First, a word of apology. To prepare for this post, I reread an outstanding

book on the Documentary Hypothesis, Richard Elliott Friedman’s

best-seller, Who Wrote the Bible? , second edition (New York:

HarperCollins, 1997). I read the first edition (1987) in the early

1990s and was impressed, but wasn’t ready to really learn and

understand how significant his research was. Upon rereading, I found it remarkably interesting, even brilliant,

with a style that is reads a little more like a thrilling murder mystery

than a scholar’s review of esoteric research. But my second reading

requires this apology: My apologies to tennis stars Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic, and others for not paying full attention during their recent matches

at the Shanghai Rolex Masters Tennis semifinals on Oct. 17, 2015, where

I spent much of a Saturday trying to serve two masters–or rather,

trying to read while two masters served.

Overview and Summary

In

my previous post, “Burying Nahom,” I addressed a rather sloppy recent attack among the

Patheos.com blogs on the Arabian Peninsula evidence for the plausibility

of Nephi’s account in the Book of Mormon. Now I’d like to discuss a

much more careful criticism from another Patheos Blog, written by

someone much more familiar with the Book of Mormon who has the skills

and intellect to develop more powerful arguments against First Nephi.

I’m referring to the anonymous writer “RT” at Faith Promoting Rumor,

whose post “Nahom and Lehi’s Journey through Arabia: A Historical Perspective, Part 1” sets a high standard for Book of Mormon criticism.

RT

offers a variety of criticisms against the significance of Nahom and

related finds. While I feel he overlooks many vital points, I think he

makes a particularly interesting and serious criticism when he appeals

to the extensive biblical scholarship behind what is known as the

“Documentary Hypothesis” to suggest that First Nephi is obviously

fiction, and therefore the Nahom evidence doesn’t count because it can’t

possibly be anything other than coincidence. I’ll address other aspects

of his critique later, but I feel this is the part of his attack on

Nahom that most strongly demands a response. His tone is reasoned and

cautious, his approach seems reasonable, his documentation is thorough,

and his logic seems solid. In spite of that, RT, like Philip Jenkins,

the previously discussed “Nahom Follies” writer, misses some important

information.

As I’ll show below, one of the most important things he misses is the significant scholarship of Richard Elliot Friedman

who persuasively demonstrates that the priestly text, P, which provides

much of Pentateuch, was not a late manuscript from after the Exile, but

much more likely comes from the time of King Hezekiah, dating it to

before Nephi’s time (see Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible, second

edition, (New York: HarperCollins, 1997)). Thus it is no longer

impossible for priestly material to have been known to Nephi.

Yes,

the final redaction to combine the distinct older documents into the

Torah as we know it apparently came after the Exile and was probably

done by Ezra, but the Exodus story is an ancient one that was widely

known among the Jews of Nephi’s day. Details of how it happened vary

among the hypothesized documents and within the OT of our day. Recently

Friedman has further explained why it’s a serious mistake to use the

Documentary Hypothesis and the alleged lack of archaeological evidence

for the Exodus to argue that the Exodus was fiction. See “The Exodus Is Not Fiction: An Interview With Richard Elliott Friedman,” Reform Judaism, Spring 2014, http://www.reformjudaism.org/exodus-not-fiction.

He sees evidence that the Exodus in some way was a historical event and

points to evidence in support of some aspects of the concept, though he

argues it probably happened to a much smaller group of Hebrews (perhaps

the Levites only).

As I’ll also show that the references

in the Book of Mormon to themes in the Pentateuch lack the major unique

elements that characterize P (the importance of central sacrifices, an emphasis on Aaron, etc.), so the case for Nephi relying on material

unique to P may be questioned. On the other hand, some LDS scholarship

suggests that the brass plates may have been a largely Elohist (E)

document, with strong influence from the Northern Kingdom, which is plausible given that the brass plates are a record associated with the tribe of Joseph.

The evidence from the Arabian Peninsula is not vaporized by a Documentary

Hypothesis death beam. It still counts as evidence, and indeed, the

evidence may be useful in helping us to make critical adjustments to our

theories of scriptural formation. If First Nephi has external evidence of

authenticity, then it gives us a precious lens into the world of the

Jews just before the Exile, allowing us to learn of a sacred record on

brass plates that was kept in reformed Egyptian. By examining and

inferring what was on the brass plates and what traditions Nephi and his

family had, either from the brass plates, oral tradition, or other

records, we can obtain precious data about ancient records, the

intrigues of priests, the corruption of scripture, and the preservation

of the Word of God in spite of all the human influences that get in the

way. If Nahom is authentic evidence, it’s more than just evidence to

help us understand the plausibility of the Book of Mormon; it may be a

vital step toward understanding the origins of the Old Testament and

testing various elements of the Documentary Hypothesis.

Too Biblical to Be Real?

RT’s

post at Faith Promoting Rumor leads up to his use of the Documentary

Hypothesis by first pointing out that Nephi’s parallels to Exodus are

suspicious.

The first problem that the apologetic

argument faces with regard to Nahom as an authentic ancient reference is

that the larger journey narrative recounted in 1 Nephi is for the most

part implausible as real history. The account contains many story

elements and language that indicate it originated as imaginative

mythological literature modeled along biblical patterns, whereas it

lacks evidence of certain details that we would expect to find if it

were in fact a realistic report of an Israelite family journeying from

Jerusalem through the deserts of Arabia.

This is not a

problem if one understands that Nephi is writing a sacred text, and that

he is likening the scriptures to their situation and creating a moral

parable from his journey that he sees, at least eventually, as a

divinely crafted parallel to the Exodus. In my opinion this fits what we

know of the ancient religious mindset. Types and paradigms of this kind

were vital and deliberate, and sometimes richly applied. Nephi is

writing sacred history and emphasizing the ways in which his story

follows a divine archetype. In fact, he’s retelling and probably

reshaping his story (not fabricating it!) to emphasize sacred themes in

much the same way that the authors of the Bible, according to biblical

scholars, may have adapted their writings to achieve specific purposes.

This does not make Nephi’s work a pious fraud, but a pious retelling or

pious redaction of his experience. This should not come as a surprise,

for he explains that on the small plates that he is engraving, his

purpose is to focus on spiritual things, not mundane details that are

more likely to be found on the related but more extensive and more

secular large plates.

Recognizing and emphasizing

parallels to biblical themes does not render the story fake, no more

than if your pioneer grandmother used Exodus themes when she retold her

story fleeing enemy mobs by a dry crossing the (frozen) Mississippi

River as they fled Nauvoo on the way to the promised land across the

plains. The miracle of the quails and many other aspects of the pioneer

journeys to Zion could be written with extensive references to Exodus

without rendering them non-historical, no matter how much detail was

left out in the process.

Given the significance of

Exodus to the Hebrews, I think a sacred journey to the Promised Land

that didn’t consider parallels to Exodus would raise even more serious

questions than RT raises (unless he’s completely right in his most

serious argument based on the Documentary Hypothesis, which we’ll

address below).

As modern scholars have dug into

Nephi’s writings, they have found that Nephi’s interweaving of key

Hebraic themes is pervasive, subtle, and skillful, even to the point of

making clever Hebraic word plays (Nahom included) and crafting Semitic

poetry in ways that make it difficult to imagine young Joseph Smith

doing this, whether using loads of available books to guide him in

slowly crafting a thoroughly-researched manuscript or just dictating the

text on the fly, as multiple witnesses attest. The interwoven biblical

themes in his text are crafted so well, that it should, in my view,

count as evidence for ancient origins rather than modern. Consider, for

example, the deliberate ways in which his slaying of Laban is patterned

after David and Goliath, serving as an important basis for his

descendants in recognizing the validity of Nephi’s claim to be the

rightful ruler of the people. This is explained in detail in Ben

McGuire’s “Nephi and Goliath: A Reappraisal of the Use of the Old Testament in First Nephi,”

which also does much to explain why Nephi’s focus on preparing a sacred

text is not aimed at providing the kind of details RT is asking for.

(It also provides some evidence relevant to the Documentary Hypothesis

and the relationship between biblical sources and the brass plates that

Nephi had.)

Exploring Nephi’s use of biblical allusions

and themes in his writing, including clever Hebraic word plays, is a

fertile field for ongoing scholarship and discovery, not a trivial

exposé of poor modern authorship from young Joseph. There is depth and

subtlety here. Yes, the story is heavily grounded in biblical

themes–not because it never happened, but because it happened to a

Hebrew family steeped in the ways of Hebrew writers as they crafted a

sacred text that not only would serve to help bring people to the

Messiah, but would also serve other purposes such as reinforcing the

basis of their political rights.

However, RT has a

significant point that may overthrow my reasoning above, for if he is

right, there’s no way that a real Nephi could have written about the

Exodus. Let’s explore RT’s most potent weapon as he unleashes the

Documentary Hypothesis against the Arabian Peninsula evidence.

The Documentary Hypothesis vs. Nephi

Here is what I consider to be the most serious attack RT makes in his post:

[P]erhaps

most damagingly, the allusions and references to the book of Exodus in

the BoM show that the form of the narrative it presumes corresponds to

that found in the Bible, combining both non-priestly (non-P) and

priestly (P) material. As is well known, one of the more significant

conclusions of two centuries of biblical scholarship is that the story

of the Exodus is actually a product of multiple literary sources/strands

that were developed and combined over time, including a non-P source

(sometimes divided into separate Yahwist and Elohist sources or early

non-P and late non-P strands) and a P source that covered similar

material but had distinctive theological emphases and content as well.

Although many scholars believe that some of the non-P material may date

to the pre-exilic or monarchic period, the P source is at the earliest

exilic and more likely from the post-exilic/Persian period. The P source

would also by necessity have been composed before it and non-P were

combined together into one continuous Torah narrative, meaning that the

project to conflate the sources would have occurred even later during

the Persian period. So in direct opposition to what we would expect if

the BoM were ancient, the author of 1 Nephi seems to have known and made

use of an Exodus that contained both P and Non-P.

- The

knowledge of P is reflected in 1 Ne 3:3 (Gen 46:8-27; Ex 6:14-25); 4:2

(Ex 14:21-22); 16:19-20 (Ex 16:2-3); 17:7-8 (Exodus 25:8-9); 17:14 (Ex

6:7-8); 17:20 (Ex 16:3); 17:26-27, 50 (Ex 14:21-22); 18:1-2 (Ex

35:30-33).

- The knowledge of non-P in 1 Ne 1:6 (Ex 3:2); 2:6 (Ex

3:18; 8:27; 15:22); 2:7 (Ex 3:12, 18; 8:27; 17:15; 18:12); 2:11-12 (Ex

14:11-12); 2:18-24 (Ex 15:26); 3:13, 24-25 (Ex 4:21-23; 5:1-2, 6; 7:20;

8:1, 8, 25; 9:27); 3:29-30 (Ex 14:19-20); 5:5-8 (Ex. 18:9-11); 6:4 (Ex

3:6, 15; 4:5); 16:10, 26-29 (Num 21:8-9); 16:35-36 (Num 14:1-4); 16:37

(Ex 2:14; Num 16:1-3, 13-14); 17:13 (Ex 13:21); 18:9 (Ex 32:4-6; Ex

32:18-19).The extensive borrowing and

revisioning of the Exodus story in the BoM is thus most easily

reconciled with a modern origin for the narrative. Not only would this

provide a setting for such an all-inclusive revisioning to have taken

place, but it would explain why various aspects of the borrowing do not

reflect the social, intellectual, and literary world of ancient Israel.

That

certainly sounds devastating. If the cumulative weight of two centuries

of scholarship compels us to recognize that the Jews of 600 BC were not

familiar with the Exodus story, at least as we know it, then how could Nephi refer to it? While parts of

the book of Exodus from the non-P source may have been available before

the Exile, the significant portions attributed to the a priestly source

(P) were, according to RT, not around before the Exile. The two were not

combined until long after the Exile, so there is no way Nephi could

have used both.

Here RT is appealing to what is known

as the Documentary Hypothesis. This is a vital aspect of biblical

studies in which scholars, after even more than two centuries of

exploring the details of the Old Testament, have determined with a great

deal of plausible arguments that the Bible as we know it has been

crafted from at least four original sources written by different people

or groups in different places and times, then finally edited together

into the complex and sometimes contradictory Masoretic text that we now

have.

The now classical Documentary Hypothesis owes

much to Julius Wellhausen, a scholar who over a century ago pulled

together a great deal of previous scholarship and painted a compelling

picture that attempted to reverse engineer the making of the Bible,

explaining how different styles of language, different names of deity,

and different versions of the same story were patched together in the

Old Testament. He concluded that there were 4 original documents behind

the Pentateuch, each known by a single letter:

- J,

the Yahwist source (J is the first letter of Yahweh when written in

German), written around 950 BCE in the southern Kingdom of Judah, so

named because it tends to use Yahweh (Jehovah) as the name for God. (Friedman puts J between 848 and 722 B.C.) - E,

the Elohist source (E) : written c. 850 BCE in the northern Kingdom of

Israel, so named because it prefers to use “Elohim” as the name for God. (Friedman puts E somewhere from 922 to 722 B.C.) - D,

the Deuteronomist source (essentially the book of Deuteronomy) :

written c. 600 BCE in Jerusalem during a period of religious reform

(Josiah’s era). - P, the Priestly source: written c. 500 BCE by Kohanim (Jewish priests) in exile in Babylon. (As we will see, Wellhausen’s dating of P is based on several serious errors, according to Friedman.)

Many

scholars concluded that J and E were combined prior to the Exile and

were available as a redacted document known to scholars today as JE. In

theory, JE and D could have been known to Nephi, but RT argues that P

was not, and the combination of these documents was not available until

even later, after the Exile, by someone such as Ezra.

So if Nephi relies on the Exodus story told in P, and P wasn’t written in his day, there may is a problem.

No Exodus story in 600 BC = no real Nephi = who cares about Nahom and Bountiful, right?

Does the Documentary Hypothesis trump Nahom? Does it trump any and all Book of Mormon evidence?

Some

fellow Christians and some devout Jews at this point may wish to jump

in and help me by pointing out that the Documentary Hypothesis is a

theory in flux, filled with weak spots, devoid of extrinsic evidence

outside of internal textual analysis (i.e., no manuscript for any of the

individual sources has ever been found), and the target of many

arguments against it. But I’m not going to focus on the arguments

against the basic concept of the Documentary Hypothesis. I think it has

significant merit and needs to be considered, tentatively and

cautiously. In my view, it cannot be easily dismissed and may have a lot

to offer.

For those who value the scholarship behind

the Documentary Hypothesis, in spite of many unknowns, here’s the most

critical factor that RT is missing in his misapplication of the

Documentary Hypothesis: There is significant, credible evidence that

Wellhausen was seriously wrong in dating of P. The crafting of the P

manuscript, according to one of the world’s foremost scholars conducting

research in the details related to the Documentary Hypothesis, occurred

before the Exile, probably in Hezekiah’s era, before Josiah and before

Nephi. That scholar is Richard Elliott Friedman, who was a student of

Frank Moore Cross at Harvard, where he obtained his ThD. He is now the

Ann and Jay Davis Professor of Jewish Studies at the University of

Georgia and the Katzin Professor of Jewish Civilization Emeritus of the

University of California, San Diego, and was a visiting fellow at

Cambridge and Oxford and a Senior Fellow of the American Schools of

Oriental Research in Jerusalem. He is the author of seven books,

including the bestselling Who Wrote the Bible? and Commentary on the Torah.

He participated in the City of David Project archaeological excavations

of biblical Jerusalem and served as a consultant for PBS’s Nova: “The

People of the Covenant: The Origins of Ancient Israel and the Emergence

of Judaism” and A&E’s “Who Wrote the Bible?” and “Mysteries of the

Bible.”

Let’s consider the credible case made by Richard Elliott Friedman in his award-winning book, Who Wrote the Bible?

He identifies three serious mistakes that led Wellhausen and others to place P after the Exile. These were:

- The idea that the prophets (e.g., Jeremiah and Ezekiel) do not ever cite material from P.

- The

notion that the Tabernacle was not historical but a fiction created

after the Exile and inserted into P to provide a rational in the words

of Moses for the centrality of the Temple, which is never mentioned in

the Pentateuch. The fabricated tabernacle, according to Wellhausen, was

created in P to provide an ancient rationale for the Temple. - The

idea that P takes the centralization of worship for granted, as if it

were written in a time when there was no doubt that centralization was

the norm (i.e., after the Exile).

Friedman shows

how each of these were serious mistakes. Jeremiah and Ezekiel actually

do cite P material several times, showing that P existed before the

Exile. For example, Ezekiel 5 and 6 provide a lawsuit of sorts against Israel for not keeping their covenant with God, and the covenant referred to is detailed in Leviticus 26, a P source which Ezekiel relies on with many nearly verbatim passages. Ezekiel and Jeremiah use other portions of P as well (e.g., Ezekiel draws upon P elements of the Exodus narrative).

The evidence that made the Tabernacle, in Wellhausen’s view, seem like a conveniently

crafted half-scale model of the Second Temple was based on considering

the dimensions of the First Temple, not the second, and Wellhausen got other things

wrong in his analysis. Friedman points to a strong strand of textual evidence showing

that the Tabernacle was historical and, in fact, was stored in the First

Temple. Finally, Friedman points out that P sources repeatedly teach

centralization of worship at the tabernacle, something Wellhausen

missed.

Further evidence for Friedman’s early dating of P include analysis from Professor Avi Hurvitz of Hebrew University in Jerusalem showing that the language of P is an earlier stage of biblical Hebrew than Ezekiel. Since that 1982 publication, at least five other scholar have published linguistic evidence that P’s version of Hebrew comes from before the Exile to Babylon.

Finally, Friedman points out that Wellhausen’s theory of P being a post-exilic document and a pious fraud to justify the second Temple does not fit the content of P. P emphasizes the ark, the tablets, cherubs, and the Urim and Thummim–relics that were completely absent from the second Temple. “Why would a second Temple priest, composing a pious-fraud document, emphasize the very elements of the Tabernacles the the second Temple did not have?”

Friedman notes that the person who wrote P “placed the Tabernacle at the center of Israel’s religious life, back as far as Moses, and forever into the future.” This person had to be living before “They cast your Temple into the fire; They profaned your name’s Tabernacle to the ground” (Psalm 74:7, one of several passages alluding to the Tabernacle having been kept in the first Temple).

The data related to the content and the

purposes behind the priestly source led Friedman to not only conclude

that P was pre-exilic, but that it could be dated specifically to the

time of King Hezekiah. That leaves plenty of time for P material to

become available to Nephi, or even be recorded on the brass plates (though

Sorenson notes that Book of Mormon seems much more closely aligned with

the Elohist document).

For further reference, a detailed, scholarly book on the Documentary Hypothesis written for an LDS audience is David E. Bokovoy’s Authoring the Old Testament: Genesis-Deuteronomy (Part One) along with Part Two

(the paperback is just one volume; it’s split in two for Kindle readers). Bokovoy generally accepts the dating of Friedman, and adds many insights about the Mesopotamian sources that appear to have been used by those crafting the various sources. He also explores implications of the Documentary Hypothesis for Latter-day Saints, observing the Book of Mormon account shows a process very similar to the Documentary Hypothesis in play, and also noting that Joseph Smith’s concerns about the corruption of ancient scripture and the missing or altered elements in the Bible is consistent with what we can observe happening in the Bible text through the tools of Higher Criticism.

Some of Bokovoy’s views may be troubling to some LDS readers, such as his view that the Book of Moses given by Joseph Smith could not possibly have come from Moses. Regarding the Book of Mormon, while he sees some merit in John Sorenson’s hypothesis about the dominance of E in the brass plates and the Book of Mormon, he points out a number of places where P and D are relied on, such as references to the Creation story and the Flood. He leans toward Blake Ostler’s “expansion theory” for the Book of Mormon, arguing that Joseph may have taken a simpler ancient text and expanded it, enriching it with detailed prophecies about Christ that the Nephites might not have actually had. I struggle with that notion, but admire his thorough scholarship and clear writing, and feel this work is a valuable one for serious students of the Bible to consider.

Another thoughtful article for LDS readers on the Documentary Hypothesis is Kevin L. Barney, “Reflections on the Documentary Hypothesis,” Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 33 No. 1, Spring 2000: 57-99.

Must Bible Believers Fear the Documentary Hypothesis? Insights from the Book of Mormon

The

Documentary Hypothesis, while it has weaknesses and many detractors,

must be recognized as having a great deal of serious scholarship behind

it. But many people who believe in the Bible as the word of God may feel

threatened when they encounter this. After all, it can be quite

disturbing to suddenly learn that Moses apparently didn’t write the

Books of Moses (that is, the Books of Moses as we now have them–the

Hypothesis does not prevent him from having written or having passed

sacred history on through oral traditions). To be told that the great

stories that are the foundation of the Bible might have been cobbled

together from multiple conflicting sources can turn the miraculous word

of God into a much-more imperfect, man-made work. Can that even be

trusted as scripture anymore?

The editorial processes

that are being uncovered in the Bible actually reflect some of the Book

of Mormon’s warning that the record of the Jews in our day, the Bible,

would be heavily edited and have significant losses. That complex

editorial process is also what Book of Mormon readers see happening

right before their eyes as they observed the many records that Mormon

has cobbled together from records in Hebrew, reformed Hebrew, and at

least one Jaredite language, records which he tweaked, redacted, and

commented upon to give us the “crazy patchwork” record of the Book of

Mormon, which then went through further changes as it was translated

into English (or rather, a puzzling mix of pre-KJV Early Modern English

influences coupled with KJV English and some modern English–what these

various influences are and how and why they are there remains a hot

topic for research and speculation). To study the Book of Mormon

carefully is to unveil a complex combination of sources used by Mormon

in his work of redaction. Still today, the more we learn about the Book

of Mormon and its translation, the more complex and varied it becomes.

Surely we should be able to be comfortable with a complex and heavily

edited Bible, especially when LDS scripture teaches us to expect heavy

human editing over the centuries of its transmission.

We

can see and recognize the hand of humans in each stage of the Book of

Mormon’s creation: first from the hand of Mormon, including Mormon’s

editing, his concern about errors that he may be making unintentionally

and because of the difficulty of working with the written language (not

to mention the challenge of writing on metal plates, devoid of a

backspace key–it looks like he may have used “or” instead), his

recognition that his limited writing abilities would lead to mocking by

future readers, etc. Then we have the hand or tongue of Joseph

translating it in a process of steady oral dictation without reference

to other documents, giving us text with clear signatures from Early

Modern English that really should not be there. In this process, we also

see the human touch of Oliver’s hand and the hand of other scribes who

wrote down what they heard but sometime made obvious errors, many of

which they caught and corrected. We can see and retrace the oral process

of hearing and writing as we examine the Original Manuscript of the

Book of Mormon, a divine fruit with clear human influence. Then we have

the human influence of preparing a printer’s manuscript, and the

influence of the printer’s hand in adding punctuation and making other

changes and sometimes some clear mistakes in printing the manuscript.

Then there are other editorial changes, some from Joseph, some from

Parley P. Pratt and others, bringing us to modern editions such as the

1981 Book of Mormon in which many attempts were made to correct some of

the usually minor mistakes that had crept into the text. And naturally,

when this text is translated into German, Chinese, or Navajo, numerous

new human influences enter into the sacred text. A divine text becomes

“divine plus,” or maybe “divine minus.” We cannot separate human

influences from sacred records, and the sacred text of the Book of

Mormon makes that remarkably clear, while also serving as a divine

record that, in spite of errors, can be called the “most correct book.”

It is a remarkable witness of Jesus Christ and of the reality of the

Restoration.

If we can accept the Book of Mormon in

spite of its human influences, we should be able to benefit from the

divine richness of the Bible that remains in spite of questions,

problems, and abundant human influences. We must temper our expectations

and remain flexible, recognizing that some things we thought we

understood may not necessarily be that way. But that same recognition

needs to be applied to the decrees of scholars: what is declared as fact

today may not be so tomorrow, and in my view, it would be a shame to

abandon God in the process because of what may one day become an

abandoned theory of humans.

In an age when the

Documentary Hypothesis is shattering the faith of some Jews and

Christians, the true but patchwork and human-smudged Book of Mormon may

be just the thing to bear witness of the core truths of the Bible. The

Book of Mormon may help remind us that the fingerprints of Deity are

still in those ancient records in spite of many human smudges. The Book

of Mormon may be just the thing, that is, if it in turn can withstand

the fierce assault of the Documentary Hypothesis on its own integrity,

for the Book of Mormon relies heavily on the Bible in ways that allow

Documentary Hypothesis advocates to also challenge the historicity of

the Book of Mormon.

The apparent consensus among the

majority on the classical Documentary Hypothesis may not be as firm as

RT implies. While I think many aspects of it may be valid, there is

tremendous diversity among believers of the Documentary Hypothesis, and a

significant body of serious scholars and students of the Bible who find

it inadequate. It must be treated with both respect and a dose of

caution.

On the other hand, Latter-day Saints are in a

surprisingly good position with respect to some of the findings behind the

Documentary Hypothesis. We can readily recognize that the creation of

scripture can involve multiple documents from many time periods and

sources that are combined into a patchwork of sorts as they are redacted

by one or more editors, for that is the very process taking place

before our eyes in the Book of Mormon, with the important and

fascinating distinction that Mormon often allows us to see or infer what

source material he is drawing upon. In the Book of Mormon, we can see a

scriptural text being redacted before our very eyes, even to the point

of having its own version of doublets, of stories told twice or more,

especially with the inspired inclusion of the small plates that

apparently puzzled Mormon because he recognized he was providing a large

amount of duplicated information.

The complexity and

textual sophistication of the Book of Mormon record is one that can help

us better appreciate the origins of the Bible. This is especially so

when we try to infer what was on the brass plates and how their content

might differ from today’s Masoretic text. John Sorenson, for example,

wrote favorably of the Documentary Hypothesis (“The ‘Brass Plates’ and Biblical Scholarship,” Dialog,

vol. 10, no. 4, pp. 31-39). He proposed that the brass plates may have

largely been related to E, the Elohist document. Evidence for that

proposal includes the heavy use of “Lord” instead of “Jehovah” among the

names for deity in the Book of Mormon: apart from a quotation from

Isaiah, “Jehovah” only occurs once, in the last verse of the book.

Further evidence includes the many prophets from the Northern Kingdom

that are quoted.

Sorenson’s hypothesis seems to fit in light of the broad characteristics of the 4 sources. According to Friedman in Who Wrote the Bible?, E challenges the religious establishment in Judah with its priests from the family of Aaron, favors Moses over Aaron, favors prophets such as Samuel over priests (the word “prophet” never occurs in J and occurs only once in P!), and favors Ephraim, and was probably written by a Levite priest from Shiloh which is in Ephraim, from whence Samuel came. The author may have considered himself to be a descendent of Moses. On the other hand, J favors the religious establishment in Jerusalem, favors Aaron over Moses, and never mentions the Tabernacle, which was originally associated with the city of Shiloh, source of the branch of Levite priests that were considered a threat to the priests descended from Aaron in control in Judah.

Other characteristics of note:

- E contains three chapters of law, which is what we expect in a document written by a priest or priests, while J does not. 1 Nephi 1:15-16 states that the law of Moses was recorded on the brass plates.

- The bronze serpent is an important symbol in E and is associated with a great miracle performed by Moses. E is the only source for that story, which also plays an important role in the Book of Mormon. The P document, on the other hand, praises Hezekiah for destroying the bronze serpent, viewed as a tool of idolatry.

- E and D refer to the mountain where Moses received his revelation as Horeb, while J and P call it Sinai. While Nephi may make allusions to Moses’ experience on the mount as he also obtains revelation on mountains, Sinai is mentioned by name once by Abinadi in Mosiah 12:33, which does not strengthen Sorenson’s hypothesis. (Of course, one could argue that whatever it was called in the original Book of Mormon text, Sinai would be a plausible “translation” to make the reference clear with how modern readers know the name of that mountain.) Consistent with Sorenson, the revelation at Horeb/Sinai was important in E but less so in J, which emphasized the covenant to the patriarchs and the House of David over the covenant at Sinai.

- The ark of the covenant does not appear in E (nor in the Book of Mormon) and the Tabernacle does not appear in J (in the Book of Mormon, the word tabernacle, possibly alluding to the Tabernacle of the Pentateuch, occurs in a quotation in of Isaiah 4:6 in 2 Nephi 14).

- E has no Creation story and no Flood story, at least not that was compiled into the Masoretic text. The brass plates discuss the Creation and the Flood.

- When Moses strikes a stone at Meribah and brings forth water from the rock for thirsty Israel, this is a positive miracle in E, but the story is repeated in the Bible from P and there becomes negative, somehow an act of disobedience that dooms Moses to die before entering the promised land. The Book of Mormon mentions that miracle in a positive light (1 Nephi 17:24). Further, the Book of Mormon is so positive about Moses that even his apparent death may have actually have been the miracle of being translated by the Lord (Alma 45:19), in apparent disagreement with the OT but also alluded to by Josephus.

The sharp differences between J and E and between all four sources, for that matter, have led some to reject the Bible and their faith entirely. Friedman explains repeatedly that differences in texts that may reflect different interests and perspectives of those shaping the records do not imply that the basic events being treated are all fiction. It is important to also recognize what is shared between these sources. Of J and E, he writes:

The two versions, nonetheless, would be just that: versions, not completely unrelated works. They would still be drawing upon a common treasury of history and tradition because Israel and Judah had once been one united people, and in many ways they still were. They shared traditions of a divine promise to their ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. They shared traditions of having been slaves in Egypt, of an exodus from Egypt led by a man named Moses, of an extraordinary revelation at a mountain in the wilderness, and of years of wandering before settling in the promised land. Neither author was free to make up—or interested in making up—a completely new, fictional portrayal of history.

In style as well, once one version was established as a document bearing sacred national traditions, the author of the second, alternate version might well have consciously (or perhaps even unconsciously) decided to imitate its style. If the style of the first had come to be accepted in people’s minds as the proper, formal, familiar language of recounting sacred tradition in that period, it would be in the second version’s interest to preserve that manner of expression….

Another possible explanation for the stylistic similarity of J and E is that, rather than J’s being based on E or E’s being based on J, both may have been based on a common source that was prior to them. That is, there may have been an old, traditional cycle of stories about the patriarchs, exodus, etc. which both the authors of J and E used as a basis for their works. Such an original cycle would have been either written or an orally passed-down collection. In either case, once the kingdoms of Israel and Judah were established, the authors of E and J each adapted the collection to their respective concerns and purposes. [emphasis mine]

There may be corrupted, altered, or fabricated details between the versions, but there is a core of ancient experience behind these accounts, or even other ancient records, a possibility Friedman also acknowledges.

As an aside, an interesting aspect of the brass plates is that they contained many prophecies of Jeremiah (1 Nephi 5:13) and other prophets. Jeremiah or his scribe is identified by Friedman as the author of Deuteronomy (D), both Dtr1 (the first version of D, before the Exile) and a much smaller body of adjustments made after the Exile, known as Dtr2. If Jeremiah’s writings were on the brass plates, Dtr1 could easily have been there, too. Thus, information from all five of the “Books of Moses” may have been present on the brass plates, either from a version of E plus D (Dtr1) and prophetic writings, or an older, more complete document related to E plus D and prophetic writings. If so, Nephi’s reference to the “five books of Moses” (1 Nephi 5:11) found in the brass plates could be reasonable. The information may not have been neatly organized in five books, and instead he may have called it the Torah of Moses, with “five books of Moses” being a reasonable translation for modern readers. Or perhaps there were five distinct groupings. Bible scholarship here may cause us to question whether this phrase was Nephi’s or a translator, but questions raised by the Book of Mormon can also help us modify our understanding of Bible origins.

Ultimately, the Book of Mormon may be exactly what

the world of Bible scholars and students need to re-evaluate, revise,

and perhaps even validate theories on the origin of scripture. If Nephi

uses something from P, for example, and we have evidence for the

authenticity of Nephi’s record, that’s the kind of evidence that ought

to help us push back on any theories that require P to be post-exilic.

When RT applies a popular theory to exclude Book of Mormon evidence, he

may actually have things quite backwards. The evidence, if it holds, may

be a useful tool in the end for revising weak spots in the theory. Of course, the translated text of the Book of Mormon may not always accurately reflect what was on the gold plates and/or brass plates due to artifacts of translation and even “expansion” by Joseph Smith, as Blake Ostler has proposed. This is where work pointing to frequent evidence of at least some tight control in the translation of the text may be especially helpful and relevant (e.g., Hebraisms and Hebraic poetry, names, and even the puzzling and controversial issue of Early Modern English influences in the text that are independent of or distinct from the patterns of KJV language).

There is much more research to be done and much more to understand. I suspect that as we seek to better extract what was on the brass plates and to relate that material to Bible scholarship, we may learn more about both the Book of Mormon and the Bible.

Are

You Saying that an Alleged Sacred Text Engraved on Precious Metal

around 600 BC Challenges Some Aspects of the Documentary Hypothesis?

That’s

exactly what I’m saying. Well, almost exactly, if you’ll kindly change

one word in that question: delete alleged, because the engraved sacred

text is NOT alleged, but real, tangible, and has now been scientifically

studied by scholars who have confirmed its date, its reality, and its

relevance. Oh, I’m not talking about those engravings, not the

gold plates of Nephi nor the brass plates he brought to the New World.

I’m talking about the much smaller silver plates, or rather, two small

silver scrolls that were found near Jerusalem that have been carefully

examined and dated to pre-exilic times around 600 BC, which quote from a

passage in Numbers that is part of the P document. This archaeological

find further destroys the argument that P was a late creation after or

during the Exile. See:

- “Bible Texts on Silver Amulets Dated to First Temple Period,” Haaretz.com, Sept. 19, 2004.

- “Ketef Hinnom,” Wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ketef_Hinnom.

- Stephen Caesar, “The Blessing of the Silver Scrolls, ” BibleArchaeology.org, 2010.

If

finding P material on tiny silver plates from Nephi’s day helps to

overturn some aspects of the “two centuries of scholarship” behind

previous theories about the Pentateuch, we might do well to also

consider the possibility that Nephi’s writings and allusions to Exodus

themes, including allusions to possible P material, may be useful in

helping us recalibrate the tools used in establishing various versions

of the Documentary Hypothesis or competing theories of Bible origins.

As

mentioned above, John Sorenson has laid a foundation in evaluating the

Book of Mormon in light of the Documentary Hypothesis by pointing out

the strong Elohist (E) elements of the Book of Mormon text. I suggest

that there are many more veins to explore, using some of the techniques

applied by Bible scholars in exploring the OT test. The Book of Mormon

is complicated by the lack of the original gold plates to explore, but

we do have the translated text, including the richness of Royal

Skousen’s Earliest Text of the Book of Mormon. There are

complex issues to explore, such as the complexities of the dictated

language with its strange reliance on a form of English, long thought to

just be Joseph’s bad grammar, now being shown to contain a strong vein

of Early Modern English predating the KJV. Yet there are also apparent

Hebraisms that have survived translation, many Hebraic word plays that

can be reconstructed. There is also the translation factor of a strong

preference for KJV phrases to be used, apparently when appropriate, even

when those phrases come from the New Testament. The Book of Mormon is

cast into the familiar language of scripture in a complex, subtle, and

pervasive way, yet loaded with grammatical structures that predate the

KJV. In addition, there are the complexities of numerous documents and

authors contributing to the Book of Mormon, whose individual styles also

seem to survive translation. Pulling out the various signals that give

us the Book of Mormon and extracting more detailed information about

what may have been on the brass plates and what Nephi and others knew

and said in 600 BC and later, is an opportunity for further scholarship

that I trust will be fruitful.

A Lack of P Influence in the Book of Mormon, and Is That a Problem or Strength?

Sorenson’s hypothesis that the brass plates were influenced by E seems reasonable given that the plates were from the tribe of Joseph and would be expected to have some of the same influences that the northern E appears to have. Likewise, even though P dominates the Torah, providing over 50% of it and a larger portion of Exodus, the Book of Mormon in my tentative view appears to lack the major characteristics that have helped scholars identify P. These uniquely P elements include an emphasis on the need for priests descended from Aaron and a favoring of Aaron over Moses, extensive details on the construction of the tabernacle, the concept of central sacrifices and worship, the idea that no sacrifice was practiced before the revelation at Sinai, the exalted status of Aaron and the priesthood, and the use of the divine title El Shaddai prior to Sinai.

In P, God is also less anthropomorphic and more ethereal or cosmic. There are no angels. The emphasis is on the law and the role of the official Aaronid priests, who are essential for the purity and worship of the people. P also serves to establish the income of priests, ensuring that sacrifices are made under their control which gives them food, and that tithing is paid through them. In describing some of the characteristics of the priestly source, Friedman in Who Wrote the Bible? says this:

The issue is not just sacrifice. For the author of P, it is the larger principle that the consecrated priests are the only intermediaries between humans and God. In the P versions of the stories, there are no angels. There are no talking animals. There are no dreams. Even the word “prophet” does not occur in P except once, and there it refers to Aaron. In P there are no blatant anthropomorphisms. In JE, God walks in the garden of Eden, God personally makes Adam’s and Eve’s clothes, personally closes Noah’s ark, smells Noah’s sacrifice, wrestles with Jacob, and speaks to Moses out of the burning bush. None of these things are in P. In JE, God personally speaks the Ten Commandments out loud from the heavens over Sinai. In P he does not. P depicts Yahweh as more cosmic, less personal, than in JE.

This all seems to contrast with the Book of Mormon, where God is anthropomorphic and is seen and heard by men, where angels play a vital role throughout the text, where religion is not centralized and even a temple (more than one, in fact) can be built without scandal in a new land (as the Jews at Elephantine, Egypt did).

While the Book of Mormon mentions Moses over 30 times, always in a positive light (unlike P), the treatment of his brother Aaron is quite unlike P. While the Book of Mormon features the name of Aaron as a name, including the name of a small city, the Aaron of the Old Testament is never mentioned, nor is the Aaronic Priesthood, which seems like a puzzling omission if Joseph Smith was fabricating the Book of Mormon to pave the way for a Church that has both the Melchizedek and Aaronic priesthoods. Priests are ordained, but there is no requirement that they be descended from Aaron or anyone else, it seems; even Lamanites can become priests (Alma 23:4) and prophets. The priests of the Book of Mormon are expressly unpaid (Alma 1:26), having to labor with their own hands, in strong contrast to P. They are ordained to teach and serve, not to live off the labors of the people–with the notable exception of the wicked priests of King Noah, who show some of the same blindness and corruption that the priests of Jerusalem did in Lehi’s day.

Critics have complained that the Book of Mormon is far too unlike the Bible (or rather, unlike P) by failing to emphasize sacrificial rituals (though sacrifice certainly was part of their worship, as we learn in a mere two or three verses, not expanses of P-like text as some critics require). In fact, a number of common complaints about the Book of Mormon’s contradicting the Bible or being too unbiblical really are complaints that the Book of Mormon is not following P. The Documentary Hypothesis may helps us better appreciate why that weakness may be a strength of the Book of Mormon, or at least an intriguing, plausible feature worthy of further study.

RT complains that the Book of Mormon is too biblical in drawing upon the Exodus so thoroughly, though I would argue that this is actually a hallmark of the ancient Hebrew world and not a basis for denying the historicity of a pivotal event retold with themes from sacred archetypes. Contra RT, other critics deride the Book of Mormon for being not biblical enough, for failing to show the importance of centralized worship, for thinking that a temple could be built outside of Jerusalem, for not having complex sacrificial rituals established under the order of an elite group of Levites only, etc., but these are complains about the relative unimportance of P in the Book of Mormon, which actually makes sense if the Nephites have been heavily influenced by a northern kingdom E-like text and their forefathers were at odds with the established priests in Jerusalem in Lehi’s day.

A Suggested Update for RT

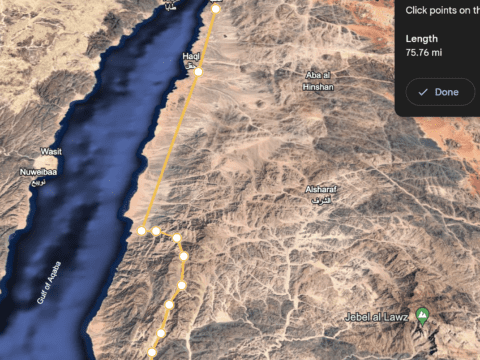

Getting back to the issue of Nahom, in

his blog post, RT admits that the south-southwest direction, the

description of fertile regions, turning east, etc., suggest a realistic

trip. I love the way he sums it up:

In my opinion, the

most plausible detail provided in the narrative of 1 Nephi 1-18 is the

description of the general route followed by Lehi on his way through

Arabia to the coastal location of Bountiful. From all the reporting of

events that occurs in this part of the BoM (setting aside the reference

to Nahom), the few comments that clarify that the party of Lehi traveled

to the Red Sea (1 Ne 2:5-6) and then moved along the Red Sea in a

south-southeast direction down the western side of the Arabian peninsula

(1 Ne 16:13), “keeping in the most fertile parts of the wilderness,

which were in the borders near the Red Sea” (1 Ne 16:14), and then

turning east before reaching the coast of Irreantum (1 Ne 17:1, 5) seem

to represent informational detail most certainly rooted in real world

geography. That is to say, the route appears to accurately account for

the shape of the Arabian Peninsula in relation to the Red Sea and

Arabian Sea and further agrees in a general way with what we know about

the topography of the region and where cross-country travel was most

practicable therein. Some of the more “fertile” parts of Arabia are

indeed in the high western zones and foothills of the Hijaz, where the

climate is slightly more temperate and rare rainfall in the mountains

has contributed to the creation of oases on the eastern slopes that

sustain more diverse flora and fauna. For millennia this strip of land

“bordering the Red Sea” has enabled human transit and trade from north

to south and facilitated the development of overland roads. So for Lehi to have followed this general track is notable and [here we go!] in theory could lend support to the assumption that the author of the account was trying to depict real history. [emphasis mine]

Hmm,

plausible directions and description for going from Jerusalem to

Bountiful–a previously mocked and unknown place that now has an

excellent and plausible candidate nearly due east of Nahom–all amount

to a general track that is “notable.” OK, at least we have an

admission that this achievement is notable. [Respecting a complaint from RT, my previously rather unfair and hyperbolic paraphrase of RT at this point has been deleted. The following paragraph is also a bit hyperbolic and tongue-in-cheek, but has been retained, though slightly modified. It is not a direct paraphrase of RT’s words, but a tongue-in-cheek attempt to show the humor that I see in RT’s treatment of the Arabian Peninsula evidence as merely “lend[ing] support to the assumption that the author was trying to depict real history.”]

This

is an important model for dealing with all future “evidence” that may

be uncovered by anthropologists, linguists, archaeologists, botanists,

biologists, and other experts. No matter how interesting it may seem,

how close and relevant it may appear to something in the text, the text

itself can always be dismissed in this manner: “the parallels in the

text to these external finds are notable and may, theoretically

speaking, lend support to the notion that Joseph Smith was sincerely

attempting to sound like he was trying to depict real

history.” Then we can point out the numerous details associated with the

finds that are not in the text. We can explain that the brief

references in the text that relate to the external evidences are brief,

vague, and ambiguous. And then we can argue that the

parallels or bulls-eyes actually miss the mark somewhat, for things in

real life are always more complicated than any brief account and, with a

sufficiently critical eye, we can always find

imperfection and fault with telegraphic descriptions of complicated

events.

He continues with on this descending trajectory:

However,

when we examine the description of Lehi’s route more closely it becomes

clear that its links with real world geography do not provide

unequivocal support for the historicity of the narrative. First, the

geographical information offered in the text is for the most part vague

and highly general in nature, limited mainly to general travel

directions and large bodies of water associated with macro-scale Arabian

geography, whereas more precise detail about the route is almost wholly

lacking, consisting of an occasional generic topographic feature such

as a nameless river and valley (1 Ne 2:6) or mountain (1 Ne 16:30;

17:7), or the mention of unspecified “fertile” areas near the Red Sea (1

Ne 16:14, 16). Because of this relative dearth of information about the

places visited by the Lehi group, the modern reader is presented with

the peculiarity that while he/she can easily grasp the general course of

their journey and has a rough idea of where it began and ended, almost

everything in between is nebulous and blurry. Not surprisingly,

researchers of the BoM have been unable to agree on the precise path

followed by Lehi in Arabia or even to identify a single site visited by

the group apart from Nahom.

I think that’s a stretch.

Potter’s identification of the Valley Lemuel and the River Laman, though

not without alternate candidates, has many compelling correspondences

in its favor. Remember, until he did the field work and found the river

in a plausible location, the impossibility of such a river existing in

Arabia was a major source of anti-Mormon mocking and a sure crutch for

any anti-testimony. But then suddenly, surprisingly, there is a

river–now a small stream after significant diversion of its waters for

other purposes–in a majestically walled valley that would provide

safety, shade, comfort, and even trees and fruit, with a river flowing

year-round (if that is what is meant by “continually,” though perhaps

Nephi just meant it was more than a dry wadi whose brief periodic water

flows depended on rain, unless they stayed there for several months or

more). Why does this not count as identifying a site visited by the

group apart from Nahom?

After reading Potter and Aston, I would reword RT’s claim as follows:

Original

from RT: “researchers of the BoM have been unable . . . even to

identify a single site visited by the group apart from Nahom.”

Revision:

“researchers of the BoM have been unable . . . even to identify a

single site visited by the group apart from Nahom, the Valley Lemuel and

the River Laman, the place Shazer, and, of course, the place

Bountiful.”

That little tweak would significantly

enhance the accuracy of the RT’s article. Of course, if that makes him

uncomfortable, he can add the caveat that “there is no consensus on

these places especially in light of alternate candidates that have been

proposed, for example, for the Valley Lemuel and the place Bountiful.”

That’s

what I think evidence needs to do: help us tweak or revise our

theories. Don’t let old paradigms bury new evidence before it’s even

been considered.

A Reminder

As a reminder, the Nahom

evidence is more than just a name on a map. Nahom is near the only place

where an eastward turn is possible away from the incense trails. Taking

that turn and going east brings you to an excellent candidate for a

place long thought to not exist, Bountiful. This is more than just a

“notable” attempt to sound like a real journey. Given the implausibility

of using anything short of modern tools such as satellite maps to

identify a Bountiful-like place on the eastern coast of the Arabian

Peninsula and to describe its location (“nearly due east”) relative to

an actual, accessible, place with a rare place name (Nahom/NHM), is it

more likely that the details of the First Nephi journey are best

explained as a description from someone who actually made the journey or

had first-hand knowledge of Arabia, as opposed to a farmer whose

R&D team managed to find a map of Arabia.?

Kent Brown offers this view in his chapter, “New Light from Arabia on Lehi’s Trail” in Echoes and Evidences of the Book of Mormon, one of many online books available at the Maxwell Institute.

Here is one except regarding the significance of the eastward turn in

Lehi’s journey, right after the group has buried Ishmael at the ancient

burial place of Nahom/Nehhem:

The most important

piece in this section concerns Nephi’s note that “we did travel nearly

eastward from that time forth,” after events at Nahom (1 Nephi 17:1).

This geographical notice is one of the few in Nephi’s narrative, and it

begs us to examine it. We first observe that, northwest of Marib, the

ancient capital of the Sabean kingdom of south Arabia, almost all roads

turn east, veering from the general north-south direction of the incense

trail. Moreover–and we emphasize this point–the eastward bend occurs

in the general area inhabited by the Nihm tribe. Joseph Smith could not

have known about this eastward turn in the main incense trail. No

source, ancient or contemporary, mentions it. Only a person who had

traveled either near or along the trail would know that it turned

eastward in this area. To be sure, the longest leg of the incense trail

ran basically north-south along the upland side of the mountains of

western Arabia (actually, from the north the trail held in a

south-southeast direction, as Nephi said). But after passing south of

Najran (modern Ukhdd, Saudi Arabia), both the main trail and several

shortcuts turned eastward, all leading to Shabwah, the chief staging

center for caravans in south Arabia. One spur of the trail continued

farther southward to Aden. But the traffic along this section was very

much less than that which went to and from Shabwah. The main trail and

its spurs ran eastward, matching Nephi’s description. Wells were there,

and authorities at Shabwah controlled the finest incense of the region

that was coming westward from Oman, both overland and by sea. It is the

only place along the incense trail where traffic ran east-west. Further,

ancient laws mandated where caravans were to carry incense and other

goods, keeping traffic to this east-west corridor. Neither Joseph Smith

nor anyone else in his society knew these facts. But Nephi did.

That’s

a remarkable feat, like so much about the miraculous and divine Book of

Mormon that is, like the Bible, still covered with human fingerprints.

In the many steps of engraving, editing, translating, and printing,

human hands have played a role. Understanding that process,

imperfections and all, can and should help us better understand the

Bible and its origins. And understanding the best scholarship on the

origins of the Bible may ultimately help us better understand the Book

of Mormon, but it’s a two-way street. Evidence needs to be considered both ways, not prematurely buried in spite of showing vigorous signs of life when it doesn’t fit the reigning paradigm.

Related resources:

Richard Elliott Friedman, “The Exodus Is Not Fiction: An Interview With Richard Elliott Friedman,” Reform Judaism, Spring 2014, http://www.reformjudaism.org/exodus-not-fiction

Richard Elliot Friedman, “Current Thought About the Documentary Hypothesis,” Introduction to Empirical Models for Biblical Criticism, Jeffrey Tigay, Editor.

Kevin L. Barney, “Reflections on the Documentary Hypothesis,” Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought, Vol. 33 No. 1, Spring 2000: 57-99.

“Bible Texts on Silver Amulets Dated to First Temple Period,” Haaretz.com, Sept. 19, 2004.

“Ketef Hinnom,” Wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ketef_Hinnom.

Stephen Caesar, “The Blessing of the Silver Scrolls, ” BibleArchaeology.org, 2010.

John Van Seters, ” Some remarks of the paper by Rolf Rendtorff, “What happened to the ‘Yahwist’?”, SBL Forum , n.p. [cited June 2006]. Online: http://sbl-site.org/Article.aspx?ArticleID=561.

Amazon description of John Van Seters, The Edited Bible: The Curious History of the “Editor” in Biblical Critism.

Konrad Schmid, “Genesis and the Moses Story,” BibleInterp.com, Oct. 2010, http://www.bibleinterp.com/articles/3gen357926.shtml.

Stephen Gabriel Rosenberg, “The Exodus: Does archaeology have a say?,” Jerusalem Post, April 4, 2014.

Kevin Christensen, comment on the Documentary Hypothesis, http://lds.net/forums/topic/8162-documentary-hypothesis-and-the-lds-position/page-2.

I have waited with interest for this post. Thanks.

I think that one of the beautiful things about The Book of Mormon, and therefore, "tender mercies" of the Lord is that believers and non-believers have good and substantial reasons for their conclusions. The believers' reasons will likely assist them in moving forward to build the kingdom of God and progress in developing Christ-like character. The non-believers' reasons may serve as mitigating factors when they meet Nephi, Jacob, and Moroni at the "pleasing bar".

Or pleading bar…

???

How many people are going to end up being at this "pleasing bar?" Won't they also have to stand before a "pleasing bar?" Will everyone have to wait until all those who are going to sit at the pleasing bar have first passed their own examinations, and can then rightfully take their place?

This starts to all break down into silliness.

God has given non-believers good and substantial reasons not to believe so that when they face their judgement, he can take it easy on them? Wow…

Yes, or pleading bar.

ETBU, It's really not that absurd, unless you think the principle taught in Alma 32:19 is absurd.

Is it really a "tender mercy" for God to provide "substantial reasons" for non-believers to come to their conclusions? Isn't that being deceptive?

"Hi,..I'm God. I am going to make a falsehood appear to be true so that those who believe the falsehood will be justified and therefore I won't have to really punish them."

Seriously? First of all, Satan is the one who is supposed to a lie appear to be truth.

I was being somewhat flippant in quoting "tender mercies" given its press.

I am not seeing why you are taking from my comment an assertion that it is God that provides the substantial reasons for non-believers to come to their conclusions.

I enjoyed this article a great deal Jeff. I didn't have the time to muster a response but I'm glad you did. I'm also a specialist in a different field which formed a larger reason why I demurred. My field is military history, and if I might humbly say, I know it just as well as RT knows his field. In all of my research the details I find make an incredibly strong case that the BoM is an ancient document. I read the BoM with that assumption or hypothesis, and I've never found one item or even a whiff of something that comes close to 19th century American warfare. (That includes comparisons with the Late War.) In fact, the more I study the BoM and secular sources I find rather amazing details. For example, a few days ago I discussed my findings from studying half a dozen insurgencies. I found the Gadianton Robbers in BoM are incredibly consistent with them down to rather obscure details: http://mormonwar.blogspot.com/2015/10/mesoamerican-anthology-gadianton-chapter.html

Thanks again Jeff. And good word play in the first paragraph. I got a good chuckle out of that.

I'm withholding judgment until RT posts part 3 of his series, in which he says he "will propose the hypothesis that Joseph Smith had seen and used a map of Arabia to construct his narrative about the exodus of Lehi’s family from Jerusalem."

I suppose I can imagine Nephi reshaping his story to highlight all the parallels with Exodus. I'm not sure I can take it seriously, though. If you've actually lived through dramatic events, and believe they were ordained by God, I really think you'd want to set them out exactly as they were, so that God's people can have your story as well as Moses's. The reshaping scenario makes most sense for later redactors, not for participants, and it still only makes sense if the accounts they are reshaping seemed less glorious, in their original version, than Exodus. So if you want to explain away why Nephi's account seems to echo Exodus too closely, then it seems to me you have to talk about later editors pumping up a blander original. The Book of Mormon would need its own Documentary Hypothesis.

The problem here, though, of course, is that once you doubt that the books of Nephi are Nephi's own un-retouched recollections, then it's hard to stop sliding down the slippery slope before ending up at Joseph Smith making everything up. Why would Nephi have been any better at making allusions and parallels between his story and Exodus than Joseph Smith would have been? Even if the P traditions were somewhat known before the Exile, it would seem that Smith knew Exodus better than Nephi could have.

A lot of weight seems to fall upon the arguments about how the English text of the Book of Mormon presents Hebraisms that Joseph Smith could not have constructed. Those arguments may have looked nice as further indications piled on top of a case that was already strong, but if the main case falls upon them to make, do they really hold up? I'm afraid I rather wonder. How many of them are tenuous? How many are obvious enough that Smith could hardly have missed faking them, if he were faking anything? Chiasmus, for instance, seems likely to be a rotten bough. And it's a lot easier than you might think to invent the trace of a Hebrew pun, because being able to imagine what the Hebrew original might have been gives you wiggle room.

Good points, Jeff. Analysts routinely use debatable points in order to make determinations about the Book of Mormon that they assert as conclusive. Good you're pointing out problems with this particular one-sided analysis, which is a frequent problem. Now that we have learned about the speculative nature of the DH, any argument RT might make is inconclusive. And no matter what RT might say about Smith and Arabian maps, to the reasonable person it must remain unlikely that Smith studied and mastered any such maps (because he would have had to go beyond consulting one). Of course, the hardened and biased among us will strain to make it likely.

I forgot to mention my main reaction to this post, which is sorrowful wonder. Mr Lindsay, sir: you put a lot of careful thought and intelligence into this stuff. I'm afraid I still believe that you, and a few other people like you, are putting more and better effort into justifying Joseph Smith's fraud than he ever put into making it in the first place. I hope and pray that all this effort can somehow not be wasted.

to the reasonable person it must remain unlikely that Smith studied and mastered any such maps (because he would have had to go beyond consulting one).

Not so. With the right map in front of you, it would take very little time and effort to get every single one of the travel directions relating to Nephi's Arabian journey, to wit:

(1) Travel south-southeast from Jerusalem for many, many days.

(2) Near a spot called Nahom, turn left and travel many, many days.

(3) End up somewhere on the seacoast.

To get the above, one need only spend a minute or so perusing an early map such as the 1771 Bonne Map of Arabia.

OK, so here the settlement near the eastward turn is "Negem" rather than "Nahom," but still: the "g" sound on this map might simply be a vocalized version of the "kh" phoneme (on other early maps, according to FAIR, it's rendered "Nehhm").

Maybe so. My immediate point is simply that there would be no need for Joseph to have "studied and mastered" an early map in order for it to serve as a source for the Nephite itinerary. If that itinerary was inspired by such a map, it would only take a few minutes to get the whole thing. Anon 1:36 is setting the bar way too high here.

Nice work Jeff. I too had noticed how much RT hung on the exilic dating of P, while ignoring the single most prominent modern scholar on the topic, but had other things on my plate. You might want to add as a resource Kevin Barney's excellent Dialogue essay, "Reflections on the Documentary Hypothesis." And of course, things like my essay in Glimpses of Lehi's Jerusalem on First Temple Theology, and Alyson Von Feldt's Occasional Paper essay on the Wisdom Traditions in the Book of Mormon. And John Welch's recent book on Legal Cases in the Book of Mormon. And perhaps Robert Smith's essay on the Book of Abraham as showing J source characteristics. Robert Alter on The Art of Biblical Literature for type scene and allusion.

And I really like the satellite view of the Arabian peninsula over Kent Brown's shoulder in the Journey of Faith video. Sand sand sand, and one tiny patch of green, due east of Nahom.

When the critics find something that "proves" the Book of Mormon is made up all the other critics and rabid anti Mormons jump with glee and accept the information without serious questions, and don't question anything.

BUT……when LDS just mention that something might show the Book of Mormon is a true ancient text the rabid antis foam at the mouth while throwing insults, make accusations, and blah blah blah……same old tiring, nit picking, twisting blather.

There is no proof Joseph Smith was committing a fraud, James Anglin. Prove it. You critics keep saying it but don't show proof.

Anon- 4;05-

I would not call James Anglin an anti-mormon. A hearty skeptic… yes. But that is totally understandable. From what I have seen, he has been skeptical, but very friendly and respectful to Mr. Lindsay and others. I mean he has made reasonable suggestions based on a naturalistic view. In my honest opinion, it just being chance between nhm and nahom is still the most logical naturalistic explanation.

Whether there are other evidences for Book of Mormon historicity or not, Nahom has been called the best archeological evidence to date by Jeff Lindsay himself. That's exceedingly strange, considering that less than 1% of Book of Mormon history takes place on the Arabian peninsula. A neutral observer would have to conclude that the writer(s) of the Book of Mormon knew more about names of tribes in Arabia than tribes in Mesoamerica, just as one would have to conclude that Book of Mormon peoples had more contact with Greek speakers than with Mayan speakers. If we stipulate that Nahom is evidence for BoM historicity, apologists for Mesoamerica have some explaining to do.

Thanks so much Jeff.

Jerome,

Mesoamerica doesn't have the historical continuity that we find in the middle east.

Jack

Archeological digs are not as prevalent in Central and South America as it is in the Middle East. The Middle East attracts more attention by scholars and archeologists, probably due to the fact that three major religions come from there.

The majority of Central and South America has not even been looked at by archeologists, much less dug up and researched. Many sites that have been found but not examined by digs and research have been destroyed.

The Middle East is dry and arid for the most part, perfect for preservation of artifacts. Central and South America are wet and humid which are not ideal conditions for artifact preservation.

It is unfortunate that the MesoAmerican setting for Book of Mormon events has taken hold, just as some believe in the Heartland theory. Both sides ignore much evidence that is found in the Book of Mormon. Both sides manipulate certain information to conform to their particular theories, beliefs and biases.

Hi Jeff,

I'm glad that you found my post interesting and provocative and worth engaging with. Just so there would be no misunderstanding, I thought I would briefly respond to several of your points:

"As I'll show below, one of the most important things he misses is the significant scholarship of Richard Elliot Friedman who persuasively demonstrates that the priestly text, P, which provides much of Pentateuch, was not a late manuscript from after the Exile, but much more likely comes from the time of King Hezekiah, dating it to before Nephi's time (see Friedman, Who Wrote the Bible, second edition, (New York: HarperCollins, 1997)). Thus it is no longer impossible for priestly material to have been known to Nephi."

I'm aware of and have read Friedman and that a few biblical scholars (influenced by Kaufmann) have been wont to date P to a period earlier than the exile. But there are enormous problems with this approach and in the last 20 years or so it has tended to be rejected by most mainstream scholars. In short, Friedman's treatment of this question is somewhat dated and has been superseded by more recent work. I myself have done quite bit of work on the question of dating biblical texts and I feel pretty confident that even an exilic dating of P is too early. If you would like a bibliography on this subject, I would be happy to oblige.

"but the Exodus story is an ancient one that was widely known among the Jews of Nephi's day."

I don't think you have reasonably substantiated this statement by any means. It was widely known among Judahites of the late 7th century-early 6th century and yet doesn't appear in authentically dated works from this period, such as in prophetic literature?

"As I'll also show that the references in the Book of Mormon to themes in the Pentateuch lack the major unique elements that characterize P (the importance of central sacrifices, an emphasis on Aaron, etc.), so the case for Nephi relying on material unique to P may be questioned."

Those are not the defining features of P by any means, so I'm a little confused about what you mean here. I have already shown that parts of the BoM narrative are unquestionably dependent on P, but not on a form of P separate from the combined P + non-P narrative.

"On the other hand, some LDS scholarship suggests that the brass plates may have been a largely Elohist (E) document, with strong influence from the Northern Kingdom, which is plausible given that the brass plates are a record associated with the tribe of Joseph."

This idea is problematic on a number of levels, since 1) it is not even clear that there was such a thing as an Elohist document; Pentateuchal scholars are increasingly skeptical of this notion, and I happen to agree with them; there is only P and early non-P and late non-P. 2) The BoM is dependent on more than just a putative E, it is dependent on P, early non-P, and late-non P, all in their combined form or the current form of the Bible. 3) None of this material demonstrates a clear connection to the northern kingdom, IMO.

"In fact, he's retelling and probably reshaping his story (not fabricating it!) to emphasize sacred themes in much the same way that the authors of the Bible, according to biblical scholars, may have adapted their writings to achieve specific purposes."

The heavy dependence on Exodus is a problem for traditional historicity for multiple reasons that I have already identified. I am very confident that you would not be able to find one example of an author in the Old Testament doing something comparable to what we find in 1 Nephi, that is, patterning one story almost completely off of another.