Fun with Dice in a Workshop for Management

“Facts”

and “data” are what most people use when they make decisions,

especially decisions that others see as hopelessly biased and idiotic.

The challenge is learning how to interpret facts and how to analyze data

so that are decisions are less likely to be blunders based on the many

biases and fallacies that can mislead all of us.

In a

training class on decision making that I was invited to do for managers

in one of my employer’s groups in China, I brought in a big bag of dice

to help local managers understand a serious example of self-deception in

leadership. In particular, I sought to illustrate why criticism of

employees for poor results seems to work better than praise for good

results. It’s an example where solid experience and significant data can

actually mislead and deceive..

Everybody in a group of

about 50 people were given three dice. I then explained their KPIs (Key

Performance Indicators–an important phrase in modern Bizspeak) for the

exercise: the company needs high scores. Everyone was asked to shake

their dice and roll them once, then record their score. The few with the

highest scores (e.g., a sum of 15 or higher) were brought up to the

front. A group with about the same number of people with the lowest

scores (e.g., less than 6) was also brought up to the front.

Now

it was time for their performance review. I approached the high

performers and personally congratulated them. I shook each person’s

hand, thanked them for their amazing achievement, gave them gifts (a

candy bar) and cash incentives (a Chinese bill–real money), and praised

them as good examples for the rest of the company. The whole room then

joined me in loud applause for these high-achievers.

Then

it was time for consequences for the low-performers. I shook my head,

grimaced, wagged my finger at them, and scolded them for their failure

in giving such disappointing results. They were a shame to the company,

and we might need to demote them or fire them if they didn’t shape up.

With

proper rewards and punishments having been meted out, the people in

these two outlier groups were given three more dice each and allowed to

roll again. Amazingly, the average score of the former top performers

now dropped significantly. Almost everyone in that team did more poorly

after receiving praise and rewards. But for the ones who had been

scolded and criticized, a notable improvement was observed. Almost all

of them showed significant gains in their scores. Wow, praise hurts and

criticism helps, right?

This pattern is fairly

reproducible, and coincides with the vast experience of many coaches,

bosses, generals, and leaders of all kinds: criticism and punishment

works better than praise; yelling works better than kindness. They have

solid experience to prove it, and they are often right, in a sense, but

also perhaps terribly wrong.

Obviously, the results

with the dice were not likely to be affected by praise or rewards (as

long as the participants behaved honestly). What was happening here is a

common statistical phenomenon that results in a great deal of

self-deception in many fields of life. The phenomenon is “regression to

the mean.” When there is a degree of randomness, as there is in much of

life, random trends that depart above or below the mean tend to come

back. Results that are extreme are often statistical outliers,

explainable by chance, that are not necessarily caused by the

explanations we try to concoct. It’s why athletes who make it to the

cover of famous sports magazines after a string of remarkable successes

tend to disappoint immediately after, leading to the “Sports Illustrated

jinx” which may not be a real jinx at all. It’s the reason why highly

intelligent women such as my wife tend to marry men who are less

intelligent, like certain bloggers around here. Since the correlation

between female and male intelligence in marriage is not perfect and

therefore involves some degree of randomness, the most intelligent

outliers among females will tend to marry men who are not such extreme

outliers themselves, and the probability is that they will tend to be

less intelligent. This works both ways.

Two Books That Inspired My Workshop

My

experiment with dice and other parts of my workshop were inspired in

part by two outstanding books that I recommend. The exercise with dice

was inspired by a story in Thinking Fast and Slow by Daniel

Kahneman (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011). I picked this up

for airplane reading a couple years ago and found a real gem that I have

applied in a variety of ways, though I still readily fall into many of

the fallacies of human thought that so easily beset us. The story that

motivated my dice exercise for management came from Chapter 17,

“Regression to the Mean,” pp. 175-176.

Kahneman, winner

of the Nobel Prize in economics, once taught Israeli air force

instructors about the psychology of effective training. He stressed an

important principle: that rewards for improved performance worked better

than punishment for mistakes. This is something that we employees tend

to understand easily, but is often a mystery to those dishing out the

punishments and rewards. One of the instructors challenged him and said

that this principle was refuted by his own extensive experience. When a

cadet performed exceptionally well and was praised, he would usually do

worse on the next exercise. But when someone performed poorly and was

criticized, he usually did better on the next run. This was a “a joyous

moment of insight” to Kahneman, who recognized an important application

of what he had been teaching for years about the regression to the mean.

The instructor had been looking for a cause-and-effect explanation to

natural, random fluctuations, and had developed an iron-clad theory that

was dead wrong. He had extensive real data, but had been deceived by a

failure to understand the impact of randomness. Real data + bad

statistics (or bad math) = bogus conclusions.

Regression

to the mean is one of several important principles Kahnema discusses.

Many have roots in mathematics. All have connections to human psychology

and the way our brains work. Kahneman is brilliant in illustrating how

often we make flawed decisions, and gives us some tools to overcome

these tendencies.

Related to Kahneman’s work is another

math-oriented book which I relied on in my workshop on decision making,

and which I highly recommend: Jordan Ellenberg, How Not to be Wrong: The Power of Mathematical Thinking (New York: Penguin Press, 2014).

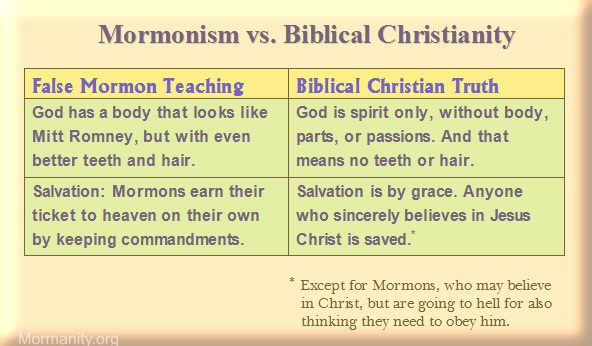

Ellenberg

shows how basic mathematics can quickly expose many of the fallacies

that we make in our thinking and decision making. Some of his

discussions have application to matters that come up in discussions of

LDS religion and in evaluation of evidence to support or discredit a

theory. He decimates one of the classic “Texas sharpshooter” disasters

in religious circles, the utterly bogus methodology used in The Bible Code

in which the Hebrew text of the Old Testament was treated as a

miraculous, absolutely perfect text filled with hidden prophecies that

could be obtained by mathematically rearranging the letters of the text

in numerous different grid patterns and then searching for new words in

something of a hidden-word puzzle. With computerized tools, thousands of

grids could be formed to lay out the letters in new two-dimensional

patterns and then these patterns were searched to find all sorts of

modern topics.

There’s an old joke about a man in Texas

who took a rifle and fired a few dozen random rounds into the side of a

barn. Wherever the shots were clustered together, he painted a target

around them and then told people that he was a sharpshooter. Drawing

circles around spaced-apart Hebrew letters on, say, arrangement number

47, 356 and finding a hidden prophecy is analogous to the Texas

sharpshooter.

Further, the very premise of a perfect

text for the study is completely without logic. There are multiple

versions of the ancient Torah with obvious gaps and uncertainties (e.g., compare the Torah in the Dead Sea Scrolls to the version used today: there are differences).

Changing one letter in the text would through off the alignments on the

selected grid patterns that give mystical results, making the whole

exercise obviously bogus.

In “Dead Fish Don’t Read

Minds” (Chapter 7), Ellenberg warns of the dangers of amplifying noise

into false positives when we have the resources of Big Data to play

with. With numerous variables to explore and map, it is incredibly easy

to find some that seem to correlate. This was brilliantly illustrated in

a real but still somewhat tongue-in-cheek paper that managed to be accepted for presentation at the 2009

Organization for Human Brain Mapping in San Francisco, where UC Santa

Barbara neuroscientist Craig Bennett presented a poster called “Neural correlates of interspecies perspective taking in the post-mortem Atlantic Salmon: An argument for multiple comparison corrections.” (See discussion at Scientific American.)

Basically, this paper reported statistical results from MRI brain

mapping taken in a dead fish as the fish was shown photos of people in

different emotional states. Dr. Bennett used the power of Big Data to

explore MRI signals from millions of positions and found a couple spots

in the fish’s neural architecture where the fluctuates corresponded well

with the emotional state shown in the photos. His paper was a clever

way of illustrating the dangers of using Big Data to find correlations

that really don’t mean anything, much like the work to find “smoking

guns” for Book of Mormon plagiarism by doing computer searches of short

phrases with hundreds of thousands of books to toy with.

Ellenberg

is often critical of religion and believers, and probably with good

reason, and mocks some aspects of the Bible a time or two, but religious

people can learn much from his mathematically sound approach to

thinking.

What Are the Odds of That? Actually, Unlikely Results are Guaranteed

The

many fallacies explored by Kahneman and Ellenberg can affect all of us

in our thinking and decision making. When it comes to apologetics,

Latter-day Saints can fall into related traps if we treat anything from

anywhere, anytime as potentially being a relevant parallel to the Book

of Mormon or other LDS works. Not every New World drawing of people in

two or more tones implies that we are looking at Nephites and Lamanites.

Not every drawing of a horse means we are looking at evidence for Book

of Mormon horses. And a place called Nehem on a map of Arabia is not

necessarily evidence that a name like Nahom existed anywhere in Arabia

in Lehi’s day. Those things can be random parallels. If they are

meaningful, there should be further data that can support the hypotheses

put forward. Such finds would be most meaningful if they are part of a

large body of information from multiple sources that can serve as

convergences useful in assessing the particular question at hand, such

as “Is the story of Lehi’s trail plausible? Could there have been a

place called Nahom where Ishmael was buried, with a fertile place like

Bountiful nearly due east?” Such questions can be framed in ways that do

not leave the infinite wiggle room of Bible Code explorations.

(It was such a question, in fact, that motivated Warren Aston to

undertake exploration in the Arabian Peninsula at great personal cost

with predetermined criteria for Bountiful, a target already drawn before

he ever touched the coast of Oman.)

When we are

exploring a hypothesis, false positives can easily result from errors in

thinking due to failure to understand randomness and regression to the

mean, as well as other mathematical and logical fallacies. A key element

in the field of statistics is recognizing that a random result can seem

to support a hypothesis when there is not actually a cause-and-effect

relationship. The science of statistics provides tools and tests to help

differentiate between what is random and what is real, though it

certainty is almost always elusive. Statistics gives us some tools to help reduce the risk of seeing things

that aren’t there, or to know when we might be missing something that

is (these topics involves the issues of “significance” and “power,” for example). Even for those trained in

statistics, there are abundant errors that can be made and false

conclusions made.

I’m not a statistician, but I did

have 10 hours of graduate level statistics and have frequently had to

rely on statistics to assess hypotheses. I even published a little paper

on a mathematical issue related to a statistical issue known as the

“collector’s problem.” The publication (peer-reviewed, but still lightweight, IMO) is J.D. Lindsay, “A New Solution for the

Probability of Completing Sets in Random Sampling: Definition of the

‘Two-Dimensional Factorial’,” The Mathematical

Scientist, 17: 101-110 (1992), which you can also read online

as a Web page or as a Word document. But what really

matters is that I am married to a statistician (M.Sc. degree in

statistics, now math teacher at an international school in

Shanghai)–what are the odds of that? Well, 100%, since that’s what

happened.

That reminds me of the many mistakes that

people on both sides of the debate can make as they argue probabilities.

It’s easy to see significance in something that happens by chance,

especially when we find something that did happen, possibly by chance,

and then try to make a case for how improbable that was. Richard Feynman

once joked to a class that one the way to campus that morning, he saw a

car with a specific license plate, ARW 357. “Of all the millions of license plates in the state, what was the chance that I would see that particular one tonight?” This fallacy of a posteriori

conclusions is an easy one to make. It’s inevitable that any particular

license plate will be rare, maybe even unique in all the world or at

least all the state. That odds of that happening are low–a priori,

before the event–but a posteriori, the odds are high, as in

100%. Making much of something because it is unusual is an error. But

again, today, much of the serious evidence being raised for Book of

Mormon plausibility is not of that nature.

Parallels occur

all over the place. Parallel words, themes, and motifs occur across

large bodies of literature, even when they are surely unrelated. I can

take any two texts and find some parallels. Within a sufficiently large

text, I can probably find parallel words and phrases that I can sketch

out as a chiasmus. If we scour all the names introduced in the Book of

Mormon, we should not be surprised to find a few might have apparent

connections to ancient languages. We might even not be shocked to find

an occasional one whose purported meaning might be construed to relate

well to its context. But when numerous names begin to have support and

offer useful new meaning for the text, when things like Hebraic

wordplays occur many times and in interesting, meaningful ways, then the

evidence can become more significant. When linguistic and

archaeological evidence bring about interesting and repeated

convergences, it may be time to take a deeper look at the evidence

rather than assuming it’s all chance.

Seemingly

unlikely findings are actually quite likely to happen. That truism,

however, is not an excuse to disregard meaningful bodies of evidence and

convergences that enlighten a text in question.

Progress in Avoiding False Positives

Fortunately,

the risk of methodological fallacies is frequently and openly

considered among many LDS apologists, contrary to the allegations of

critics who sometimes seem blind to their own biases and methodological

flaws.

For example, while chiasmus can and does occur

randomly, just as rhymes and other aspects of poetry can be found in

random text, there are reasonable criteria for evaluating the strength

of a chiasmus that can help screen random chaff from deliberately

crafted gems. The possibility of false positives was an important factor

in the analysis of John Welch as he explored the role of chiasmus in

scripture. Others build upon his foundation and even offered statistical

tools for evaluating chiasmus. It is still possible for something that

appears elegant, compact, and brilliantly crafted to be an unintended

creation, but we can speak of probability and plausibility in making

reasonable evaluations.

In the early days of LDS

apologetics, evidence of all kind was enthusiastically accepted. But

gradually, I see LDS writers becoming more nuanced and cautious. A prime

example of this is, in my opinion, Brant Gardner in his book, Traditions of the Fathers: The Book of Mormon as History

(Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2015). He is fully aware of the

risk of fallacious parallels, but in evaluating the relationship between

a text and history, they must be considered. What matters is how they

are considered and what they data can plausibly support. On page 47

[visible in an online preview],

Gardner discusses an insight from William Dever, a prominent professor

of Near Eastern archaeology and anthropology at the University of

Arizona who has been excavating in the Near East for several decades:

Some form of comparison between text and history is always required to discern

historicity.

Texts are always compared to archaeology and/or other texts. Sometimes

even artifacts require explanation by comparison or analogy to similar

artifacts from another culture. Comparisons must be made. The problem

cannot, therefore, reside in an absolute deficit in any methodology that

makes comparisons, but rather in the way the comparisons are made and

made to be significant. One important type of controlled parallel is

ethnographic analogy. Dever explains his version of this method:One

aspect shared by both biblical scholarship and archaeology is a

dependence on analogy as a fundamental method of argument. . . .The

challenge is to find appropriate analogues, those offering the most

promise yet capable of being tested in some way. Ethnoarchaeology is

useful in this regard, particularly in places where unsophisticated

modern cultures are still found superimposed, as it were, upon the

remains of the ancient world, as in parts of the Middle East. Analogies

drawn from life of modern Arab villages or Bedouin society can, with

proper controls, be used to illuminate both artifacts and texts, as many

studies have shown. [William G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? What Archaeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel (Grand rapids, Michigan: Eerdmans, 2001), pp. 77-78.]

Dever’s

work deals with the concept of “convergences” wherein multiple lines of

evidence, such as evidence from archaeology and from a text, come

together and support the historicity of a text in question. In spite of

the risk of fallacious parallels or false positives, convergences can be

strong and can create compelling cases for the historicity of a text.

Dever’s work is also relied on by John Sorenson in Mormon’s Codex,

where extensive correspondences between Mesoamerica and the Book of

Mormon in many different topical areas are explored. Gardner observes

his requirements for a convergence are more demanding than the criteria

in Sorenson’s approach. But I feel both authors are aware of the risk of

random parallels being mistaken as evidence, and are seeking to provide

a thorough methodology that combines multiple approaches to establish

meaningful though tentative connections that do more than just buttress

one point, but which also provide a framework that solves other problems

and makes more sense of the text. Convergences that are fruitful and

lead to new meaningful discoveries are the most interesting and

compelling, though there is always the risk of being wrong.

Gardner’s

approach also draws upon wisdom from the field of linguistics, which

offers many analogies to the problems of evaluating the historicity of a

text based on parallels and convergences.

As a result

of my orientation, I suggest that we will be best served by an approach

applied with great success in the field of historical linguistics. Bruce

L. Pearson describes both the problem and the solution:Sets

of words exhibiting similarities in both form and meaning may be

presumed to be cognates, given that the languages involved are assumed

to be related. This of course is quite circular. We need a list of

cognates to show that languages are related, but we first need to know

that the languages are related before we may safely look for cognates.

In actual practice, therefore, the hypothesis builds slowly, and there

may be a number of false starts along the way. But gradually certain

correspondence patterns begin to emerge. These patterns point to

unsuspected cognates that reveal additional correspondences until

eventually a tightly woven web of interlocking evidence is developed.

[Bruce L. Pearson, Introduction to Linguistic Concepts, 51]Pearson’s

linguistic methodology describes quite nicely the problem we have in

attempting to place the Book of Mormon in history. We cannot adequately

compare the text to history unless we know that it is history. We cannot

know that it is history unless we compare the text to history. We

cannot avoid the necessity of examining parallels between the text and

history.The problem with the fallacy of parallels is

that it doesn’t protect against false positives. What is required is a

methodology that is more recursive than simple parallels. We need a

methodology that generates the “tightly woven web of interlocking

evidence” that Pearson indicates resolves the similar issue for

historical linguists.

In my studies of foreign

language, I’ve often been intrigued by false cognates that can trick

people into imagining connections between languages that might not

exist. An interesting involves the English and Chinese words “swallow.”

In English “swallow” can be a noun involving the ingestion of food or

liquid and it can be a noun describing a particular bird. Something

similar happens in Chinese, where 燕 (yan, pronounced with a

falling tone) is the Chinese character for swallow, the bird, while the

same sound and nearly the same traditional character, 嚥, is the verb, to

swallow. The latter just adds a square at the left, representing a

mouth. It’s a cool parallel. If this kind of thing happened frequently,

or if there were, say, hundreds of ancient Chinese words that showed

connections to English, we might have a case for a systematic

relationship between the languages. But there really are not meaningful

connections between the languages apart from modern borrowed words and a

few rare occurrences that can be chalked up to chance. But exploring

parallels between languages is a vital area for research and study–it’s

how relationships between languages are established in the first place

and can help fill in huge gaps in the historical and archaeological

record. When the parallels become numerous and show patterns that begin

to make sense, it’s possible that two languages share historical

connections. To me, Gardner’s appeal to lessons from historical

linguistics makes sense. Parallels can be real and meaningful, or they

can be spurious. It’s a matter of exploring the data and being open to

convergences that enlighten and reveal useful new ways of understanding

the data.

In evaluating the Book of Mormon, I believe

LDS scholars today generally recognize that there is a risk of finding

impressive parallels to, say, ancient Mesoamerica or ancient Old World

writings that may be merely due to chance.

In my own

writings, I’ve often pointed to the risk that my conclusions are based

on chance, misunderstanding, and so forth, and use my blog as a tool to

get frequent input from critics. In spite of their repetitive dismissal

of all evidence as mere blindness, bias, and methodological fallacy on

our part, occasionally they engage with the data and provide some

helpful balance or even strong reasons to reject a hypothesis. It’s a

healthy debate. We don’t have all the answers, we are subject to biases

of many kinds, but there is still a great deal of exploration and

discovery to do that goes beyond finding random items and painting a

bullseye around it.

Sometimes the target was there

before the bullseye was there long before the bullet holes were

discovered, as in the Arabian Peninsula, which has long been a target

for criticism of the Book of Mormon before the field work was done that

helped us recognize just how many impressive hits had been scored by the

text in First Nephi.

Methodological Error: Not Unique to Mormons

Fallacies of logic and math, of course, aren’t unique to believers.

When

it comes to the Texas sharpshooter fallacy and related problems with

false positives, the critics of Mormonism also have some particular

gifts in this area as they scour modern sources to support theories of

plagiarism or modern fabrication of the Book of Mormon. Examples of

improperly finding meaning from randomness coupled with serious

methodological flaws include computer-assisted database searching among

thousands of texts for short phrases found in common with the Book of

Mormon or allegedly pointing to implausible sources for the Book of

Mormon such as the The Late War Between the United States and Great Britain.

Naturally, texts written in imitation of the King James style score

highly with their abundance of such words as “thou” and “thee” instead

of “you,” but there is no substance to the claim of plagiarism.

“Parallelomania,”

in fact, is an increasing problem in the works of critics purporting to

explain the Book of Mormon by appeals to numerous other texts. An

excellent discussion of false positives from parallels in an anti-Mormon

work is found in “Finding Parallels: Some Cautions and Criticisms, Part One” by Benjamin L. McGuire in Interpreter: A Journal of Mormon Scripture 5 (2013): 1-59. In Part Two, he gets more heavily into the methodology of treating parallels.

There

is no doubt that there are many parallels, as there can be between any

two unrelated texts. One of my early essays on the Book of Mormon sought

to expose the problem of false positives for those claiming Book of

Mormon plagiarism by coming up with even stronger examples of parallels

than the critics were delivering. The result was my satirical essay, “Was the Book of Mormon Plagiarized from Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass?” (May 20, 2002, but slightly updated several times since then), which Brant Gardner kindly quotes from in The Book of Mormon as History

(2015, pp. 44-45). Based on the data alone, one can make a strong case

that the Book of Mormon borrowed heavily from Whitman’s 1855 work or at

least had a common source (perhaps Solomon Spaulding was plagiarized by

Whitman as well?). That’s ridiculous, of course–but the parallels show

just how easy one can be mislead by random parallels, coupled with a

little creativity and a dash of zeal. If those claiming plagiarism can’t

clearly outdo Whitman as a control, a reasonable case has not been

made.

One of latest posts at Mormanity dealt with my

explorations of a hypothesis from Noel Reynolds about the possibility of

the Book of Moses and the brass plates sharing some common material.

Reynolds’ article includes a detailed discussion of what it takes to

determine the relationship between two texts. It begins with a

consideration of the requirements for one text to depend on another. He

is aware of the risk of random parallels and discusses the issues rather carefully, aware of risks and aware of the kind of evidence that is required to find meaningful parallels. He also offers a test case also in

the Book of Abraham. Does it depend on the Book of Mormon or visa versa?

Very little sign of relationship is evidence in that case. But further tests and more rigor is needed. It’s very tentative and speculative, but interesting. Not completely illogical methodology at all, though the results are controversial.

But just as

alleged evidence sometimes falls prey to the sharpshooter fallacy as it

is improperly used to buttress a theory, the sharpshooter fallacy can

easily be misapplied to dismiss legitimate, meaningful evidence. A

noteworthy example is found when Dr. Philip Jenkins, a professor of

history, dismisses the significance of the evidence for Nahom in the

Arabian Penninsula, an important but small piece of the body of evidence

related to the plausibility of Nephi’s account of his journey through

Arabia along the route we often call Lehi’s Trail. Jenkins has this to say as he dismisses this evidence:

One other critical

point seems never to have been addressed, and the omission is amazing,

and irresponsible. Apologists argue that it is remarkable that they have

found a NHM inscription – in exactly the (inconceivably vast) area suggested by the Book of Mormon. What are the odds!By the way, the Arabian Peninsular covers well over a million square miles.

Yes

indeed, what are the odds? Actually, that last question can and must be

answered before any significance can be accorded to this find. When you

look at all the possible permutations of NHM – as the name of a person,

place, city or tribe – how common was that element in inscriptions and

texts in the Middle East in the long span of ancient history? As we have

seen, apologists are using rock bottom evidentiary standards to claim

significance – hey, it’s the name of a tribe rather than a place, so

what?How unusual or commonplace was NHM as a name element in

inscriptions? In modern terms, was it equivalent to “Steve” or to

“Benedict Cumberbatch”?So were there five such NHM inscriptions

in the region in this period? A thousand? Ten thousand? And that

question is answerable, because we have so many databases of

inscriptions and local texts, which are open to scholars. We would need

figures that are precise, and not impressionistic. You might conceivably

find, in fact, that between 1000 BC and 500 AD, NHM inscriptions occur

every five miles in the Arabian peninsular, not to mention being

scattered over Iraq and Syria, so that finding one in this particular

place is random chance. Or else, the one that has attracted so much

attention really is the only one in the whole region. I have no idea.

But until someone actually goes out and does some quantitative analysis

on this, you can say precisely nothing about how probable or not such a

supposed correlation is.

It’s a fair question, but one

that has been answered for many years. The NHM name turns out to be

exceedingly rare in the Arabian Peninsula. As far as we can tell, it is

only found in the general region associated with the ancient Nihm tribe.

It’s in the region required by the Book of Mormon, with a convergence

of data showing that this tribal name was there in Lehi’s day, in a

region associated with ancient burial sites, a region where one can go

nearly due east and reach a remarkable candidate for Nephi’s Bountiful.

It’s part of an impressive set of convergences pointing to plausibility

for the journey of Lehi’s trail. In light of the new body of evidence,

the task of critics has suddenly shifted from mocking the implausibility

of Nephi’s account to explaining how obvious it all is in light of the

knowledge that Joseph and his technical advisory team surely must have

found by searching various books and maps, all the time lacking any

evidence that such materials were anywhere near, and still being unable

to explain the motivation for plucking “Nehhm” or “Nehem” off a rare

European map amidst the hundreds of other names, ignoring every

opportunity to use the map for something useful. They also fail to

explain how any of these sources could have guided Joseph to fabricate

the River of Laman and Valley of Lemuel, the place Shazer, or the place

Bountiful, each with excellent and plausible candidates. Here appeals to

the Texas sharpshooter fallacy or any other fallacy miss the reality of

serious evidence and serious convergences that demand more than casual

dismissal and scenarios devoid of explanatory power.

Yes, it’s fair and important to worry about false positive (and false negatives) as we approach issues of evidence for the Book of Mormon, and against the Book of Mormon as well. Methodology, logic, and intellectual soundness are fair topics for debate. Let’s keep that in mind as we explore the issues and watch out for the many fallacies that can catch us on either side of the debate.

Sorry Jeff. You didn't get this peer reviewed. It is not admissable if you don't get it peer reviewed.

(I bit my tongue.)

Glenn

Jeff, I'm puzzled that you would write that chiasmus can and does occur randomly, etc.

Has anyone argued that the obvious chiasmuses in the Book of Mormon "occur randomly"? My argument has always been that they're in the Book of Mormon because they're in the Bible, and the author of the BoM was imitating the Bible. This has nothing whatsoever to do with randomness.

Glenn, I wish you could understand that secular academic peer review is not the enemy of LDS apologetics. It is, however, the enemy of bad apologetics, which is all the more reason apologists should pursue it.

Orbiting,

Do you have evidence for your assertion that chiasmus only appear in the BoM because the structures were copied from the Bible? Did this occur randomly? It seems to be that you are implying that Joseph Smith just read the Bible, and naturally produced chiasmus without thinking about it. Or if it was done intentionally then why was it never mentioned by Joseph Smith? I find it hard to believe that he intentionally put them in there and then forgot that he had done it.

If it was something that "anyone familiar with the KJV in the 19th century could have done" then books like The Late War, which was written specifically to mimic the Bible, would have chiastic structures, much like those found in Deuteronomy 8 and Numbers 8. If "anyone" could have done it then we should find many examples of chiasmus in literature from the 1800's. And if it was so prevalent that random farmers could produce it then why did it slip past every academic who studied language and literature up until about the 1920's? So where is your evidence? You say "apologists are not operating in good faith" yet you produce no evidence to support your rather astounding assertions.

Terrific post, Jeff.

Jack

Quantum, I'm saying that Joseph was very familiar with the sound of the KJV, and in writing the BoM he was trying to imitate that sound, and chiasmus is part of that sound, just like anaphora ("and it came to pass") is part of that sound, just like the cognate accusative ("he dreamed a dream") is part of that sound, and so on and on. In the course of trying to imitate the KJV's sound he naturally produced chiasmus (and many other biblical stylistic elements) without thinking about it.

But no, I'm not saying he put chiasmus in the BoM deliberately. What he did deliberately was try to imitate the biblical style. Think of it this way. Your comment contains adverbs. Did you put those adverbs in your comment deliberately? No, what you were doing deliberately was trying to craft a response to my claims. That's what you were deliberately and consciously thinking about. The adverbs got in there unconsciously. And you could have used those adverbs even if you had never in your life heard the term adverb. You're confusing the use of language with the conscious use of language, and further confusing the use of rhetorical techniques with knowledge of the academic terms for those techniques.

None of what I'm saying here is the least bit astounding. It's all rooted in our uncontroversial understanding of the way people acquire and use language.

Consider this passage from the famous "Ain't I a Woman" speech of former-slave-turned-abolitionist Sojourner Truth:

I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain't I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man – when I could get it – and bear de lash as well! And ain't I a woman? I have borne thirteen chilern, and seen 'em mos' all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother's grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain't I a woman?

The repetition of the same word or phrase at the end of successive sentences is known as epistrophe. I seriously doubt that Sojourner Truth ever heard this term or studied classical rhetoric at all. Must we therefore conclude that she couldn't have used epistrophe in her speech? Of course not.

Similarly, Smith's ignorance of the term chiasmus does not at all mean he couldn't have used chiasmus — no more than a child has to know the terms noun, verb, and direct object in order to use them in saying "I want a cookie." This sort of thing just comes naturally.

Before I respond more specifically to your demand for evidence, let me ask you this:

Do you believe Joseph knew how to read? If so, what is your evidence?

After I have your answers, I'll be happy to go on.

About chiasmus in the Book of Mormon: at least some of the Book of Mormon chiasmus is something that would be trickier to copy from the Bible, because it is really long and elaborate. To the extent that I want to ask: does any known ancient Hebrew writing really use such elaborate chiasmus? Or is this a hypertrophied form that is unique to the Book of Mormon — in which case it might be interesting, but it wouldn't count so much as evidence of authenticity as an ancient Hebrew text.

The other problem with such a gigantic Book of Mormon chiasm as the one in Alma is that it takes a bit of squinting to see the pattern. The chiasmic form only emerges, in the long text, if you assign the right subheadings to big chunks of verses. This supplies a considerable amount of wiggle room, and every element in the pattern can wiggle independently. If you don't take that wiggle room into account when you estimate the probability of the big chiasmic pattern occurring by chance, then simply because the pattern is long, you easily end up with an overwhelming likelihood that the pattern is real and deliberate. But if you think about how subjectively the verses were grouped and characterized, in order to define the pattern, you should really up the chance of randomness at each step quite a lot. The final probability that the long pattern is real then becomes awfully fuzzy, because small changes in the probability for each item make a big difference when they're multiplied thirty times. At the very least, though, one should say that the very existence of this big chiasm is a lot less clear cut than some apologists have made it out to be.

Not sure I could chalk Alma 36 up to an accident of cultural influence.

Jack

About this latest post: I'm quite impressed. Jeff seems to have quite a good grasp of the subtleties of inductive argument; I reckon he knows enough to appreciate pitfalls in arguments as well as anyone. Professional expertise might help one to recognize pitfalls more quickly, but if you take a bit of time to think about the reasoning, then I'm pretty sure that Jeff's level of statistical awareness is quite sufficient to do the job. Expertise in statistics isn't as big a deal as some people think.

People who don't do much math often seem to regard statistics as a black art. They know that if you don't follow certain arcane rules, your results will be invalid; but they have no idea why. On the other hand, they imagine that if you do follow the arcane rules, then your results will be guaranteed to be true, by the mystic power of statistics. They don't get the fact that statistics is just ordinary common sense, applied carefully. There are no rules so mystical that you can turn weak evidence into fact just by following the rules.

So on the one hand I'm reassured that Jeff, at least, is quite able to handle methodological discussions about inference from evidence. But on the other hand I still have the concern that at least some apologists may not appreciate just how much of that kind of discussion needs to be done.

A good example of what I mean is In my most recent comment before this one: the trickiness of quantitatively analyzing chiasmus. I've seen several Mormon apologists cite the high final probability estimate for deliberate chiasmus in Alma 36 that was claimed by one particular paper, as if citing that one paper was decisive. That's like counting somebody as Heavyweight Champion just because they showed up at the ring wearing shorts. Presenting a quantitative analysis is something, all right: it's like stepping into the ring. But that's just the beginning. You've got to go the distance. That can be tough.

I'm sure that critics and skeptics of Mormonism are also often guilty of underestimating the work involved in really establishing even basic points. The fact is that, even though a bunch of amateurs on either side may have enough wit and knowledge to thresh this stuff out properly, we may well not have the time to slog through to the end.

If that's true, then I think we should admit that, on either side, rather than kid ourselves about how strong a case we can make — for our against — in our spare time.

@ Jack:

"Not sure I could chalk Alma 36 up to an accident of cultural influence."

That's what I said. If it's there, it's too big to be an accident. The thing is: it's really not so clear that it's there. It's a loose and subjectively identified pattern in a long text.

One more point on the theme of how much attention the premises of inference really require.

"You have to go the distance" doesn't necessarily mean that everyone has to "engage the material". If a hundred dense pages are all based on one flimsy premise that isn't properly established, then carefully reading all those pages would be a poor use of an amateur's limited time.

In fact that's why things that might seem like mere preliminary details need so much careful attention. If you skimp on them, then no amount of detail built on top of them can make up for their flimsiness; if an opponent points out that flimsiness, you can't complain that they ignored all your other hard work. A skyscraper built on sand falls just as fast as a house.

Like James, I'm also impressed with this post. Jeff is taking some big steps down the road that leads eventually to a better understanding of the Mormon scriptures.

Maybe someday we'll see a similar post about the value of academic peer review. As I mentioned above, peer review is not the enemy of LDS apologetics — only of bad LDS apologetics.

As for Alma 36, there's another question that never seems to get discussed: What in the world would be the purpose of a 39-level chiasmus in the first place?

Techniques like chiasmus are used because they have certain effects on the reader/listener, such as making things more memorable. (Ditto, of course, for anaphora, alliteration, rhyme, rhythm, etc.) Which of the following is more memorable? This…

We should all support one another, both individually and as a group.

… or this:

All for one and one for all!

Clearly the latter is the one more likely to stick in the mind, and that's mostly because of its chiastic structure. Its chiastic structure has a clear and beneficial effect on the reader/listener. But I don't see how there could possibly be any such effect in the case of Alma 36. Even if it is a genuine chiasm — and not just a methodological artifact created via the clever use of ellipses — it's simply too big and loose and baggy to have any rhetorical effect. By the time you get to the end you've long since lost touch with the beginning. What, then, could possibly have been the point of creating it? This question applies whether its author was ancient or modern.

The idea that Alma 36 contains a massive chiasmus that is an artistic writerly creation (as opposed to methodological artifact) makes about as much sense as the idea that the BoM is rife with actual EModE (as opposed to scattered bulletholes made by a Texas sharpshooter). These things serve nicely as a hammer for the apologist, because they support the argument that Joseph could not be the author. But we should remember that, in addition to serving the modern purposes of the apologist, such literary marvels must have served some ancient purpose of the author.

At this point I guess the (bad) apologist might say this: The ancient writer's purpose was not to have a rhetorical effect on his ancient audience, but to conceal items in the text that, upon discovery some 1,500 or more years in the future, would confirm the faith of his modern audience. This is the point where the apologist starts preaching solely to the choir. This is the point where the apologist requires us to believe that, while Jeremiah was writing for an audience of 6th-century BCE Jews, Paul for an audience of 1st-century Christians, etc., Nephi and Mormon were writing specifically for an audience of modern Americans. We are being asked to believe something of this particular ancient text that is not true of any other ancient text that we know.

Well, um, okay…. But if we grant all this, we might wonder why these ancient authors would not attempt to persuade their future audiences by providing less equivocal evidence. But at this point the (bad) apologist starts talking about how, yes, God wants us to believe, but doesn't want to make it too easy for us to believe, etc. — and at this point Gentiles like me simply throw up our hands and say, "There's just no reasoning with you guys. You move the goalposts, your claims are never falsifiable, and whatever it is that you're doing here, you're not arguing in good faith. You're more interested in shoring up your testimonies than in searching for truth."

P.S. FWIW, a 21-level (but very loose and baggy) "chiasm" has been discovered/invented in The Late War — see here.

Please, let's stop with the lame critical analysis by the critics, and stop harping on Alma 36. A good critical analysis must consider at least Mosiah 3:18-19, Mosiah 5:10-12, Alma 41:13-14, and Helaman 6:9-11. See various Welch publications for more, and Edwards and Edwards (2004) BYU Studies for stats.

Also, orbitational analogizes from simple epistrophe to multi-level chiastic construction. Who thinks he's a reasonable analyst who's trying to check his biases in this case?

Anon 12:05, I didn't analogize simple epistrophe to multi-level chiasmus. I used epistrophe to challenge a particular apologetic assumption: that one must know the technical term for a rhetorical figure in order to use that rhetorical figure.

My argument about Alma 36 is that it's not a chiasmus at all — it's a methodological artifact created by the bogus method of (1) fishing in an expansive sea of text until finding a passage that (2) can be made to appear chiastic by strategically omitting non-chiastic portions of the text. Basically, Welch put his thumb on the scale. Any subsequent statistical analysis that fails to take this into account is meaningless.

(1) above is basically Texas sharpshooter. (2) is just intellectually dishonest. It's basically saying, "This passage is chiastic…" without adding "…except where it's not." It's like James's used-car salesman saying "With its new tires, new brakes, and new paint job, this car is in great shape…" without adding "…except for the leaky head gasket and worn-out transmission."

At any real academic journal this kind of stuff would be pointed out in peer review. That's why these arguments wind up only in pseudo-journals, like BYU Studies, where once again the thumb is on the scale.

If the aim is to do things like better understand the Mormon scriptures and persuade the outside world of their value, then secular academic peer review is your friend, not your enemy.

Peer review is the enemy only if the aim is to shore up the believer's testimony at all cost.

Please stop with Alma 36. Okay, not analogizing in one sense, but you're equating epistrophe to production of 7-level chiasmus. They're wholly different. The normal human mind cannot produce the latter subconsciously.

Okay, I'll stop with Alma 36. Will the apologists?

The normal human mind cannot produce the latter [7-level chiasmus] subconsciously.

Actually, I'm not so sure of that. There are plenty of examples of people spontaneously dictating some pretty complex stuff. In any case, Joseph Smith surely had an exceptional mind.

If you'd like to show us the 7-level chiasmus you're referring to, feel free.

If you google "Alma 36 chiasmus", the current sixth hit is the article in Dialogue by a guy named Wunderli, which points out a level of shakiness — in the very existence of this giant chiasm — that is disturbing to me. I'm not saying Wunderli has won the whole fight, but he certainly comes out swinging pretty hard for a few rounds. Maybe the chiasmus can somehow be salvaged, but after reading Wunderli's critque, I felt a bit annoyed that Mormon apologists hadn't been more up-front about how much scaffolding is needed to support this purported multi-level pattern.

From the way I'd read apologists referring to Alma 36, I was expecting something almost like a sonnet, with the chiasmus building line after line. Instead it's really an overlay that you have to put onto the text, by declaring passages of varying length to be 'about' certain topics. Perhaps it's not sheer invention — though at the moment that's what I think it is — but it's definitely not the striking literary landmark that I felt led to expect.

From Boyd F. Edwards and W. Farrell Edwards (2004).

See their article for formatting.

Mosiah 5:10-12 is a 6- or 7-element chiasm:

(a) whosoever shall not take upon them him the name of Christ

(b) must be called by some other name;

(c) therefore, he findeth himself on the left hand of God.

(d) And I would that ye should remember also, that this is the name

(e) that I said I should give unto you

(f) that never should be blotted out,

(g) except it be through transgression;

(g´) therefore, take heed that ye do not transgress,

(f´) that the name be not blotted out of your hearts.

(e´) I say unto you,

(d´) I would that ye should remember to retain the name written always

in your hearts,

(c´) that ye are not found on the left hand of God,

(b´) but that ye hear and know the voice by which ye shall be called,

(a´) and also, the name by which he shall call you.

Helaman 6:9-11 is a 6- or 7-element chiasm:

(a) And it came to pass that they became exceeding rich, [not exceedingly]

both the Lamanites and the Nephites;

(b) and they did have an exceeding plenty

of gold, and of silver, and of all manner of precious metals,

both in the land south and in the land north.

(c) Now the land south

(d) was called Lehi,

(e) and the land north

(f) was called Muloch,

(g) which was after the son of Zedekiah; (theophoric suffix)

(g´) for the Lord

(f´) did bring Muloch

(e´) into the land north,

(d´) and Lehi

(c´) into the land south.

(b´) And behold, there was all manner

of gold in both these lands, and of silver,

and of precious ore of every kind;

and there was also curious workmen, [i.e. skilled]

which did work all kinds of ore and did refine it;

(a´) and thus they did become rich.

Orbiting and James,

You guys know the Bible at least ten times better than Joseph did when he translated the Book of Mormon. So, now, your job is to sit down and in one long stream of consciousness write as beautiful and complex a chiasmus as is found in Alma 36. Don't think about it. Just let it flow. Let the influence the Bible has had on your prose dictate the outcome.

As for the purpose of Alma 36's structure: Come now. The center piece is about deliverence through Christ's atonement. Could there be anything more important to Nephite Christians?

Jack

For cryin' out loud, Jack — very, very few people have a genius for oral composition, and the vast majority of us don't. (I certainly don't.) This is why the "Book of Mormon challenge" is so meaningless. No serious student of the Book of Mormon has ever said that just anyone could have written the Book of Mormon.

Here's the challenge from Nibley:

Since Joseph Smith was younger than most of you and not nearly so experienced or well-educated as any of you at the time he copyrighted the Book of Mormon, it should not be too much to ask you to hand in by the end of the semester (which will give you more time than he had) a paper of, say, five to six hundred pages in length. Call it a sacred book if you will, and give it the form of a history….

Of course, what a more intellectually honest man would have said would be something more like this:

Since Joseph Smith was younger than most of you and not nearly so experienced or well-educated as any of you at the time he copyrighted the Book of Mormon, it should not be too much to ask any of you who have an exceptional genius for oral storytelling to hand in by the end of the semester a paper of, say, five to six hundred pages in length. Feel free to plagiarize a hundred or so of those pages straight out of the KJV. Don't worry about depth or complexity of character — cardboard cutouts will do. If you find your imagination running dry, feel free to steal as many plots and motifs as you like from the Bible. If it helps to steal the Noah's Ark plot, go right ahead and steal it, not just once, but twice….

This version is more honest, but lacks punch.

Jeff, Jack's comment is a good example of how a certain kind of LDS apologetics that works well with undiscerning believers can make the Church look stupid to outsiders. It looks good within the fold but ridiculous without. You really ought to stop peddling it.

One of the more unfortunate aspects of all this is the way the apologetics community is opting itself out of the emerging field of Mormon studies. As Mormon studies grows into a legit academic field, people like Dan Peterson, Bill Hamblin, and the rest will either have to abandon their apologetic hobby horses or wind up like the Young Earth Creationists, with no credibility at all outside their little coterie of fellow apologists.

P.S. — Anon 1:18, will you ask Jack to "please stop with Alma 36"?

I'll try to get to your two examples of chiasmus tonight or tomorrow.

Yes, Jack et al., please stop with Alma 36.

The Edwardses rigorously analyzed chiastic material in the BofM. Accordingly to their methodology, p = 0.02 that 4 compact chiastic passages occurred by chance. That's Orbiting Kolob's position (leaving Alma 36 aside, and replacing one of those with Alma 41:13-14 and another passage with clear chiastic organization). OK believes p < 0.5, p < 0.1, p << 0.1 many times over, for many different BofM elements. Thus the p that OK accepts for JSJr being the author is vanishingly small, yet he will stubbornly adhere to it, as many will.

Orbiting, while chiasmus can play a valuable role in organizing information for oral recitation, it also works well to add meaning and structure in written text. In Alma 36, Alma tells a story that he's already told twice before. First time was exulting over what had just happened–a very spontaneous, dramatic outpouring that doesn't show careful chiasmus. Same with his second retelling. But in Alma 36, years after his experience, he's had time to carefully compose it in a lengthy, formal passage as he gives instructions and teachings to his sons. This is his written record and for the most dramatic and important experience of his life, he has organized it carefully in chiasmus.

Part of the purpose of chiasmus is to give emphasis to key portions of the poetry. The pivot point is obviously the crux and typically is at the heart of the meaning. The outer portions (the beginning and the ending) are emphasized. When there is history being related, the middle portions can be loose and baggy. So whether Alma 36 is 21 steps of just 8 or 9 is not the important thing. Let's look. Here's the chiastic structure showing key words and verses, where you can see where things are compact and where they are loose:

(a) My son, give ear to my WORDS (1)

(b) KEEP THE COMMANDMENTS of God and ye shall PROSPER IN THE LAND (2)

(c) DO AS I HAVE DONE (2)

(d) in REMEMBERING THE CAPTIVITY of our fathers (2);

(e) for they were in BONDAGE (2)

(f) he surely did DELIVER them (2)

(g) TRUST in God (3)

(h) supported in their TRIALS, and TROUBLES, and AFFLICTIONS (3)

(i) shall be lifted up at the LAST DAY (3)

(j) I KNOW this not of myself but of GOD (4)

(k) BORN OF GOD (5)

(l) I sought to destroy the church of God (6-9)

(m) MY LIMBS were paralyzed (10)

(n) Fear of being in the PRESENCE OF GOD (14-15)

(o) PAINS of a damned soul (16)

(p) HARROWED UP BY THE MEMORY OF SINS (17)

(q) I remembered JESUS CHRIST, SON OF GOD (17)

(q') I cried, JESUS, SON OF GOD (18)

(p') HARROWED UP BY THE MEMORY OF SINS no more (19)

(o') Joy as exceeding as was the PAIN (20)

(n') Long to be in the PRESENCE OF GOD (22)

(m') My LIMBS received their strength again (23)

(l') I labored to bring souls to repentance (24)

(k') BORN OF GOD (26)

(j') Therefore MY KNOWLEDGE IS OF GOD (26)

(h') Supported under TRIALS, TROUBLES, and AFFLICTIONS (27)

(g') TRUST in him (27)

(f') He will deliver me (27)

(i') and RAISE ME UP AT THE LAST DAY (28)

(e') As God brought our fathers out of BONDAGE and captivity (28-29)

(d') Retain in REMEMBRANCE THEIR CAPTIVITY (28-29)

(c') KNOW AS I DO KNOW (30)

(b') KEEP THE COMMANDMENTS and ye shall PROSPER IN THE LAND (30)

(a') This is according to his WORD (30).

(cont. in next comment)

Get out Alma 36 and look at the opening lines and then the closing. These are compact and tight, clearly signaling an introduction and ending of a formal passage. Stuff in the middle is more disperse, and then we have the obvious focal point and pivotal point: he fears the presence of God, suffering the pains of a damned soul, harrowed up by the memory of his sin, and then everything changes, reverses at the pivot point. He remembers what he was taught about Jesus Christ, Son of God, and as he calls out to Jesus Christ, Son of God, his suffering is replaced with joy. He's no longer harrowed up, his pain is replaced with joy, and he longs to be in the presence of God. That's an amazing core of the chiasmus, giving emphasis that aligns with the emphasis of the Book of Mormon. It relates well to the theme of captivity and deliverance at the outer portions of the chiasmus. There's still enough structure in between, in the less important zones, to show chiasmic structure, but yes, there it is loose, as it often must be when relating events.

Alma 36 nicely illustrates the way chiasmus can help convey and amplify meaning. It's great poetry, cool literature, worthy of respect and not mere dismissal.

Anonymous,

That methodology is like looking at tree trunk in order to discover the fibonacci sequence in a tree. You have to back up a bit to capture it. And once you do you discover that the sequence is beautiful and real.

James,

Darned if we do and darned if we don't. At first it was believed that only a moron could have written the BoM — even Mark Twain believed that. Nowadays the consensus is that he must have been a genius. Which one is it?

Jack

In fact, I'd say that that methodology is a good example of what Jeff's talking about on this thread: False positives.

Now sit down and create your own chiasmus of similar length. Take all the time you need. Let it breath a little so it isn't stifled be structure and recount a beautiful life changing event.

Jack

Of note in the Helaman 6 chiastic passage is the following:

The phrase "an exceeding plenty" is currently found in Google books in a 1645 book and in a 1713 book (2nd ed.):

1645 EEBO A48432 John Lightfoot [1602–1675] A commentary upon the Acts of the Apostles

did bring in provisions in an exceeding plenty to the Jewes at Jerusalem for their sustenance in the famine,

"Exceeding rich" demonstrates a type for which the earliest text is completely consistent, against naturalistic expectation: "exceeding(ly)" modifying adjectives never takes the long form. By 1829, "exceedingly" + ADJ predominated and the trend favored it; yet in the dictation, perhaps more than 100 times, we always find "exceeding" + ADJ. These were all edited to the modern {-ly} form in 1920 and 1981. Even the KJB has "exceedingly mad" once.

The heavy "did" use with infinitives in this passage is found only in writings of the 16th and 17th centuries.

"There was" with plural complements was much more common in eModE than in modE. Because the dictation has many more indicia of being a literate, formal text than an illiterate, informal text, it is a better fit with eModE in this regard.

Curious has the older meaning of 'skillful':

1687 EEBO A31771 Charles I, King of England [1600–1649] Basiliká the works of King Charles the martyr

for He brought some of the most curious Workmen from Forein Parts to make them here in England.

The suffix -yahu matches Yahweh in the center of the chiasm.

Two of the above are strong indicators of eModE, and the match of a Hebrew suffix with the tetragrammaton is compelling, occurring at the center of a Hebrew poetic structure. Helaman 6:9-11 is a virtuosic display of eModE and Hebrew poetics.

@Orbiting Kolob,

I implicitly said that I was speaking tongue-in-cheek. However, I would like to point out a that there are a lot of people, non-LDS even, that are finding problems with the peer review process.

There is a process called after publication review where any interested (qualified) party can provide a peer review of the article or whatever in question. In the case of Stanford Carmack's work on eModE in the Book of Mormon, it is available for anyone interested and qualified to review the process that Stanford used to arrive at his conclusions and to actually engage with the conclusions themselves. That has not happened thus far.

You also seem to be using a double standard for levels of evidence critical to the LDS scholarship, at least for yourself. You have asserted that Joseph could have produced the chiasmus in the Book of Mormon because he (a) was very familiar with the bible and (b) was trying to imitate Biblical language, etc. and thus unwittingly produced those structures. However you have produced no evidence to back up that assertion, and one poster has even pointed to a negative result when another author imitated the biblical language in "The late War" and did not really produce any chiasmus. I did look at you link, and I am glad that you said that the chiasmus was "invented".

You also keep harping on the eMode that Stanford has investigated as being part of the Texas Sharp Shooter syndrome. However, it has been pointed out several times that finding eMode in the book of Mormon, at the especially at the frequencies noted, was serendipitous. It was noted by Royal Skousen while working on his Book of Mormon Critical Text project and Stanford has followed up on that with his research.

Glenn

So Orbiting, let me see if I understand what you are proposing. Joseph Smith reads the Bible (I think that answers your first question), wants to imitate the language and "feel" of it so he unconsciously inserts chiasmus into the text. That is quite the claim. To back that up I hope you have solid evidence that doing that is possible. As pointed out by other commenters just because someone can write a couplet doesn't mean they can write a sonnet.

What you are proposing would be roughly equivalent to high school students reading Shakespeare's plays, wanting to write one of their own, and without thinking about it, even knowing anything about sonnets, manage to insert several sonnets into their play. If it is that easy then there should be loads of evidence of students, never having heard of a sonnet, but still suffered through Shakespeare's plays, managing to unconsciously produce sonnets in their writing.

The chiasmus in Alma 36 and in other places in the BoM are not random groupings of words that, if you squint hard enough and roll enough dice, form some sort of structure. They are comparable to the large chiasmus found in Deuteronomy 8 and Numbers 8 in that Bible. They are definite and objectively verifiable. If the chiasmus in the BoM are something that "anyone familiar with the KJV in the 19th century could have done", then there must be evidence of other people naturally producing chiasmus in their writing when they tried to imitate the Bible. Do you have evidence of that happening, or is Joseph Smith the only one? If he is the only one, then why is that? What made him special that he could do something that no one else had done?

As for your question about whether or not Joseph could read, if you were trying to make a point by asking the question, your purpose entirely escaped me. Quite frankly it strikes me as rather odd since whether or not he could read was ever in question. But there are several statements from Joseph Smith and others that he did learn how to read and write. I believe the earliest manuscript we have that was written by him personally is a letter dated "March 3th [sic] 1831". (btw, that letter is interesting because he misspells several words, the general flow is awkward and he manages to misspell Oliver Cowdery's name. Not really what you would expect from the word-smith (ha! pun!) that "wrote" the BoM.) Anyway, it is clear that by at least 1831 he could read.

I don't see any part of the Book of Mormon that could sustain the sort of argument Muslims have traditionally made for the Qu'ran — that it is writing too beautiful to be the work of any human being. So the question about Alma 36 is simply: Which human being wrote it? Joseph Smith (or some collaborator of his)? Or Alma? If Alma could have written it, why couldn't Smith?

What advantages would Alma have had over Smith, that would have helped him to write chiasms?

Alma (if he existed) might have been steeped in Hebrew literature; but Joseph Smith was more steeped in ancient Hebrew literature than any Nephite could ever have been. Smith had the whole Hebrew Bible, and he heard it all his life.

It's not clear that Alma would have been any more consciously aware of chiasmus as a literary device than Smith was. Alma didn't have a PhD, either. There's no reason to think that any ancient poets knew the terms that later critics would apply to their technical tricks. Homer wrote no footnotes about synecdoche.

If Alma would nonetheless have known enough to aim at chiasmus because it would make his writing sound nice, Smith could have reached that same knowledge, too, just by hearing enough Old Testament.

Of course it's one thing to have the goal of chiasmus, and another thing entirely to achieve the goal well. But beyond the mere intention of trying to work in some reverse repetition, the tricky work of actually pulling it off would have been no easier for Alma than for Smith. If Alma could do it, why not Smith?

@ Jack: I agree, it sort of is "damned if you do and damned if you don't." But to me it doesn't seem that critics are inconsistently making Joseph Smith out to be both idiot and genius. It's that Mormons are exaggerating Smith's achievement, in order to make it seem superhuman, and so support his claim to be a prophet.

When critics perceive his achievements as much less than that, Mormons counter that his achievements were far too great for an average guy. But 'either true prophet or stupid bumpkin' is a false dichotomy. The truth is somewhere between those distant extremes. So Smith was much less brilliant than a historic genius, but much smarter than an average schmoe. That's the damned-both-ways, as I see it.

In fact this is the problem with the whole premise of apologetic arguments that are based on the extraordinary nature of the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon is extraordinary, but only so far. Only one person in a hundred could have written anything like it; or maybe one person in a thousand, or in ten thousand. If you don't believe that, well, maybe you just don't know enough people. I really don't see the number going as high as 100,000.

One-in-ten-thousand may sound like impressive odds … but this is once again a Sharpshooter Fallacy. We didn't pick Joseph Smith out at birth, by random, and then find that he produced the Book of Mormon. Instead we waited until the whole religion-drenched Burnt Over District of early 19th century New England produced a successful sect founder, and then we looked at the book he produced to found his sect. We let history sort through a few hundred thousand people for us. It's no great wonder if the person it found was a remarkable guy.

But how common have true prophets been, in the past millennium? Even one-in-a-million is surely too high a rate. Probably one-in-a-billion is closer — if that.

So all the Mormon apologetic arguments about how remarkable the Book of Mormon is, as a book, amount to this:

1) Not a man in ten thousand could possibly have faked the Book of Mormon!

2) Therefore Joseph Smith must have been a man in a billion!

Now that we're talking seriously about statistical fallacies, I hope the gap in this argument is clear. The gap is just too wide. Smith was no average guy, but neither was he one-in-a-billion.

Anglin, you're out of your depth here, despite your apparent sincere earnestness. Your numbers are mild and #2 above is not what apologists claim. The event was controlled by deity, and another conduit could have been used.

James,

There's a much simpler explanation: The Book of Mormon is what it claims to be.

Jack

James,

Alma was the designated record keeper of his people. And as pointed out by Jeff there are three versions of his conversion recorded in the BoM. The first two are loose and more along the lines of "here's what happened", while the third recorded in Alma 36 comes late in his life after he presumably had time to develop it into a complex structure. (As a side note, that indicates a natural progression from young man and convert to mature scholar without explicitly mentioning it or talking about it, something you would expect from a historical document and not from a spontaneously produced narrative.)

To say that "Joseph Smith was more steeped in ancient Hebrew literature than any Nephite could ever have been" is quite a stretch since Alma presumably learned Hebrew and was the designated record keeper, while Joseph Smith only began to learn Hebrew years after publishing the BoM.

As for your claim that there are many people who "could have written anything like it", where is the evidence? If there are so many people out there who could have done it, why haven't they? If 1 in 10,000 could have done it then at least some of the 12+ million people in the US in 1830 should have written something comparable. If it were possible, then statistically there should be several books equivalent to the BoM. Where is your evidence? To use the Texas sharp shooter analogy, where are all the other bullet holes? If you claim that it is nothing special, then you have to show that there are others like it.

Hi James,

Taking the humanist approach that you have started. Take it a step further now using the numbers you have produced. Let's say 1 in 10,000 could produce a book similar to the Book of Mormon, couple that with the odds of a successful sect leader coming around. What are the odds of those two combined? And, still with the humanist approach that you are taking, I would argue that 1 in 10,000 is still too low for the Book of Mormon given that there are millions of people who have been converted because of the book. How many books have produced those kinds of numbers?

So, the combination of a successful sect leader coupled with a book that has managed to convert millions, I think we have found our 1 in a billion person.

Steve

James,

I've mentioned this before, but there is an interesting hypothesis as to why Alma might have been able to produce chiasmus, and Smith would not. I think many of us Mormons at least accept the possibility that the Book of Mormon took place in Mesoamerica. Interestingly, the Maya document Popol Vuh contains various instances of chiasmus, some fairly complex (see here. If there was any connection between the Maya and the Nephites, then it seems plausible that Alma, who kept records, may have been trained in that form of poetry. Even if he called it something else. On the other hand, I can see little reason to believe that Smith should have been trained in any ancient Hebrew poetry. The point that he was familiar with the Bible has already been addressed, but just because I've read Shakespeare doesn't mean I will be unconsciously write in iambic pentameter while trying to emulate him, particularly if iambic pentameter has not been identified as a major part of Shakespearean texts. There's my two cents.

@Quantumleap42:

I realize that Smith didn't know the Hebrew language when the Book of Mormon appeared. But the Book of Mormon (as we have it) isn't written in Hebrew. The kind of steeping in Hebrew literature that one needs, in order to write chiasms in English, is just steeping in Hebrew rhetorical structures, not steeping in Hebrew grammar and vocabulary. Rhetorical structures like chiasmus survive translation very well, or we wouldn't be having this discussion. The English Bible with which Joseph Smith was surely familiar provides plenty of steeping in Hebrew rhetorical structures like chiasmus.

I suppose it's conceivable that the Nephites either preserved or created a larger body of Hebrew literature than the Old Testament, which was subsequently lost to history, and Alma got steeped better from this larger literature than Smith got steeped from just the Old Testament. This would be pure speculation, however. If we disallow arguments based on pure speculation, then my claim that Smith was more steeped in Hebrew rhetoric than Alma could have been would have to stand.

And even if we allow speculative hypotheses about Alma's superior steeping, it's still not clear that only Alma could have been steeped enough to manage Book of Mormon chiasmus. Even Smith's weaker steeping, in just the Old Testament, would have been sufficient, because if the Old Testament weren't sufficient to convey the idea of chiasmus as a thing to do if you want to sound Biblical, then no-one would ever have claimed chiasmus as a Hebraism, and we wouldn't be discussing it.

@Ryan:

It's interesting that Mayan literature also uses chiasmus. In fact a lot of literatures do, because chiasmus is a pretty simple device, at least until you start building it up to seven layers or whatever.

But that's why the notion of being trained in chiasmus seems weird to me. On the one hand it seems to me that no great training is needed, just to get the basic idea. And on the other hand it's not clear to me that any amount of training is going to make it easy to construct large and complex chiasms. You're still going to have to hammer out the particular text, and manage to make it seem coherent and not too awkward.

So I still just don't see how even a Mayan cultural context would have made Book of Mormon chiasms substantially easier for Alma than they would have been for Joseph Smith.

This comment has been removed by the author.

Ryan writes, just because I've read Shakespeare doesn't mean I will unconsciously write in iambic pentameter while trying to emulate him….

Actually, I bet you probably would imitate his iambic pentameter.

But anyway, suppose the following were to apply:

(1) Mr. Jones is very familiar with Shakespeare, in fact, more familiar with Shakespeare's works than any other text; and

(2) Mr. Jones does not normally write or speak in iambic pentameter, and furthermore has never even heard the term "iambic pentameter"; and

(3) For whatever reason, Mr. Jones writes a text using a lot of iambic pentameter.