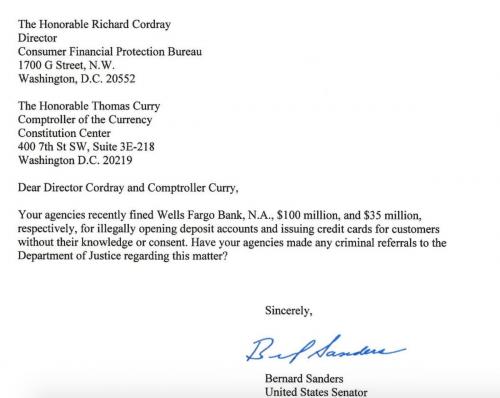

Latter-day Saints often need to discuss or defend LDS teachings about the potential of sons and daughters of God to become more like him (our version of theosis, which we feel is on solid ancient ground with strong ties to early Christianity). A commonly used passage in such discussions, a proof text, is Psalm 82:6, “I have said, ‘Ye are gods; and all of you are children of the most High.'” Christ quotes this in John 10:340-36, a passage we commonly use as well:

34 Jesus answered them, Is it not written in your law, I said, Ye are gods?

35 If he called them gods, unto whom the word of God came, and the scripture cannot be broken;

36 Say ye of him, whom the Father hath sanctified, and sent into the world, Thou blasphemest; because I said, I am the Son of God?

These are interesting passages indeed, but the source, Psalm 82, raises some questions since the context doesn’t fit neatly into the LDS position. Who are these people being called “gods” and why are they being condemned? Doesn’t sound like such a great thing for actual exalted beings, right?

The gritty details of Psalm 82 and its relationship to the words of Christ in John 10 are explored in detail by Daniel O. McClellan in “Psalm 82 in Contemporary Latter-day Saint Tradition” at Mormon Interpreter. This is the most thorough and satisfying discussion I’ve seen, yet it will leave some of us unsatisfied since it becomes clear that there is not a neat resolution in the “non-harmonizing perspective” provided by McClellan. But understanding Psalm 82, both what it might have meant to its author and the different way it may have been understood and applied in New Testament times will help all of us better understand how these verses relate to LDS theology.

Here are McClelland’s concluding remarks:

So this brings us to the final question. If we understand John’s

description to be a verbatim account, is Jesus misusing scripture by

reinterpreting Psalm 82? I suggest he is not. I believe Jesus is doing

what all scripture-based religious communities do, namely reading

scripture in a way that makes it applicable to their time. He likens the

scriptures to his own day, to paraphrase 1 Nephi 19:23. In John 10, the

reference to Psalm 82 refers to foundational narratives in the Jewish

community’s shared identity, namely the Exodus and Sinai traditions.

Peterson and Bokovoy do the same thing in proposing that Psalm 82 can be

ideologically linked with Abraham 3’s council in heaven. This is a

Latter-day Saint foundational narrative. When we can tie texts like

these to our own communal narrative, we strengthen our community’s

identification with sacral past and utilize that past to inform our

present experience. This makes the scriptures a dynamic tool, not just a frozen text.

On a literary level, Jesus’s defense here has a wider rhetorical

purpose, as well. Not only does he identify himself as one of the Jews

by appealing to a shared understanding of the Psalm’s meaning, but by

appealing to that tradition, whereby those who received the word were

made divine, the author reminds the reader/listener of a promise made a

few verses earlier (John 10:28): “I give to them eternal life, and they

shall never [Page 96]perish.” John 1:12

is no doubt also in view here: “as many as received him, to them gave he

power to become the sons of God.” John’s message is this: The

Israelites were briefly made immortal and thus divine by the reception

of God’s Word. The Word is now incarnate among you, and he is inviting

you to receive him. John 10:34–36 and Jesus’s appeal to Psalm 82 is not

just about Jesus’s divinity, it is also about the divinity of those who

hear and believe.

Yes, an interesting text indeed, and not just for reminding us of the Canaanite-ish henotheism of early Judaism.

I would say that Psalm 82 poses a distinct challenge to the LDS notions of exaltation. On the one hand, it confirms the existence of other gods. On the other hand, it depicts God as criticizing those other gods for being unjust. But how could other gods possibly be unjust? Wouldn't they have to have advanced way beyond that possibility in order to enter into their exaltation in the first place?

So, sorry, but Psalm 82 is hopelessly at odds with LDS doctrine.

Another question, Jeff — why do you use the euphemistic phrase, "the potential of sons and daughters of God to become more like him"?

Why not refer simply to our potential to become gods?

After all, this is the language used in Doctrine and Covenants — both the D&C text itself ("Then shall they be gods") and in the Church's headnote ("Celestial marriage and a continuation of the family unit enable men to become gods").

There's a significant difference between becoming a god and becoming like god. Why the misleading euphemism?

OK

And from my understanding of Eastern Christianity's concept of theosis, this 'significant difference' that you point out makes all the difference. Theosis, again from my understanding, is not about human essence being transformed into divine essence, which is what Mormon exaltation is all about. In theosis, a human being will never be made a partaker of the divine essence. He/she remains human. There is a distinction made between species, in a way. God and human beings are of a different species. In Mormonism, humans are of the same species as God, but just in an embryonic state, so to speak.

Becoming more like God is not just a euphemism, it's the most accurate way to describe what I believe is meant by LDS doctrine and the scriptures. Sons and daughters of God grow up to become like what? Like God. That's Paul's message in Romans 8, where sons of God can become joint-heirs with Christ (vs.14-17), "glorified together" (vs. 17), with "glory which shall be revealed in us" (v. 18). In the end, "we shall be like him" (1 Peter 3:2 and Moroni 7:48).

In ancient days, those familiar with the Jewish/Near Eastern concept of the divine council (council of the gods) might have had less trouble with the appellation "gods" to describe our divine potential. They might have understand that while there is only One God, God the Father, as far as we are concerned, yet there could be, as Paul put it, "gods many and lords many" (1 Cor. 8:5-6). But while the Old and New Testament don't have any trouble using the term "gods", in our era especially it might cause potential for confusion and misunderstanding since people might think it's a reference to replacing God or becoming God, the Creator of the Universe, which, for the record, has already been created.

LDS doctrine teaches that we are now and forever will be subservient to Christ and to God, and that we give him glory forever (D&C 76:92-93), serving as priests and kings, priestesses and queens to God, who shares all that He has with us.

Becoming "gods" means becoming like God, united with Him, sharing in eternal life, and fulfilling the promise to become one with Him, as Christ prayed for Christians to do in His great intercessory prayer in John 17. Describing all that as becoming like God, or more like God (since we are already created in His image and already like Him in a sense), is the terminology that I feel is more appropriate for our day. Early Christian writers used "gods" rather heavily, though.

Beings who become divine or "like God" can be called "gods" in the Bible and in early Christianity. These subservient beings are like God in at least some ways. If you meant to say that there is a significant difference between becoming like God and being God, I fully agree!

We are His creations. We are the fallen, dingy men He rescues, just as Christ, His perfect Son, is the sinless Redeemer who frees us from our sins. We are the children, given all His gifts, but not replacing Him or taking His place. So yes, we can, though His grace, become more like Him, and He urges to become joint heirs with Christ (Rom. 8), to become one with Him (John 17), and even to sit with Christ in His throne (Rev. 3:21). This is not completely unrelated to Christ's use of Psalm 82:6 in John 10, where, as McClelland notes, it is ultimately about the divinity of those who accept the Word of God.

Is becoming like Him in the Kingdom of God just a metaphor with little meaning since God is "wholly other", a completely different species? Are we His sons and daughters only in a remote figurative sense, like a good waffle is the "child" of, say, the Waffle King (shout out to Weird Al)? If so, it might be blasphemous to speak of being His children in anything but a figurative sense. If so, it would be ridiculous, as EverythingBeforeUs suggests, to think that humans could somehow put on the divine nature: "a human being will never be made a partaker of the divine essence. He/she remains human.".

I suggest that putting on the divine nature, becoming partakers of the divine nature, is what original Christianity seeks to do. Peter's words might help you appreciate this. Please read 2 Peter 1, who tells us that God has given us all things that pertain unto life and godliness (vs. 3) and has called us to glory and virtue (makes sense if we are on the path to becoming more like Him, the source of all glory and virtue). Through Christ, we are given "exceeding great and precious promises: that by these ye might be partakers of the divine nature" (vs. 4).

Partakers of the divine nature. Wow. An overwhelming concept, I admit, but entirely biblical. It's possible because God is not "wholly other" as defined by modern theologians; He is not of a completely different species. He is our Father in Heaven, the "Father of spirits" (Heb. 12:9), with Whom we can become one as Christ is One with the Father, if we are to believe the word of the Son in John 17:11-13, 21-23).

His Son, Jesus, shows us the connection between humanity and deity. Christ came as a human and resurrected as divine Man–a divine Human. In the image of His Father. Paul did not hesitate to call Christ "man" (Romans 5:15, 1 Cor. 15:21), even "the man Jesus Christ" who stands as mediator between God and men (1 Tim. 2:5). The man Jesus Christ is, obviously, the same species as God. His path points to our potential, our divine potential through Him. This is the message of Christianity. Early Christianity, at least.

The man Jesus Christ is, obviously, the same species as God.

If Jesus was the same species as God, and Jesus is the same species as humans, then God and humans are the same species. However, our species evolved on Earth a few hundred thousand years ago. Does that mean that God didn't exist before that?

Good grief, Jeff — what a timid reading of D&C 132. It leaves me wondering why an outsider like me should be a better reader of the plain meaning of Mormon scripture than some Mormons themselves. (Perhaps the reason is my immunity to any desire to soft-pedal Joseph Smith's more radical doctrines. I have no reason to set out the milk before the meat.)

Mine is not a hard case to make. LDS doctrine takes literally the notion that God is the father and we are the children. Right? Right. Let's run with that. What do we say when the child grows up, reaches maturity, starts a career, gets married, has children?

Do we say, The child has become like an adult?

Of course not. We say, simply and accurately, The child has become an adult.

Children become adults, and in precisely the same way, in Mormon theosis, do men become gods. Children become adults because they acquire the attributes that define adulthood, and men become gods because they acquire the attributes that define godhood.*

That's why D&C 132 says this:

Then shall they be gods, because they have no end; therefore shall they be from everlasting to everlasting, because they continue; then shall they be above all, because all things are subject unto them. Then shall they be gods, because they have all power, and the angels are subject unto them.

To be above all, to have all things subjected to one, to have all power — what are these, if not the attributes of godhood?

Quite rightly does this passage plainly, directly, and repeatedly use the phrase shall be gods.

Of course, children always remain in some ways subordinate to the adults who preceded them in attaining adulthood. The son is always in some way subordinate to the father, and the father to the grandfather, and so on. But this in no way changes the fact that the son, in addition to becoming "like an adult," becomes an adult, full stop. In the same way, the fact that there is an unalterable hierarchy of gods, and that the exalted man will never sit at the top of the heap, does not change the fact that what exaltation makes of that man is a god.

How can you possibly read Smith any other way?

* Of course, the phrase "like a god" is literally true. Obviously, a man who has become a god has also become "like a god." But this is so only in the trivial and misleading sense that a man who has just died has become like a corpse.

Jeff,

LDS doctrine is that you will be exalted, become a God, continue to create spirit children with your eternal wife or possibly wives, create earths, populate other planets with your children, and then they too will be exalted, and the process begins anew. This is Mormon doctrine. You can shroud your words in the language of Christianity if you like, but this is really what Mormonism is all about.

Who are the sons of God? Not every single human being. Paul's doctrine of the adoption is very clear that those who becomes children of God through adoption are those who believe in the name of Christ. Christ is the only-begotten Son of the Father. We, through receiving the Son by the power of the Spirit, become joint-heirs through adoption. Why adoption? Aren't we children of God from the first moment? No…we are not of God's family until we are adopted. We are joint-heirs with Christ through adoption only. This is Romans 8.

Why were the Pharisees so outraged when Christ declared he had come down from above? Because the Bible also teaches that we human beings are from here below. We did not descend from above. So for Christ to make this statement, it was quite scandalous. He was saying that he was with the Father. Which means he was something more than human. And the Pharisees knew what he meant.

This makes sense in the context of Paul's doctrine of adoption. If we had all come down from above, we'd all have claim to a place in the family of God. But we don't, because we are not heavenly, but of the earth. That is why we need to be changed by the Spirit to become members of God's family through adoption. We are not by birth a member of such a family. We must be adopted into it.

1 Corinthians 8: The "gods many and lords many" that Paul is referring to here are false gods. Paul is talking about the morality of eating things sacrificed to idols. Context. Always the context.

P.S. To be "above all," to have all things "subject unto" one, to "have all power," and so on — these are the attributes that define godhood in D&C 132. Are they also the attributes of godhood in the mind of Joseph Smith?

Note the attributes of the Judeo-Christian God that are missing from D&C 132. Godhood is not delineated there in terms of justice, say, or mercy, but in terms of status and power. Whether we can attribute this to Smith's evident megalomania and/or his power within the Church is a question I'm interested in exploring.

Jeff,

You write that we are God's creations. But in Mormonism, we are not technically God's creations. We are co-existent with God. We were eternal intelligence. God created us in the sense that he changed us into spiritual form. Then we are placed in mortal bodies later. But our intelligence, that unique aspect that makes us us, was always in existence. Thus, despite what the Bible says, God is NOT the creator of all things both in the heavens and on earth. This is kind of a heretical concept, because if I am in some way co-existent with God, then there has to be something greater than both God and me by which we have been sustained. Something else besides God has provided our life source, or our source of existence. Think about it Jeff, if you were an intelligence eternally existing, by what power were you existing? Were you self-sustaining?

In Christianity, God is the self-sustaining source of all existence. The "unmoved mover." God is literally the source and origin of everything.

If the Mormon God is not the source of this existence (and he can't be, for he was once a man, remember), then the Mormon God is not God at all, because in the Bible, God is described as the source of everything.

Mormons have a God much more similar to God as described by some of the Gnostic sects. He is a lesser deity who was given charge of organizing the earth. Strangely, in some Gnostic legends, this lesser deity is the Satan figure. He is the vindictive bad guy who is thwarted by the real Supreme God, who sends Jesus to foil the bad deity's plans.

Orbiting Kolob,

You say, "Note the attributes of the Judeo-Christian God that are missing from D&C 132. Godhood is not delineated there in terms of justice, say, or mercy, but in terms of status and power. Whether we can attribute this to Smith's evident megalomania and/or his power within the Church is a question I'm interested in exploring.

I say, "Nice catch." This dovetails nicely with something I've been thinking about lately. I believe that the rewards of Heaven that we will receive is the love and the goodness we have shared in this life. We take that love and goodness with us, and if we have learned to rejoice in love and goodness, than Heaven will be beautiful. But in Mormonism, the rewards of Heaven are kingdoms, powers, principalities, wives, children, eternal increase (sex), and authority. Sounds kind of Devilish to me.

In my strange little world, we say the child becomes like his father, not that the child becomes his father. In the case of God the Father, it's important to note the difference between the supreme God of gods and Lord of lords (as Moses put it in Deut. 10:17) and his imperfect, created children who can become like Him through His mercy and grace.

I have "gods" in the title, so it's obvious that "gods" are part of this discussion. But if it weren't for capitalization conventions in titles, it would be lowercase "gods" to emphasize that these are beings who are like God, but not Him, not replacing Him, not superior to Him, but eternally subservient to Him, the Creator and Father, and to His Son, the Savior. To me, it's clearer to explain upfront that it's about becoming like Him.

Yes, as many early Christians taught (see the Patristic Writings section of Wikipedia on Divinization for a few of many quotations), we can become "gods", as we become like (in some ways) God the Father and His Son Jesus Christ.

Yes, there is some part of us that is co-eternal with God. We don't understand what that is or how it works, but we understand that this may be part of what really gives us free agency versus being entirely programmed by God to choose good or evil. But He remains our Creator and Father. Whatever glimmer that intelligence is, it is through God's creation that we were formed into spirits and mow living, mortal beings, and given the gifts of agency, of the Atonement, and of resurrection, etc. We are entirely dependent upon Him, though our decisions for good or bad are not entirely dependent on Him and it is therefore not unfair that we are held accountable for at least some aspects of what we choose.

OK, Jeff — I guess I understand your rationale for saying "like God" instead of simply "gods." But the fact remains that either God or Joseph Smith (take your pick) felt it wise to use the more straightforward and less misleading terminology. And sorry, but I still see your preference as a matter of "milk before meat" euphemism rather than accuracy. Perhaps I think this way because I watched Gordon Hinckley work so pathetically to evade the truth during that Larry King interview. ("I don't know that we teach that." Really? You don't know your own basic doctrine? Amazing. And obviously an attempt to keep the doctrinal meat off the table.)

ETBS, I think you're quite right about the Gnostic elements of Joseph Smith's theology — great observation.

very one, allow me to expand a bit on the Mormon focus on power at the expense of other considerations. Ask yourself this: does the Church have a detailed theology of things like morality and justice? Nah. But has the Church worked out in great detail the niceties of its earthly power? You betcha.

Think about just one of the perplexities of being a moral person in our modern world: the fact that one's retirement dollars are routinely invested, usually without one's knowledge, in industries that employ slave labor. In such a world, is there a moral obligation for the individual to dig into the details of one's retirement account and divest from certain companies? What if one's retirement portfolio is managed collectively by one's employer? Is there a moral obligation to persuade one's employer to divest? Or what?

About this sort of thing, the Church has nothing to say. It's just not on their theological radar.

To the LDS Church, morality and justice have no social or political or economic dimension at all. Morality is resolutely individual and personal (and furthermore largely concerned with personal sexual morality). It's just an incredibly crude approach.

But when it comes to who has the authority to excommunicate whom, and the differences between excommunication and mere disfellowshipment, and the procedures for maintaining a temple recommend — in other words, with the detailed mechanics of the Church's own earthly power — they've got it all worked out. They've obviously given it a LOT of thought.

It's a strange set of priorities, especially given the prominence of fierce justice-warriors like Isaiah in the Book of Mormon.

I dunno — maybe it gets back to the belief that the Church's earthly power (as the Kingdom of God on Earth) will be the instrument by which morality and justice ultimately triumph.

EverythingBeforeUs said: in Mormonism, the rewards of Heaven are kingdoms, powers, principalities, … and authority. Sounds kind of Devilish to me.

I'm sorry some passages in the LDS canon discussing the next life give you such negative feelings. I'm wondering, though, how you approach related passages about reigning, ruling, thrones, etc., in the parts of our canon that include the New Testament? Some examples:

"And hast made us unto our God kings and priests: and we shall reign on the earth." (Rev. 5:10)

"To him that overcometh will I grant to sit with me in my throne, even as I also overcame, and am set down with my Father in his throne." (Rev. 3:21)

"Blessed and holy is he that hath part in the first resurrection: … they shall be priests of God and of Christ, and shall reign with him a thousand years." (Rev. 20:6)

"And hath made us kings and priests unto God and his Father; to him be glory and dominion for ever and ever." (Rev. 1:6)

I trust you don't get that same unpleasant feeling as you confront those passages.

Fortunately, to your point, I think heaven isn't just about responsibility and the heavy duties and burdens of being kings and queens to God and sitting with Christ in His very large and imposing throne. Joseph taught that "The same sociality which exists among us here will exist among us there, only it will be coupled with eternal glory, which glory we do not now enjoy." (Doct. & Cov. 130:2) Those who, through the Atonement, become more like Christ will have the kind of kindness and charity needed for it to truly be heaven. We will live together, learn together, rejoice together, love one another as friends and family (yes, even in family units – I hope that isn't offensive to you, but you expressed it as if it were), and have a marvelous adventure. Eye hath not seen and ear hath not heard how endlessly cool it will be. We know almost nothing of how it will work and what it will be like, but we can look forward to it. In spite of our uncertainties, potential discomfort, and abundant misunderstandings, there is no real basis to brand the infinite blessings of God to His children "devilish." Recognize that that which confuses and offends may be completely misunderstood.

This comment has been removed by the author.

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

Orbiting, I'm surprised by your latest jab: "To the LDS Church, morality and justice have no social or political or economic dimension at all." I must be grossly misunderstanding, sorry, but to me, it seems like you are saying that to the LDS Church, morality and justice have no social or political or economic dimension at all. Maybe I'm just reading you too literally? Because I don't think someone familiar with the Church would say that seriously, even if that person is on a mission to belittle the Church at all costs.

When I was a bishop for a while in Wisconsin, that biggest demand on my time and energy was not in disciplining people–a minor area, actually–but in overseeing the social and economic aspects of service in the Church. It's a fundamental part of LDS morality and our relationship to God. We had a lot more training on those areas than on the other administrative issues you complain of.

The welfare system of the Church is internationally recognized and respected by those of good faith and open minds. It is one of the most visionary and remarkable things about the Church. It eats up a lot of the energy of its leaders. The service requests and opportunities eat up vast amounts of time and money from its members. In addition to organized efforts like service projects, the fast offering program, and humanitarian relief, add the personal ministering of home teaching, visiting teaching, and random personal acts of service as members respond to the needs around us on their own.

The economic aspects of the LDS approach to life include the generally well-known LDS emphasis on food storage and emergency preparation, which has allowed many LDS families to help others in times of need and to care for their own needs, of course. LDS emphasis on these economic issues allow the Church to organize and bring relief faster than the Red Cross does when trouble strikes in areas where we have members. It's impressive to see this in operation up close, as I did in Homestead, Florida years ago after a hurricane hit that community, while I was living in Atlanta. I was part of the relief efforts for a while and it left a lasting impression on me. Just amazing to see how it can work.

In fact, a key aspect of LDS sensibility and our world view is a close integration of our economic life with our spiritual life. Alleviating poverty, helping people get education, lifting people toward increased self-reliance, selflessly giving of our means, that's all part of LDS life. From the earliest days of the Church, building and irrigating and gardening in the dirt around us is part of our approach to preparing for heaven. We cannot build Zion without attention to the economic issues around us. Sorry we haven't done it in the trendy ways you would like, but we're doing far more than you see (or are willing to see).

In the last Sunday School lesson I attended, we had an inspiring discussion about caring for the poor, including the practical issue of dealing with beggars. I was deeply impressed with the compassion I learned from others in that discussion. These social and economic topics are big deals in the LDS experience. "Caring for the Poor and Needy" is a big section with extensive resources at LDS.org. it's a frequent topic in lessons, conference talks, and in the LDS scriptures (Mosiah 2 in the Book of Mormon being especially noteworthy). It's part of the law of consecration. It's a big deal. Definitely on the LDS radar screen.

There is constant emphasis on the very things you say aren't even on our radar screen. I think your bitterness over our social and political efforts touching upon marriage/family issues have so enraged you that you are blind to what the Church really is. That's too bad, really.

To the person whose comment I just deleted: this post is not about polygamy. Nor is it about sex. Please remember you are a guest here. What I consider to be cheap, bitter shots against my faith are for a different forum, please.

The boorish behavior of the critics is tiresome, and a complete waste of time.

Hi Jeff — I see that I haven’t been very clear on what I meant by "morality and justice have no social or political or economic dimension at all." In fact, I expressed that terribly. My apologies.

In order to explain what I meant, let me backtrack a bit. I can’t seem to do this and stay under Blogger’s 4,096-character limit, so this will be a two-part comment.

First Part: The background for me is that I've been reading up on a debate that followed the publication of Hannah Arendt's famous Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil. Part of that debate concerned the extent to which one should believe Eichmann's claim that he was not really antisemitic. But lurking behind that question was a larger one, a question with implications not only for Eichmann and the Nazis, but for all of us: the question of what to do when evil is so deeply woven into one's social and economic system that it becomes difficult or impossible to live and work in that socioeconomic system without participating in that evil.

Eichmann claimed he was not particularly antisemitic; he was simply a guy doing a job that just happened to be integral to the mass killing of Jews. He had no personal desire to kill Jews, but, like any conscientious and ambitious employee, he did want to his job as well as possible and advance his career. In this view (which of course Eichmann had every reason to advance regardless of whether it was true), he was not personally guilty, he was an innocent man working in a guilty system. (Of course, most of us would argue that Eichmann was guilty of mass murder regardless of his personal feelings toward Jews; he knew perfectly well the result of his work and was morally obligated not to do it.)

The larger question is, are we all in some sense in the same situation as Eichmann? Should we at least seriously consider this possibility?

(Yes, Eichmann's argument was almost certainly totally bogus, but that doesn't mean the above questions are not worth asking, and it doesn't mean that the answer to them must be "No." And yes, I'm perfectly aware of the danger of making Nazi analogies. I'm not trying to suggest that our society is as bad as Nazi Germany. Eichmann serves as a good example not for reasons of parity, but for reasons of clarity: his case makes the issue crystal-clear.)

For us, the general questions unfold more or less like this: is it possible that we too are "innocent" participants in a "guilty" system? If the system includes horrific evils, and we know about them, can we even be considered "innocent" at all? Things might be different if one lives in a dictatorship where one cannot change the system, but if one lives in a democracy, should it be considered a moral obligation of citizenship to ferret out any evil embedded into the socio-economic system and perhaps work toward eliminating them?

As I put it in my comment above (to which you understandably objected), "Think about just one of the perplexities of being a moral person in our modern world: the fact that one's retirement dollars are routinely invested, usually without one's knowledge, in industries that employ slave labor. In such a world, is there a moral obligation for the individual to dig into the details of one's retirement account and divest from certain companies? What if one's retirement portfolio is managed collectively by one's employer? Is there a moral obligation to persuade one's employer to divest? Or what?"

These are the kinds of questions about which I think "the Church has nothing to say." And, as I hope I have now made clearer, these kinds of questions are not really answered by references to food storage and the Church welfare system.

Second Part: Suppose for the sake of argument that Eichmann was right about himself. Suppose he had nothing against Jews, that in fact he was a pillar of racial and religious tolerance. Suppose further that he dedicated a portion of his income to charity, and that once a week he volunteered to feed the homeless, and so on.

Suppose all this were true, but that he also went to the office every day and did his best to carry out the Final Solution assignments given to him by his employer. In other words, suppose that he was personally quite moral, but he he had a job that had monstrously immoral consequences.

Is he not still guilty? Do his personal virtues of tolerance and charity in any way absolve him? Were he to say, “You can’t hang me – I feed the homeless!” would we put away the rope? And were he to say, "Well, I didn't know about the consequences of my job, would we not say, "Well, you should have known — the signs were all around you, you should have heeded them, you should have made some effort to find out whether the rumors you were hearing were true"?

And if we believe such things of Eichmann, should we not believe them of ourselves as well? Yes, yes – I agree, it's pretty unlikely that any Nazi-level evils are systemic to our own socio-economic system. It's pretty unlikely that any of us, in the course of simply going to the office and doing our job, are as guilty as Eichmann — but still, there are some pretty gruesome things happening out there, and the history of the Industrial Revolution was horrific enough to give us pause about what we might be doing today in the process of economic globalization – so shouldn't we make an effort to find just what we might be guilty of, to do so now rather than leaving it up to the historians? To examine whether there is any kind of evil woven into our own system, and think about how we ought to respond to it?

That is, do we have a moral obligation to attend to the questions so many people have been raising about what they variously call "systemic evil" or "structural evil"?

I can think of plenty of Jewish, Catholic, and mainline Protestant theologians who think and write about these questions, but not any Mormon theologians. Maybe I'm missing something, but these kinds of questions just seem alien to Mormon thought.

Paralyzing overanalysis; our every act can be construed as evil. We must snuff out our own lives to save Gaia and every innocent who gets maltreated by advantaged heteronormative human action.

Anon 12:20, there are some who accuse the Church of promoting anti-intellectualism ("the mantel is far, far greater than the intellect," etc.). I don't believe it, myself — but that's in spite of, not because of, inane comments like yours.

So you are dissing the Church this time because it doesn't meddle enough in people's private lives? Or is just that you want the meddling to be in trendy Lefty ways–ignoring the systematic evil of abortion and the exploitation/degradation of women in pornography, while wringing our hands over the possibility that a percentage stocks in our retirement account's index funds might be tied to those who are unenlightened about global warming?

The Church takes strong stands on a variety of moral issues, but teaches people to be actively involved on their own in good causes. It generally leaves the details to us about how to do good in a complex world filled with evil that needs our attention.

Jeff,

Good post. I appreciate when we can set the record straight on some of our misunderstandings of scripture. I also appreciated your comments, especially at 6:46 AM, May 24, 2015.

Of all the doctrines in the church, this one resonates the most with me and answers life's biggest questions in a way that no other philosophies do. It's so interesting to see adherents to other philosophies fight so hard to divorce themselves from the divine nature that Christ himself identified within us and that his apostles alluded to so many times.

"LDS doctrine is that you will be exalted, become a God, continue to create spirit children with your eternal wife or possibly wives, create earths, populate other planets with your children, and then they too will be exalted, and the process begins anew. This is Mormon doctrine. You can shroud your words in the language of Christianity if you like, but this is really what Mormonism is all about."

I don't see this as anything more than Mormons taking an original Christian doctrine like theosis and speculating (or in the case of J.S., revealing) further until it reaches its logical conclusion–limited though it is.

Anon 7:00, given that abortion has not gone away over the years and the "exploitation/degradation of women in pornography" has only gotten worse, despite the Church's moralizing against them, maybe the Church should be thinking about these things in new ways.

As your response suggests, the Church currently does not think of these things as systemic, but as the result of individuals making bad choices. Of course, people do make choices, but they do so within systems that can heavily influence those choices. Please remember that by systemic I mean not simply "widespread," but "embedded in a system in such a way as to result from otherwise good people performing their ordinary, everyday, rational activities." If you don't care for my Eichmann "banality of evil" example, then consider the example of what's called the "tragedy of the commons." And if you don't care to think systemically about global warming, you (or the Church) might still consider thinking systemically about other issues.

I'm not sure that lefties are the only ones who think systemically. Right-wingers also do so, as when they argue for things like market-based education reform. I don't see why the Church couldn't think systemically about abortion and pornography and its other issues of concern. There's no need to reduce this discussion to a typical knee-jerk internet argument of liberal vs. conservative. It's a little more meta than that.

Pierce, I think you've put your finger on the key differences between LDS thought and mainstream Christian thought, or at least the aspects of Mormonism that most disturb mainstream Christians. I would say, though, that it's not theosis and continuing revelation per se that bother traditional Christians — it's the dynamism and open-endedness that lay behind them.

Perhaps no one here will believe this, but I have tremendous admiration for Joseph Smith (not that I don't also consider him a scoundrel). To me he was not so much a prophet of God as a prophet of America. He created a theological vision of limitless human possibility (in religious terms, "theosis") that was very much in tune with the boundlessness and optimism of the early American republic.

Traditional Christianity says we live, we die, we wind up forever in heaven or hell, and that's it. We might be eternally happy or eternally tormented, but all change and growth and novelty have basically ceased. This view is not only very dull (as many critics have noted), it is also limited in its view of human possibility. The best we can ever hope to be is a happy little vassal in some other being's heavenly realm.

That very much runs counter to the democratic vision that was emerging in this country's early republican era. Democracy was held to be good not merely because it proffered freedom, etc., but because it promised to fully unleash human possibility, to allow people to attain their full potential. What might that potential ultimately turn out to be? No one could really say, since humanity had never before lived in a society that might allow it to be realized. Human potential had hitherto always been stifled by undemocratic social and political systems.

This sort of thinking was in the air in the early 19th century. My sense is that Joseph Smith picked up on it and expressed it in religious terms as exaltation. Ralph Waldo Emerson picked up on it and gave it a more secular expression — as when he argued in Self-Reliance that, instead of being content merely to follow Moses or Jesus or Buddha, we should strive to be Moses or Jesus or Buddha. That is, instead of living more or less passively in the world created by the truly great figures of human history, we should strive to be a great figure and create a new new world for people to live in.

And why is it that we can do such a grandiose thing? Says both Smith and Emerson (but not mainstream Christianity): it's because we are not fundamentally any different than Jesus, etc. Whatever they had, we also have. What they have done, we have the potential to do. (You can perhaps sense the relation of such thinking to the political side of democracy: there's no intrinsic difference between the humble farmer and the snooty aristocrat, etc.)

I could go on, but instead I would encourage you to simply to read Self-Reliance and the the King Follett Discourse side by side and judge for yourself. (Whitman's Leaves of Grass too, where you'll see the same ideas playing out.)

And mainstream Christianity's hostility to Mormon theosis? I'm thinking it might just be rooted in the fact that, by creating a religion that was so much more characteristically American and democratic, Smith pointed up the limitations and un-Americanness of the older creeds.

Pierce,

It may be a logical extension of the doctrine of theosis, but I don't think it is necessarily a logical conclusion, because the doctrine of the plurality of gods creates havoc for the Judeo-Christian concept of God. And it also creates illogical and irrational scenarios. For instance, God, as understood by theologians like St. Aquinas and St. Anselm, is truly the beginning. He is a cosmic force of some sort that is truly eternal and is the true source of all things. But if one posits that God is an exalted man, than you have set up a scenario in which we cannot logically and rationally state who or what the beginning of everything was. It completely defies logic. It establishes the proverbial "chicken or the egg" and forces it upon the concept of God.

You rightfully say that this concept is "limited." That is a nice way of putting it. It is not only limited, it is also completely and utterly illogical. The Christian concept forces us only to deal with the concept of eternity (no beginning and no end), which is difficult to grasp. But at least it presents us with a starting point for everything, a starting point that never itself started. An "unmoved mover."

The difference can be summarized in this way:

Christian God: There was no beginning to God, and God is the beginning of all things.

Mormon God: There WAS a beginning to God, so God cannot be the beginning of all things.

If you are honest with yourself, you know that the Mormon God is not the God described in the Bible. Nor even the Book of Mormon for that matter.

Also, Pierce, think of this:

The Mormon God created the human race through some sort of procreative process with his Heavenly Wife. If it is truly the case that a procreative process requiring the union of two genders is required to produce spiritual children, then it would follow that spirit bears are created through the union of two heavenly bears. And spiritual horses are created through the union of two heavenly horses. And thus, God is not the creator of bears and horses in the same way that he is the creator of human beings. And this leaves wide open the question of who, then, created the bears and horses? God cannot be consider their creator, not in a spiritual sense, and therefore not in a any physical sense either. Something higher up than God had to be the source of all things, including God. And therefore, as I've expressed elsewhere on this site, (you may have missed it) the Mormon God is a lesser deity, and more akin to some of the conceptions of God you'll find in Gnosticism. Which had a significant influence on esoteric and occultic systems, which brings us directly to Joseph Smith.

Christians believe that God created all things. A gendered God cannot be the creator of all things.

Hi everythingbeforeus,

Just as long as you realize that you are jumping to conclusions that are not canonized nor accepted but merely fun speculation then there is no argument. You also have to know that we just don't know what the nature of a resurrected body is and if we were to carry the process of resurrection to its final conclusion, we realize that that the gift of resurrection violates the 2nd law of thermodynamics. I bring up resurrection because it is a gift that a lot of the Christian world believes in but it is not explained how the process happens. In Mormon theology, the resurrected body is part of exaltation and if we can't explain resurrected bodies, then we certainly can't explain what it is like to live in an exalted state let alone how the creative process works.

What am I saying then? We know what is revealed and we don't know what has not been revealed. We can speculate on what has not been revealed but at the end of the day, it is speculation and not doctrine therefore Mormons do not believe in horse gods.

Steve

Orbiting,

It's been a while since I read Self Reliance. I can accept your assessment on the basis that Joseph Smith wasn't really a prophet. However, I believe in a different basis, and I have found a very great harmony between exaltation doctrine and biblical scripture–some examples being ones Jeff quoted in an earlier comment. The comparison you make to Emerson is fine, but I did read it in the Bible first, like Romans 8:16-17. While you can explain Joseph as being a product of the Enlightenment, we can also turn to religious ideas of apostasy and dispensations and go that route. Depends on perspective.

The one point I liked in your assessment of the hostility is the open-endedness of exaltation doctrine. I'm not quite on board with calling it American and democratic–since it really isn't American in origin and has nothing to do with democracy (with the exception that a person can reach their full potential unhindered).

EBU,

What I am about to say is based more on musings and personal experiences rather than dialogue based on formal philosophers.

"But if one posits that God is an exalted man, than you have set up a scenario in which we cannot logically and rationally state who or what the beginning of everything was"

I think a mysterious, all-powerful eternal being that had no beginning and has no end and who creates matter out of nothing makes about as much cosmic sense as the glorified man doctrine, tradition aside. It's funny you call exaltation doctrine illogical because it produces a chicken-egg situation, but try talking with an atheist about your version of an eternal being who creates matter out of nothing and they will tell you that's anything but logical. As far as our worship and understanding goes, we have the same starting point: "In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth…" Anything beyond that is ultimately outside of our ken. To say that we as Mormons are limited in our understanding of the cosmos is true. To imply that we are more limited than mainstream Christianity is untrue. Just because new information adds more questions, it doesn't make it untrue or illogical.

"If you are honest with yourself, you know that the Mormon God is not the God described in the Bible"

For that matter, the New Testament God does not appear to be the same as the Old Testament God either. But Paul and Peter didn't limit their new understanding of God to what Moses understood and taught. Quite frankly, the Bible gives only the smallest snippets of the nature of God the Father. We learned more about His nature through his earth-born Son, Jesus. But even Jesus was mostly quiet about the cosmic stuff. So when mainstream Christianity bristles at doctrine like exaltation, what I think is happening is tradition and culture are being challenged by more information about the nature of God. As a Mormon, I'm ok with that. Heck, it even happens within Mormonism!

I feel there is a reason to believe that exaltation (theosis) has its foundation in the Bible, and Joseph Smith clarified and expanded on it, even if it was limited–which is what a prophet does. Sure, you're not going to find the Mormon version completely spelled out in the Bible, and I am ok with that. I don't really see Paul's salvation doctrine in the OT (or in the Gospels for that matter), but it has a foundation there. I think newer dispensations have always added onto former ones.

I don't follow you on the whole spirit bears thing. Maybe it's the arrogant American in me but I think humans and gods are on a different level than animals. I believe God created the bears and their spirits as stated in Genesis. I don't see how that can't happen because of exaltation doctrine. If you're familiar with this doctrine, you'll know that God took intelligences and created spirits, which he then placed into bodies. It may very well be that he invented bears altogether. Am I missing something?

I have actually read on evangelical sites that only those who profess a belief in Jesus ( only evangelicals) will be on the ground/floor bowing, or prostrate, to Jesus for eternity. Seriously.

So a family unit is offensive to non LDS.

Pierce, and Jeff, may I ask what you think of my original comment about Psalm 82? To repeat what I said at the very beginning of the comments:

Psalm 82 poses a distinct challenge to LDS notions of exaltation. On the one hand, it confirms the existence of other gods. On the other hand, it depicts God as criticizing those other gods for being unjust. But how could other gods possibly be unjust? Wouldn't they have to have advanced way beyond that possibility in order to enter into their exaltation in the first place?

Note that I'm not saying the LDS doctrine of exaltation is wrong, merely that Psalm 82 conflicts with it.

I'll take a crack at it. Could it be that God is classifying us as something like the same species as Him, but chastising us for not living up to the potential that comes with that? Admittedly I am coming at this from a non-scholarly perspective, but that's what I see when I read the psalm, and it seems consistent with my understanding of lds theology

Psalm 82 is rooted in the ancient concept of the divine council, which is consistent with LDS themes. It appears to be speaking to humans who could temporarily be called "gods" due to receipt of divine law and covenants, but who rebelled. This usage of "gods" is different than our usage where we are referring to the divine potential of man in the next life, but certainly does not eliminate the concept of more faithful beings in God's presence being divine–which is more what the divine council concept is about. It (Ps. 82) also appears to differ from the meaning Christ drew from it in John 10, though it may be resolved with Peterson's approach (considering it as directed to premortal humans, in light of God and humans not being unrelated species), or perhaps it really doesn't need to be resolved, as McClellan suggests. In either case, Psalm 82 supports the concept that humans can be called "gods." But it's more complicated and challenging than we have commonly assumed. McClellan's article takes a responsible and well reasoned approach in understanding the challenges and still affirming that as used by Christ, it is associated with the potential divinity of humans. But perhaps not as useful for the LDS position as other passages and the early Christian sources.

Being sons of God is also an important element in Psalm 82, which is consistent with LDS theology. It is the father/child relationship taught in the scriptures that is at the root of the divine potential of humans. If God is wholly other, a completely unrelated species, then that teaching would seem unjustified.

Seems pretty convoluted to me, Jeff. The far more straightforward explanation is that the psalm is rooted in the early polytheism from which Israelite religion struggled to break free — a polytheism in which, as we know, some of the gods were pretty nasty characters. Please fogive me if I see your explanation as decidedly ad hoc and thesis-driven.

But that's the general way with LDS apologetics: "So, you say X conflicts with my theology? Well, here's a convoluted explanation of how X is actually consistent with that theology. It's not an explanation that would be even remotely plausible to a non-LDS scholar, but it's good enough for me, because it affirms what I already know to be true."

St Gregory of Nazianzus said that the purpose of the incarnation was so that he "might become God as (God) became man." But this same man who seems to be preaching exaltation also argued that the "Son" is not a literal biological descriptor, and he mocks those who see "human family ties" in the Godhead. He says that in Greek the Godhead is a feminine noun but we don't therefore assume that the divine nature is a girl. So just because God says "son" can we be justified in assuming that he means biological progeny?

The doctrine of adoption makes more sense (only makes sense) if we first consider ourselves not of the divine family. Then we have something to be adopted into. Otherwise we are only being adopted into the family from which we spring biologically.

It is a good idea when you read the writings of the early church fathers to read it to find what they are saying, not to read it to find Mormonism there.

Hi everythingbeforeus,

I can see how your theology on adoption makes sense. My understanding of adoption from a Mormon perspective is that while we are spirit children of our Heavenly Father, Christ has paid for our sins and as such, Christ has "purchased" us and he becomes our Father after everything is said and done. Thus, we are adopted children of Christ because of his atonement.

Steve

Psalm 82 is not dated to the early days of Judaism. It's later, as McClellan explains. But the concept of a council of the gods subservient to God is a persistent and widespread notion, as is the concept of there being sons of God, which is also obviously present in the New Testament. That is an important element in Psalm 82, a point which also is consistent with LDS theology.

It is the father/child relationship taught in the scriptures that is at the root of the divine potential of humans. If God is wholly other, a completely unrelated species, then that teaching would seem unjustified, and Christ's words in John 10 would not be so powerful a response to the charge against Him.

EverythingBeforeUs, it is through receiving the full blessings of the Atonement that literal spirit sons and daughters become more fully sons and daughters and joint-heirs with Christ. Recall what Paul taught the Greeks: "For in Him we live, and move, and have our being; as also certain of your own poets have said, ‘For we are also His offspring.’" (Acts 17:28). We are made in His image, we are His children and offspring, He is the Father of our Spirits (Hebrews 12:9), and, if we accept Him through His son and take His yoke and covenants upon us, we can mature into true sons and daughters of God, to be like Christ when He comes. That to me helps us make the most sense of Christ's great prayer in John 17.

Steve,

But there is absolutely no Biblical support for that version of adoption. Christ does not become a father-figure. We are joint-heirs with Christ, adopted as sons. Christ is the "only begotten of the Father. He is the real Son. He remains the Son to the Father, and we are adopted in as sons, and therefore heirs, joint-heirs with the real Son.

Good resource on theosis: the work of Father Vajda, exploring Christian theosis and its relationship to LDS doctrine. http://www.thisdiyhouse.com/thomascrowe/Masters/LDS/Partakers%20of%20the%20Divine%20Nature.pdf He later became Brother Vajda.

Vajda's work is available at the Maxwell Institute, but it is hard to read (IMHO) using their quirky layout. You have to find a menu button on the right (3 lines) that gives a drop-down menu to navigate the chapters. Is there a PDF there that I'm missing? http://publications.maxwellinstitute.byu.edu/fullscreen/?pub=2680&index=1&keyword=vajda

Quotes from early Christians about theosis do not imply that they agreed with us on all doctrines. The big changes that led to the metaphysics of the creeds with the influence of Greek philosophy to us represent significant departures from the viewpoints held in earliest Christianity, and there are many things that have been revealed in the Restoration that might not have been known clearly in that day. So there will be differences between our views and those of any given author. But St. Gregory's acceptance of consubstantiality in the Godhead rather than a more literal father/son relationship, if that is a fair of expressing his stance, does not undermine the basic premise that he taught a form of theosis and understood that there is divine potential within human beings. We may differ on how why that is possible and how it is achieved, but he is one of many witnesses showing that theosis was an important aspect in some significant parts of early Christianity.

Jeff, there were lots of "earliest Christianities." Some agree with Mormonism, some do not. The early councils wiped out a lot of doctrines that Mormons would consider heresies also. Why do Mormon apologists not consider these doctrines to be a sign of what the 100% pure Christianity looked like? Why do they take what they believe in now, go back to the ancient times, and then pick and choose through the varieties of early Christianity and piece together scattered ideas and doctrines that look like Mormonism?

Orbiting,

My two cents: it could go either way for Psalm 82. I've taken secular Old Testament courses before and your view is consistent with their explanations of these kinds of verses. It's hard for any Christian to determine inspired vs. cultural passages in the OT (or even the NT), and this one is a good candidate for controversy for someone like me.

Though I will nit-pick with your complaint that something becomes too convoluted if it is not the secular one. You have presented one explanation, but there are other possibilities to explore. Jeff's explanation didn't seem too convoluted to me.

EBU,

It makes sense to look retroactively and pick and choose when you believe in Restoration doctrine. We're not exactly looking into the past and trying to decipher what the 'real deal' was–we believe the 'real deal' was restored already. So we use that as a baseline to determine what ancient beliefs we endorse and which ones we do not. That's the benefit of believing in modern prophets and revelation–it establishes a more legitimate baseline.

What's your baseline that helps you choose which doctrines to adopt and which ones to not?

Jeff, I tried. Orbiting really hates Mormonism.

Orbiting knows a lot about Mormonism and is obviously well read. I just wish he would not give so many personal jabs in his comments. It would make for a more meaningful and positive discussion. Sorry about my pervious comment. 🙂

EBU, same can be said with your brand of heretical Christianity.

Anonymous.

What do you mean by my "brand of heretical Christianity?" What specifically are you referring to?

Pierce,

I will assume that you know that the concept of "restoration" was not unique to Mormonism. It actually predates Mormonism with the Stone-Campbell Movement. Sidney Rigdon was involved in this movement in a heavy way. Restoration was already "in the air" before Joseph Smith put pen to paper.

Two options:

1. God was preparing the people in the vicinity to accept Mormonism when it came around.

2. Mormonism is simply a very successful extension of a larger cultural movement.

Don't see how other restoration movements are material to this discussion. I am interested in what your baseline is tho.

Pierce,

Sorry to have gotten distracted. Baselines.

I think it strange that when I was a missionary, never once was I encouraged to ask my investigators to pray about the role of Jesus Christ as a Savior. Never once. And I was in Japan, where we could never assume that our investigators were beginning with this common faith. Isn't that strange to you, Pierce? I think it is very telling about where the Church's priorities are. We only encouraged our investigators to pray about the Book of Mormon and Joseph Smith. Maybe latter-day Prophets and Restoration, too. I'd have to dig out the old discussion manuals and verify. But I do know that the manuals did not encourage us to ask them to seek a testimony of Jesus Christ through prayer.

When I gave up all psychological attachment to the church and approached God alone for help, then I began having the spiritual experiences I was told were possible. I am a Christian now as a result of that experience. What was pleasantly surprising to me is that when I began receiving spiritual guidance from God, I was taught certain truths. I began to really crack open that Bible, that most neglected and misused book in Mormonism, and what really shocked me is that I found the truths that I was learning clearly spelled out in that book. I had read it before, but always through a Mormon lens. Take off the Mormon lens, and you will see that the Bible is not a Mormon book.

My baseline is the combination of the Word of God with the power of the Holy Spirit, who was promised to teach truth. Spiritual experiences alone are amazing, but we have been warned that we can be deceived through what may feel like a spiritual experience. And why not? Demons are spirits. That is why we need something concrete. I trust that the Bible, despite its "issues, is a trustworthy source of truth. We need to judge all experiences by the doctrines taught therein. If any Gospel is taught that differs from what has been taught, even if an angel above teaches it, we are too reject it as accursed.

So, with all these warnings about evil spirits appearing as beings of light, of false prophets, false apostles, and even false Christs, what is your baseline, Pierce, to determine that Joseph Smith was not deceived? What have you got to rely on apart from your own feelings?

If I understand you correctly and I were to sum it up your baseline for determining which doctrines, philosophies, and positions you accept is your very own interpretation of the Bible. Do you believe you are immune from making errors, being a spiritual island? How do you know that you are not deceived or are not being a false prophet by teaching your own interpretations of a book in which prophets were speaking to the people of their time?

I don't really see how that is any way superior to the methods that God used anciently: using living prophets and apostles–not interpretation of books–as the baseline. I trust Joseph Smith the same way that you or I trust Peter, and for the same reason; the fruit. Or Mathew, Mark, Luke, or John (some of whom weren't even ordained apostles).

You trust God's word and your own feelings. How is that any different than a Mormon testimony? Mormon missionaries even encourage people to read the scriptures, ponder, compare, and pray about it all–and that's all you've said you do. It's a weird sort of Christian rhetoric against Mormonism–don't fall for it.

If I was going to get really into this discussion, I would describe how I believe other types of Christianity are a "different Gospel" then what is taught in the Bible, such as the Evangelist's salvation or the Calvinist's predestination. When I compare those doctrines to what is found in Bible as a whole, I find it completely inconsistent. My point is, the Bible as a baseline is *good*, but it is not definitive and never was. God's pattern has always been and still is to use living leadership. So when a modern prophet comes along and expands on the doctrine of theosis–a doctrine with roots in the Bible–I can adopt it with confidence and enjoy the fruits of further light and knowledge.

EBU,

You say Mormons pick and choose and piece together scattered ideas..

Your religion does the same. All the criticisms lobbed at Mormonism can be turned around and lobbed right back at what you believe to attack your beliefs.

Mormons are heretics according to everyone. There are other religions that say your brand of religion is heretical too. There are other religions, not just Mormons, that say everyone is wrong but them.

Critics who say they are right and Mormons are wrong (the critics who come on Mormon blogs and show what jerks they really are and all the anti Mormon sites run by jerks) are in denial about how their arguments can be turned around and used against them to show how they ( the critics) are wrong. And when it happens (when the tables are turned on the critics) the critics go on a tangent and resort to personal attacks, hateful and condescending remarks and so forth. Which proves the critics do not want true

dialogue and do not really want to understand.

Example: "I began to to really crack open that Bible, the most neglected and misused book in Mormonism. " If someone were to say something like that to you, which they have in past posts, you would and have, pitched a fit and resorted to extreme rudeness and downright nastiness.

Pierce,

When you compare the Evangelist's salvation or Calvinist predestination to what is taught in the Bible as a whole, you find inconsistencies. And therefore, you know to reject Calvinist doctrine by that test. Yet, the fact that the Bible says nothing about eternal families and temple sealings doesn't compel you to reject Smith's teachings?

I know…Smith was restoring truth.

Well, how do you know Luther or Calvin weren't restoring truth that was lost from the Bible? Why are their inconsistencies tossed aside but Smith's embraced and accepted.

I see this kind of stuff, and I have to wonder what exactly Mormons have placed their testimony in. It really seems like the core of their testimony is in Joseph Smith and his organization. Christ is an afterthought.

And I have to say that from my experience in the Mormon church for 38 years and my few months attending various Protestant denominations has been most illuminating. The Lutherans, the Methodists, the Congregationalists, the Episcopalians….none of them spend their Sunday worship talking about themselves. At all. No one stands up and declares how great it is to be a part of this church. Now words of reverence spoken about Luther or Calvin or any other reformer or living leader. No Sunday service spent talking about Girl's Camp or Boy Scouts or Youth Conference. No one talks about that glorious day of Reformation.

From the start to the finish of the Sunday service, it is entirely directed toward Christ, his Atonement, his Resurrection, and our resulting salvation. They speak about Christ, not about their church. This isn't the way it is in Mormonism.

Wow. Looks like you're here to grind your axe at this point, using up space to go from one complaint to the other, with testimony meetings being the latest casualty. There's a lot to say about your latest criticism, but I can't keep following you down your little tangents.

Hi everingbeforeus,

You do bring up too many points so I will choose which point to counter. The missionary discussions that I used (1990) I remember specifically that the first discussion was about God and the Son and asking the investigators if they believe in God and in His Son, Jesus Christ. I could not find my discussion booklets to confirm this. If the investigator did not believe, there was always a challenge to gain a testimony so I do believe you are remembering incorrectly about your missionary discussions.

By the way, I really don't believe you when you said that you have psychologically removed yourself from the Church just for the fact that you visit sites like mormanity and deposit your criticisms of the Church.

Steve

Steve,

Find your discussion booklet. I used the same ones you did. Yes…the first discussion taught about God and Christ, but at the end, the commitment the investigators were asked to make was to read and pray about the truthfulness of the Book of Mormon. At no point were missionaries directed to ask them to pray about Jesus Christ.

I never said I psychologically removed myself from the church. I said I went before God in prayer with no psychological attachment to the organization. There is a difference.

Pierce,

Sorry if I am all over the board. My college students also have to deal with my distracted habits when I lecture about art history. To me, everything is connected. Are there a few points you really want me to address? I'll try to stay on topic.

Anonymous,

You talk about my religion. Can you please tell me what my religion is? I've never declared loyalty to any religion on this blog.

But since you are talking in these terms, there is agreement between Catholics, Presbyterians, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Adventists, Methodists, Congregationalists, and other Protestants about the doctrine of the nature of God. The vast majority of the world's Christians accept the same creeds, those written statements of belief. Now, you may disagree with the creeds. That is perfectly your right. But the state of disarray that Mormons like to claim exists within the Christian world is a myth.

There are a few groups who do not accept these creeds. If you look into the other beliefs of these fringe groups, I don't think Mormons would want to be lumped into this company. Mormons make a hard effort to be seen as mainstream Christian. But Mormons have doctrines that are not mainstream.

Hi everingbeforeus,

One too many moves, can't find my discussion booklets at the moment but here is a list of the titles:

1. The Plan of Our Heavenly Father

2. The Gospel of Jesus Christ

3. The Restoration

4. Eternal Progression

5. Living a Christlike Life

6. Membership in the Kingdom

If I were to guess based off of the titles, the first two lessons focus heavily on God and Jesus Christ and the prophets. Each section had challenges for the investigator such as knowing if Jesus was the Son of God and died for our sins. My discussions will turn up eventually. I served my mission in Italy so we rarely encountered someone who did not believe in Jesus. We did run into an atheist who was really curious how he could know about God. We told him that he would need to read the scriptures and start praying in order to have a relationship with Heavenly Father. Maybe it didn't occur to you on your mission that you needed to encourage people who did not believe in Jesus to read the scriptures and pray so that they can come to a knowledge about the Son.

Your words "When I gave up all psychological attachment to the church…" I still think that you are attached to the Church. How could you not be? You gave it your all for a portion of your life. It is hard to cut ties so easily.

Here is a list of Christian creeds in the non-disarrayed Christian world:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Christian_creeds

Cheers,

Steve

Steve, I am saving you time. I've already checked. The discussions never encouraged the investigators to pray to find out if Jesus is the Savior, the Son of God. The discussions teach Jesus, but it was not suggested that the investigators pray about it.

If you read the Wikipedia page you suggested, you'll see that all the primary creeds listed are accepted by nearly all Christian denominations. Which is what I was saying. There is agreement on the basic doctrines of the Godhead.

Mormonism accepts no creeds at all, but will excommunicate you if you preach false doctrine.

Hi everingbeforeus,

I stand corrected.

Cheers,

Steve

Pierce makes an excellent point in his use of the word "speculating" as does an Anonymous. When it comes to the eternities before and after us, we know almost nothing. In both science and religion, the origins of the cosmos are remote and mysterious. Because the few slivers of revelation we have coupled with our best speculations leave loose ends that do not fit into our preconceived notions and modern philosophies, it is tempting to see that as a sufficient reason to reject what we believe has been revealed. For those with faith, a smarter approach may be to recognize that we don't yet understand and be patient. The traditional views of Hellenizrd Christianity may sound neater at first glance, but do not redolve the problems. What is God? How does He exist? How did He create the cosmos out of nothing? If immaterial and wholly other, How does he create and control matter? How can we be in his physical image, for that is the plain meaning of those words? If he resurrected with a tangible immortal body, where is it now? And on and on.

We still cannot explain much about this earth beneath our feet. To expect attempts at explaining the origins of everything to make good sense to us now is a lost cause. But we know God is the Creator and we are his offspring. All of us, as Paul must have meant. But we become most fully sons of God when we, His spirit children, become adopted through His covenants of grace to be more like His only begotten son, the God who obviously once was and still is Man.