway, if we want to know who's right, we need more evidence. So we flip the coin five more times, and once again we get 3-2 heads, for a total of 6-4 heads.

This result is predicted by John's hypothesis. But it is also predicted by Jane's: if the coin is indeed legit, the most likely result of ten flips is 5-5, but the odds of getting 6-4 are still pretty good.

What we really need to do is a lot of flips — say, a hundred. Jane's theory predicts that the results will converge on 50%, and John's theory predicts they will converge on some higher percentage. So together our two opponents perform 90 more flips, with this result:

51-49 heads.

"I win!" says John.

"Nuh-uh," counters Jane. These results support my hypothesis more than yours. My hypothesis predicts a convergence on 50-50, and that's exactly what we've seen. And remember, your original hypothesis included the word 'significant,' and the slight difference we see in our results are not statistically significant."

"Not so," says John. "'Significant' is not the same as 'large.' When I used that term I meant something like 'measurable.'"

Says Jane, "You're just moving the goalposts…."

Obviously, hypotheses about BoM origins are much more complex than those about coin-flipping. One of the points I'm trying to make is about the word evidence and how we use (and misuse) it as we conduct these seemingly interminable debates. Bear with me as I expand on my analogy in my next comment. (The whole thing is too long for Blogger, so I've split it up.)

Next, imagine that, instead of John and Jane conducting the hundred coin flips themselves, in real time, those flips were conducted, and the results honestly recorded, by someone other than John or Jane, without John or Jane being present. That is, the results of the flips are now a matter of historical record. They are facts, but John and Jane do not as yet know what all those facts are. They have only their competing hypotheses, which they are now, in my thought experiment, going to try to prove the only way they can — because, gosh darn it, the coin itself has been irretrievably lost and is no longer available to be flipped — by gradually uncovering the pre-existing record of the hundred coin flips.

As John and Jane go about their digging, they first uncover the record of the initial five flips (3-2 heads) as described above, and after uncovering that evidence they have the same conversation as above. Next they uncover the record of the second run of five flips (rsulting in 6-4 heads).

We are now at the point where I said: This result is predicted by John's hypothesis. But it also predicted by Jane's: if the coin is indeed legit, the most likely result of ten flips is 5-5, but the odds of getting 6-4 are still pretty good. The difference is that instead of having John and Jane themselves perform 90 more flips, they are going to undergo a piecemeal process of gradually uncovering the rest of a preexisting evidential record, a little bit of it here, a little bit of it there. (The idea is to improve the analogy by making the simplicity and clarity of coin-flipping a bit more like the complexity of archaeology.)

What kinds of things might happen as John and Jane uncover parts of the record? They might discover a fragment that looks like this:

Flip #67: HEADS

Flip #68: TAILS

Flip #69: TAILS

"Aha!" says Jane, as John grumbles something about how, by itself, this discovery doesn't really mean very much.

A year later someone discovers another fragment of the record, and it looks like this:

Flip #31: TAILS

Flip #32: HEADS

Flip #33: HEADS

Flip #34: TAILS

Flip #35: TAILS

Flip #36: HEADS

These fragments certainly constitute evidence — but evidence of what exactly? The known evidentiary record is still consistent with either hypothesis. This would be true even if we next discovered a fragment reading like this:

Flip #48: HEADS

Flip #49: HEADS

Flip #50: HEADS

Flip #51: TAILS

Flip #52: HEADS

Flip #53: HEADS

Flip #54: HEADS

"Bingo!" crows John. "What are the odds of flipping an ordinary coin seven times and getting 6-1 heads? Clearly this is no ordinary coin!"

"Not so fast," says Jane (no doubt with a weary sigh). "The odds of flipping an ordinary coin seven times and getting 6-1 heads are slim indeed, but that is not what has happened here. What has happened is that someone has flipped a coin a hundred times, and in the course of doing so produced a couple of runs of three. The odds of that happening are not slim at all. In fact one would expect it to happen occasionally."

Says an equally exasperated John: "You're just refusing to look honestly at the evidence that we actually have…."

I could go on, but I hope this analogy as I've developed it thus far will shed some light on the frustrations we're all experiencing in these debates. None of the BoM evidence is a smoking gun; all of it boils down to questions of probability and interpretation, which two things in turn hinge a great deal on the presuppositions we bring to the table and the way we frame our hypotheses.

I guess I will go on, just a wee bit more. What we have at this point in my analogy is that John still believes the coin was a little bit rigged. And why wouldn't he? That's what he thought going in, and the evidential record hasn't conclusively disproved it.

Jane also still believes what she believed from the start. To Jane, the idea of a coin being rigged seems inherently less likely than not, and she certainly hasn't seen anything remotely like the kind of evidence that would be needed to win her over.

In the absence of a smoking gun, believers gonna believe and doubters gonna doubt.

And lest anyone think I've gone soft, let me just add one more thing: No one who is not already committed to the idea should be persuaded of the historicity of the Book of Mormon by the evidence we have. The evidence we have is simply not sufficient for that.

Of course, if one allows oneself to be persuaded by something other than actual evidence — by what Jeff would call the spirit or whatever — well, that's a different story.

I want to add one last thing… for now, at least.

Based off of my study of the Hebrew language (historically speaking & not so much linguistically), I would recommend that people not jump the gun in assuming the pronunciation of the word 'NHM.' At the time of Lehi and his family, Israel was speaking a very different Hebrew than what is spoken today. The Hebrew I'm talking about (and I can't remember completely if it is Paleo-Hebrew or a not-so-distant variant) was spoken between 1200 & 586 B.C. (rather convenient, if you consider the Babylonian exile during the time of Lehi and his family which also transitions into my next point). At the point of the Exile, the Jews were practically forced into speaking the language of the Babylonians (a variant of Aramaic). Hebrew was only kept alive for a short time and eventually the alphabet changed drastically, borrowing from the Aramaic instead of the Phoenician alphabet.

To add onto that, the Hebrew language eventually died as a spoken language. While the pronunciation of words had been preserved (barely), the meaning of a lot of different phrases and words were difficult to maintain. Eventually, it's revival began in the 1880's. So, we have a different alphabet and different grammar style and different words. Do we really even have the same language? NO!

Basically, what I am trying to say is that, as far as research tells us, there is no official way to know how to pronounce how the 'NHM' should be pronounced. However, it should be known that these are the transliterations of words that do have the 'NHM' construction: Nahum, Naham, Nihm, Nehem and Nahm. It should be noted that there is a possibility of a different pronunciation of the word and that it is completely dead to mankind with the exception of its preservation in The Book of Mormon.

"No one who is not already committed to the idea should be persuaded of the historicity of the Book of Mormon by the evidence we have. The evidence we have is simply not sufficient for that."

But, if, for the sake of argument, the Book of Mormon were found by trained archaeologists and translated by trained linguists then the current "evidence" would be evidence indeed.

Re: Coin flipping — You're analogy assumes that John will, in the end, never produce evidence beyond anything coincidental (Pardon the pun). Therefore, it is inherently biased.

Jack

Jack, where in my coin-flipping analogy do I make that assumption?

To be perfectly honest, even if the Book of Mormon were found on gold plates that were still preserved, and translated by experts, most people would suspect that it was an elaborate hoax, because its content seems so unlikely for a real ancient record. In such a case, though, I guess (I'm not an archaeologist) that NHM might count about as much as it does now — a little detail that is worth something, but that might line up either way.

OrbitingKolob's analogy is indeed biased: from the fact that he has 100 flips coming out very close to even, we can deduce that his John is almost certainly wrong. But this is his point: the quality of ancient Book of Mormon evidence looks a lot like the kind of random coincidences that could happen even if the Book of Mormon were fiction.

From a Mormon apologist's point of view, that conclusion may be frustrating. I can see how it might feel as though skeptics are simply so biased that they will not recognize any evidence whatever, no matter how much effort apologists make to uncover evidence. But from an outsider's point of view, I'm afraid, it is the Mormon apologists who are being unfair, because they are refusing to accept that the standard of evidence that is demanded — and that is met — in real archaeology is enormously higher than even their best efforts have managed.

Playing with coincidental parallels and plausible matches is to archaeology what the putting game is to golf. It's a real and important part of the discipline, and real professionals work hard at it. But the putting game doesn't even start until you get on the green, with something like a ruined city to prove beyond all doubt that there was something there. Ancient Book of Mormon studies seems to me to be playing mini-golf, where it's all putting. Mini-golf does take some skill and effort; but it just isn't enough to get you into the PGA.

NHM is at best a putt. In mini-golf it would be a nice play, but It's not a tee shot. There hasn't been a tee shot yet, in ancient Book of Mormon studies. This is what guys like Jenkins are saying, I think.

Ah, now I see the reason for saying my analogy is biased. It's a fair point, and I acknowledge that yes, Jack, my understanding of reality is baked into my analogical cake. So, let's go ahead and take that assumption out. Let's say that we don't know whether the final results of all 100 flips converge on 50-50, and that we only know as much of the record as I described above. The basic point, I think, remains the same: the evidence could support either hypothesis, so that the decisive factor becomes not the evidence but the presuppositions we bring to our interpretation of the evidence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cahokia

Cahokia is a buried city in the state of Illinois and dates back to ~600 B.C. Read more about it at the above link.

There's two ways to look at it. Either The Book of Mormon is right or The Book of Mormon is wrong. The thing to keep in mind is that The Book of Mormon isn't a historical record. It's a spiritual record. We may never find exact archaeological evidence for it, but what has been found makes The Book of Mormon all too real to be just a made up book that Joseph Smith decided to write one day.

To my mind, Cody, there are more than just two ways to look at it. What the evidence tells me is that the Book of Mormon is neither "right" nor "wrong," because it's essentially a myth–an American religious myth–and myth is not the sort of thing to which words like "right" and "wrong" can sensibly be applied.

Is the Greek myth of Sisyphus right or wrong? What a silly question!

Of course, the things we say about the myth of Sisyphus (or the Book of Mormon) can be right or wrong–e.g., it's wrong to say it's history, or that its value lies in its historical accuracy, and so on, just as it's wrong to say such things of the Book of Mormon.

Orbiting Kolob, you are right. Thank you for the correction. What I should have said is that it is either True or False. Even then, it still depends on what context I am speaking in. One could say, "The Book of Mormon is true." and only mean that it is a spiritually true record, but they don't think that it something that really happened and took place. On the other hand, one could say, "The Book of Mormon is false." and be referring to it as something that actually took place in history, but they could think/believe that it is a good, spiritual book. We could delve further, but I think that would just be splitting hairs.

Cody,

It isn't even a matter of "true" or "false."

Here is the way to word the question:"Is the Book of Mormon an authentic ancient record of a group of people who lived in the Western Hemisphere during the time period in which the book claims they lived?"

As for the "spiritual truth" of the book, well…if the answer to the question above is "No," then it doesn't matter if the book contains "spiritual truth," because the book is a fraud and the man and organization that continues to spread it across the globe are both frauds.

I could write a book that contains a pure Gospel/Christian message. My book could basically include the entire Gospel as understood by Mormons. But if I claim I found the book during an alien abduction and brought it back with me, and then I used this book to lure people into my church, I would be a fraud, and despite all the Christian truth in the book, it would be a deceptive tool. A fraud.

So, the authenticity of the book is essential to the claims of the church. It HAS to be exactly what it claims to be, or else the entire thing is a fraud.

flying fig: The evidence doesn't clearly show JS used a Bible. Sorry. If you want to say he used a Bible, then you must admit he used at least 3 different Bibles. Also, most KJV "errors" are not errors, just declared errors. Also, the italics assertion is bogus.

everythingbeforeus,

"Is the Book of Mormon an authentic ancient record of a group of people who lived in the Western Hemisphere during the time period in which the book claims they lived?" & "It HAS to be exactly what it claims to be, or else the entire thing is a fraud."

In other words it's a matter of "true" or "false." Did it happen or didn't it happen? Is The Book of Mormon true or is it false? It's as simple as that. Thank you for reiterating what I just said.

No, Cody,…

The parable of the prodigal son, I assume you would agree, is "true." But it isn't literally true. It is a parable that teaches truth. If Jesus taught the parable as something that really happened, while it might contain truth, it would also be false. And the teacher would be a liar.

The Book of Mormon can be true, but only under two conditions: 1)it is a work of fiction that teaches truth and it was presented as such; 2) it is exactly what it claims to be, and the ideas it teaches are indeed true.

So, I think we agree in some ways, but in other ways, I think it is more nuanced.

"The Book of Mormon can be true, but only under two conditions: 1)it is a work of fiction that teaches truth and it was presented as such; 2) it is exactly what it claims to be, and the ideas it teaches are indeed true."

So, in other words, The Book of Mormon is either true or false. Why shear a pig?

1 John 4:2 says, "Hereby know ye the Spirit of God: Every spirit that confesseth that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is of God:" The Book of Mormon does just that. Problem=solved.

Cody,

Okay I'll grant that perhaps I am shearing a pig. But why did you have to go and bring 1 John into it?

First of all, the Book of Mormon is not a "spirit." It's a book. John doesn't say that "every book that confesseth that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is of God."

John is talking about how we can discern spirits, not books. The Jehovah's Witnesses will preach that Jesus Christ came in the flesh. But it does not therefore follow that the Jehovah's Witnesses are correct in everything else that they say. Do you believe that the Jehovah's Witnesses are "of God?"

Do you believe that the Catholics, Anglicans, Calvinists, and Lutherans are all "of God?" Is the problem really solved that easily for you?

"Do you believe that the Jehovah's Witnesses are "of God?"

Do you believe that the Catholics, Anglicans, Calvinists, and Lutherans are all "of God?" Is the problem really solved that easily for you?"

I don't know. It sounds like you're the only one who has a problem with it. I'm trusting the Holy Ghost on this one, not you.

Cody,

This answer seems like an evasive tactic. You say you don't trust me, but I haven't really said anything yet that I have asked you to trust. I have really only asked questions. Do you think Catholics are "of God" because they confess that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh? That answer is either "Yes," "No," or "Kind of…"

"Do you think Catholics are "of God" because they confess that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh?"

Well, they certainly aren't of the Devil. I don't think it's the Church that matters as much as it is the doctrine. Do the Catholics really believe that Christ came in the flesh? Look at the rest of their doctrine. By their fruits you shall know them.

"I have really only asked questions"

That's a lie in itself. You've done more than asked questions. Not that it's bad that you've done more. It's just not honest of you to say. You should probably be a bit more thorough.

Cody,

I don't mean to lie. We had a brief discussion about shearing pigs, and I granted you that I was shearing pigs. A point for you.

Then, I provided some backdrop for a few questions. I can't remember making any truly declarative statements. Oh well… If I did, I take it all back then. Another point for you.

Okay…this is starting to get good now. So, if I am understanding you correctly, you are telling me that Catholics may preach that Jesus is come in the flesh, but their "fruits" suggest otherwise. This is rich! We'll just let that stand. If you agree that I have adequately summarized your point, I'll put you on the record. The Catholics, all 1.2 billion of them (that is 1,185,000,000 more people than are on the LDS church's records), do not produce fruits worthy of a believer in Christ. All those Catholic hospitals, orphanages, schools, and humanitarian organizations just don't cut it?

"The Catholics, all 1.2 billion of them (that is 1,185,000,000 more people than are on the LDS church's records), do not produce fruits worthy of a believer in Christ. All those Catholic hospitals, orphanages, schools, and humanitarian organizations just don't cut it?"

I mean if you want to blanket all of the Catholics in that sense, then how about we talk about the molestation of children? 1/3 of Catholic clergy molested children. 1/3 knew and didn't say anything. And 1/3 didn't care once it was revealed.

If you were to ask me, I would say it depends on the individual person because God looks on a persons heart, but if we're gonna do it your way, then lets condemn the whole Catholic Church for child molestation and not leave any wiggle room for repentance.

It should also be noted that just because someone is a Latter-day Saint that they aren't necessarily saved. Following Jesus Christ is a continuous process, not a milestone that you can sit at for the rest of eternity.

Cody,…

You are the one who said the Catholics don't produce Christian fruit, more or less…not me!

You are confusing me now. But moving on…

Quoting you: "It should also be noted that just because someone is a Latter-day Saint that they aren't necessarily saved. Following Jesus Christ is a continuous process, not a milestone that you can sit at for the rest of eternity."

I know Jeff is going to get on my case for diverting this conversation away from NHM, but you are really tempting me when you start saying stuff like this. You are indeed correct that not all Latter-day Saints are saved. Dallin H. Oaks said that if we define "saved" to mean "exalted" there is no Latter-day Saint in all the world that can confidentally declare that they are "saved" while in this mortal life.

Not a single one.

So, I will ask you this question: At what point in your life, Cody, do you have the assurance that you have eternal life?

"You are the one who said the Catholics don't produce Christian fruit, more or less…not me!"

You were the one who implied that the partial production of Christian fruit means that the whole entity is good. I was merely pointing out that it doesn't go as far as we think it does. Some people do good things. Some people do bad things. However, you can't do bad things and expect to be praised as having done good. Jesus said something to this degree about people who would wrap up a dead body and make it look and smell all nice. In other words, you can dress a monkey in silk, but… you still have a monkey.

"So, I will ask you this question: At what point in your life, Cody, do you have the assurance that you have eternal life?"

Well, the answer to that question is given in your last as you quoted from Dallin H. Oaks "Dallin H. Oaks said that if we define "saved" to mean "exalted" there is no Latter-day Saint in all the world that can confidentally declare that they are "saved" while in this mortal life."

Which isn't the exact quote, but to add to what you've said, Dallin H. Oaks also stated (in this same talk if I'm not mistaken), "That glorious status can only follow the final judgment of Him who is the Great Judge of the living and the dead. I have suggested that the short answer to the question of whether a faithful member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has been saved or born again must be a fervent “yes.” Our covenant relationship with our Savior puts us in that “saved” or “born again” condition meant by those who ask this question."

However, I can't play God and declare myself into His kingdom. I will let Jesus Christ petition my entry. That is how salvation works.

Cody.

What do you have against monkeys that even silk won't help?

I think we are not connecting in what we are saying when it comes to the Catholics. And I think the misunderstanding is so deep now that I would make it worse to try to clarify it. Anyway…

But about salvation/exaltation…I agree that we don't declare ourselves into God's kingdom, but isn't that kind of what you are doing when you tell your bishop you are worthy in every way to enter the House of the Lord? Isn't the temple the symbolic representation of the Celestial Kingdom? Aren't you therefore in effect declaring yourself worthy of Celestial glory?

Also, let me tell you the good news. There is no "short answer" and "long answer" to the question of whether you have been saved or born again. There is just one answer. Period.

The church has a "short answer" to that question so that it can continue to look like a Christian denomination. It has a "long" answer also so that it can demand from you that which the organization requires to survive, namely your money, time, and your unwavering loyalty.

1 John (this is why I asked you why you had to go get John involved) tells us that if we have the Son then we HAVE eternal life. Notice the present tense? Not future tense. If you have the Son, you have eternal life. Don't let them tell you otherwise. What do you think it means when Jesus said his burden is light?

Hi everythingbeforeus,

but isn't that kind of what you are doing when you tell your bishop you are worthy in every way to enter the House of the Lord?

– No

Isn't the temple the symbolic representation of the Celestial Kingdom?

– Yes

Aren't you therefore in effect declaring yourself worthy of Celestial glory?

– No

I believe that you are referencing 1 John 5. Here are the first handful of scriptures:

5 Everyone who believes that Jesus is the Christ is born of God, and everyone who loves the father loves his child as well. 2 This is how we know that we love the children of God: by loving God and carrying out his commands. 3 In fact, this is love for God: to keep his commands. And his commands are not burdensome, 4 for everyone born of God overcomes the world. This is the victory that has overcome the world, even our faith. 5 Who is it that overcomes the world? Only the one who believes that Jesus is the Son of God.

Steve

PS – I believe it was you who said that the missionary discussions from the early 90's never brought up Jesus as the Savior. I found my discussions.

Lesson 1, second principle – Jesus Christ, Son of God (first principle talked about God). Complete with scripture references. 3rd principle, Jesus Christ, His witnesses and the plan of salvation. Principle 4, Joseph Smith as a modern witness of Jesus Christ, etc (more references to Jesus Christ in succeeding lessons).

If I didn't know better, I would say that you seem to be trying to misrepresent the Church.

Steve,

You are mistaken. I said the missionary discussions never required the missionary to commit the investigator to pray to receive a spiritual witness that Jesus Christ is the Savior. They were only to pray about the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith. I am not trying to misrepresent the church. Is it not a conceivable possibility that those who are critical can also have honest grievances. I am confident that if you look back over your missionary discussions you will see that each discussion had certain commitments associated with them. Lesson one commitment invitation is read BoM and pray to see if it is true. Lesson two is invite to be baptized. Three is attend church. Four is word of wisdom and chastity. Five is tithing. Six is accept a calling.

As for 1 John, sure, John says to keep the commandments. But those commandments do not include so many of the commandments that Mormons claim are the commandments of Jesus Christ. If you read the entire 1st Epistle of John, it should be more than obvious that the Commandment of Christ is to love one another. John frequently emphasizes "that which we heard from the beginning." In 3:11 he says that this message we had from the beginning is love one another. In 3:23, he says again that "this is the commandment, that we should believe on the name of..Jesus Christ and love one another." John also says that all the law is fulfilled in this: love one another.

John says nothing about the requirements of Mormon Law. The Word of Wisdom (Paul and Christ actually preach against required dietary restrictions). Temple ordinances. The wearing of garments. The paying of tithes (membership dues) to the church. Etc…

All the law is fulfilled in this: love one another.

You cannot read the simple words written in the Epistle of John and find justification for all that you do as a Mormon to work your way toward exaltation.

You are either deluding yourself, or you have been deceived by others, if you think you can.

Again, everythingbeforeus misrepresents the Gospel, and John in particular. There are plenty of sermons in the LDS church on loving one another. But that's not the gospel of Christ, is it?

It comes back to the fundamental mistake you evangelicals make: you assume that isolated statements from epistles overrules the Lord's commandments. The Lord preached the Sermon on the Mount. That says nothing about "love is all you need," which is what you are trying to turn the gospel of Christ into. Next you'll be saying the Beatles were prophets of God, right? They preached the same thing.

Jesus frequently made people sacrifice enormous things for Him. To the rich man he said to sell all he had and follow Christ. That's not "Love is all you need!" He preached the exact opposite of your doctrine; saying that not everyone who calls Him Lord will enter into heaven, but only those who did His will–i.e. followed the commandments.

Your view of the gospel is simplistic: that Jesus is the Forgiveness Fairy, and sin no longer matters. You are preaching the gospel of Nehor, in a slightly modified form. Mixed with the Zoramites, really. God doesn't care what you do as long as you say you believe in Him. Right? Jesus suffered for you so you don't have to do anything–He has it all covered. So do what you want, man!

You have a very fundamental misreading of God Himself, as well. Which I will discuss in my next post.

The fundamental question evangelicals never face: Is God the same, yesterday, today and forever? I assume you would say yes. Then why the law of Moses? And what did the Law of Moses actually attempt to do? And why is that important to us today? And why, if the Gospel is so easy that all you have to do is say "Jesus saves!" and that's it (which is what the whole point of "you aren't saved by works, only by grace" is all about–to eliminate the need to keep the Commandments of God) –why was the Lord so cruel in telling the Jews to live the Law of Moses, and then let everyone off the hook 1500 years later? He then is respecter of persons? The Jews needed the whip of the Law, but the rest of us get smooth sailings?

Nonsense. The Law of Moses was not repealed in the sense that commandments and ordinances went away. Indeed, the ordinances we LDS follow today have direct analogues to the Church that Moses set up. The Lord instituted the Sacrament to replace the Passover feast; but the point was the same: to be "passed over" from the destroyer. The Temple had shewbread, washings and anointings, and so forth. Do you really think that God just decided the whole idea of Ordinances and covenants was passé when Jesus was done? Then why put them into action in the first place? Surely God knew the whole plan.

The point, as Paul said, of the Law of Moses was to be a schoolmaster to bring people to Christ. How, therefore, did that work? What was the point of sacrificing the lamb, the pigeons, the Sabbath day, the Temple, etc. if the ultimate end of all of that was "Go home and relax on the couch; as long as you love your neighbor it's all good!" What was the point of all that focus on covenants made, and punishments for covenants broken if Jesus was just going to eliminate covenants?

Or was it to teach people how to make and keep covenants with God in general, and Jesus introduced higher, better covenants? He did with the commandments; such as adultery being redefined to be lusting in your heart as well as cheating on your spouse. Higher levels of covenant keeping; higher rewards available.

This is stuff evangelicals shy away from; but then you cannot explain why God would punish the Jews with all that Law of Moses stuff when the Gospel is so easy. The evangelical version of Jesus bears no resemblance to the God of the Old Testament. Are they not the same Being? If so, why would He change His emphasis and totally change worship from demanding to even Nancy Pelosi can be considered saved?

This is why many Christians don't consider Mormons Christian. Regardless of who (if anyone) is actually right about God, Mormons like Anon 1:40 differ as much in salvation theory from the great majority of self-identified Christians as they differ in belief about the nature of God. Indeed, non-Mormon Christians and Mormons probably differ as much from each other on these essential points as they both differ from Orthodox Jews or Muslims.

I don't think I have anything to contribute to this argument other than that. I call myself a Christian and I believe that God doesn't change, but I believe that human understanding of God has changed a lot, and that ancient scriptures represent ancient human understanding, not God's complete truth for all time. So I don't see why Moses's soteriology is any more permanent than Moses's astronomy. I believe in continuing revelation.

Anon 1:40 writes, The point, as Paul said, of the Law of Moses was to be a schoolmaster to bring people to Christ.

I find this statement (and the widespread Christian belief underlying it) to be fascinating. My first response was something like, "Gee, I bet certain Orthodox Jews would be just thrilled to learn that their religion was not a complete thing in itself, not an end but a means, a mere stepping-stone to Christianity."

Now that we have Christianity, the (Christian) thinking goes, Judaism is no longer necessary. There are certain implications of that which I think many Jews would not exactly appreciate.

But then it occurred to me that there are atheists who make very much the same kind of claim about Christianity. These would be atheists who acknowledge certain contributions that Christianity has made to the development of civilization generally, and to the rise of liberal democracy in particular — Catholicism gave us important institutions such as the university, Protestantism gave us the ideal of universal literacy, and so on — but now that we have those things, we no longer need the religions that gave them to us.

So here the thinking is very much the same as above: Now that we have our modern, secular liberal democracy, Christianity is no longer necessary. Protestantism was just a schoolmaster to bring people to secular liberalism.

Of course, the Christian will immediately object that Christianity is much more than just a stepping-stone to something else; the Christian will say, "My religion remains a vital force in my own life and that of millions of other believers, etc., etc., and to reduce it to a once-useful but now outdated stage of history is both mistaken and demeaning."

But the Jewish believer would say the same thing about the Christian reduction of Judaism.

What goes around comes around.

Anonymous 1:27

Nothing overrules the commandments. Evangelicals do not believe this. Stop misrepresenting what they believe. That is a straw man Mormons love to throw into the mix. But that is just being lazy.

Nothing overrules the commandments, but the reality is that you can't live the commandments. So, what are you going to do? It is all or nothing. You can't just pick the commandments that come easily to you. You have to live all of them. So, what are you going to do?

Does the blood of Christ purchase the believer? Or does the blood of Christ purchase a ladder? Mormons believe that blood purchases a ladder, and then all they need to do is climb it. Jesus will help you along the way.

But exactly what does Jesus's help look like? What is the practical difference between using the Atonement to help you overcome smoking, for instance, and my agnostic father-in-law who denies the divinity of Christ but stops smoking in a few short weeks from sheer determination?

Can you explain this to me? Explain to me how grace really works as a Mormon. At what point do you finally earn that gift that, by definition, cannot be earned?

Jesus either buys YOU or he buys you a ladder. Mormons have a ladder. Good luck climbing it.

James Anglin: You are correct that Mormons differ from most Christians in a lot of areas. This, of course, is not surprising, nor is it a new insight. We don't claim to be "regular" Christians, in that we reject creedal Christianity. Someone once described Mormons as the Christianity that would have happened if Peter rather than Paul had "won out."

I think, Orbiting Kolob, you are deliberately twisting the relationship Jews have with Christianity. Most still accord Jews a vital part in our religion–after all, Christ was a Jew and the Old Testament is a part of our faith. I would suggest, however, that even if the Law of Moses is more "primitive" as you allege than Christianity, it is certainly worlds better than your view of secular liberalism. After all, the practice, everyday difference between Secular liberalism and the worship of Baal and Molech seems to be very small. Both worship the pleasures of the flesh and the gospel of "do what you want, there is no consequences." Your beliefs are really very little different than that of the Phoenicians; just with a few names changed.

Everythingbeforeus: it's not me that is misrepresenting Evangelicals. The frequent charge you guys make against Mormons is we believe in works and commandments; when that "denies the gospel of grace" or such. Well, if believing in works and commandments is wrong, then what is a commandment–what's the punishment for violating one? I would suggest that breaking a commandment means that, without help, you will never return to God. I think both sides agree on that. We both believe that Christ is the way to return; as He paid the price for our sins.

The difference, as far as I can tell, is this: you guys believe in salvation as an event; we believe it is a process. Once saved, always saved is a large dispute amongst Evangelicals, I know. The core concept for grace and Mormons is 1) "retaining a remission of our sins." and 2) progressing forward. It is not all or nothing, as you describe it. You evangelicals say "It's impossible to keep all the commandments. So why try?" I know this because you accuse Mormons of thinking we can earn our way to heaven by keeping the commandments. If the commandments are important, then why do you say we are wrong for trying to live them? If they are not important, then they aren't commandments, are they, and Christianity has no concept of sin. This is your theological muddle, not mine.

Continued….

Again, this goes back to core concepts: why does God care about us at all? What's the point, really? As best as I can tell, evangelical's believe that the end goal is, well, sitting on a cloud playing harps in-between walks with Jesus for eternity. I don't think there is any real idea of what we are supposed to do or be.

For us, we believe Jesus when He said he would make us joint heirs alongside Him with God, and that we would sit with Him in God's throne. If we are going to do that; then we have to live like that. And that's the purpose of commandments, of striving to be perfected: so we can, in fact, be perfected. We have a job to do, and it's not sitting there learning the C scale for our harps. The Commandments are for our benefit. The entire point of the Law of Moses was to teach the Jews to make and keep sacred covenants, to be God's people. To make something of them. Jesus didn't come to say, "no big deal, just keep doing what you are doing." His Law is to progress beyond the "Thou shalt nots" of the Law of Moses to the "Thou shalts" of His gospel. Nowhere did He revoke the "thou shalt not" of the Old Testament, aside from technical details here and there.