If you aren’t following the journal Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship, you may have missed some discoveries and advances in understanding our scriptures that could be helpful for your own spiritual and intellectual journey. I will disclose my bias as a co-editor of the journal, where I have the privilege in this volunteer role of working with some remarkable authors as their articles go through our peer review process. It’s great to work with the many bright people who submit articles to the Interpreter Foundation for consideration in the journal. It has been a delight to learn of their insights and discoveries as they dig deep into many aspects of our faith and our scriptures. Here are just a few of many recent highlights.

“An Ishmael Buried Near Nahom” by Neal Rappleye

Background

One of the most intriguing Book of Mormon evidences from the Arabian Peninsula involves the episode during Lehi’s journey in which Ishmael dies and was then buried in a place that was called Nahom, as described in 1 Nephi 16:34. The discovery of three altars bearing the NHM name, apparently related to Yemen’s Nihm tribe near that region was active, indicates that a name related to Nahom was prominent in Lehi’s era, providing hard evidence from the right time and roughly the right place in favor of the plausibility of an unusual place name in the Book of Mormon. Much has been written about that and also discussed here, with a plausible candidate for the place Nahom being in the region of Wadi Jawf, not far from Sanaa. From Wadi Jawf, it is possible to make the abrupt turn in direction from generally south-southeast to nearly due east, as Nephi describes, and travel without having to cross the deadly Empty Quarter or to face impossible mountains or other impassable obstacles to reach at least one and apparently both of the leading candidates for Bountiful in southern Oman. See, for example, Warren Aston, “Across Arabia with Lehi and Sariah: ‘Truth Shall Spring out of the Earth,’” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 15/2 (2006): 8–25, 110–13; https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1401&context=jbms. Also see Warren P. Aston and Michaela K. Aston, In the Footsteps of Lehi (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Comp., 1994); Warren P. Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia: The Old World Setting of the Book of Mormon (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris Publishing, 2015); and George Potter and Richard Wellington, Lehi in the Wilderness: 81 New, Documented Evidences that the Book of Mormon is a True History (Springville, UT: Cedar Fort, Inc., 2003). For videos, see Lehi in Arabia, DVD, directed by Chad Aston (Brisbane, Australia: Aston Productions, 2015), available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PgDNCG-7×98, and Journey of Faith, DVD, directed by Peter Johnson (Provo, UT: Neal A. Maxwell Institute of Religious Scholarship, 2006), available at https://journeyoffaithfilms.com/videos/watch-journey-of-faith.

The New Publication

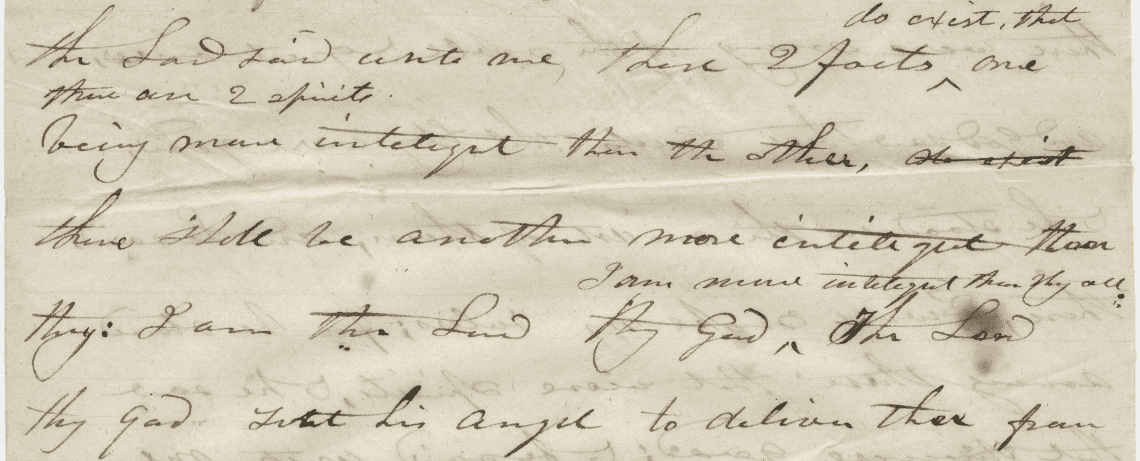

Thanks to Neal Rappleye, we now have what may be another find of interest, one of 400 carved funerary stelae from Wadi Jawf. With detailed scholarship and a good deal of caution, Neal Rappleye explores the possible significance of an ancient inscription from Yemen indicating that someone named Ishmael (equivalent to the carved y s1mʿʾl in Epigraphic South Arabian) was buried, possibly in the region of the candidate for Nahom, in what may have been Lehi’s day. We don’t know if it was the same Ishmael of the Book of Mormon, of course, but as Rappleye gently suggests, “circumstantial evidence suggests that such is a possibility worth considering.” However, there are questions about the provenance (not the authenticity) of the stela since it was part of a group of looted items that were recovered, so the exact site where it was found is not known, though it seems we can say that it was made for an Ishmael “buried somewhere within or near the Wadi Jawf, ca. 6th century BC.” It is possible that it was associated with the ancient lands of the Nihm tribe, as is the case for other items in the collection. The dating of the stela and nature of the name are also compatible with the Book of Mormon account:

The stela is paleographically dated to 6th–5th centuries BC, but Mounir Arbach and his co-authors consider it stylistically among “a few coarse examples” of the incised face elements stela type “known for the 7th–6th centuries BC.”

The name Yasmaʿʾīl is the South Arabian form of the name Ishmael, even though the two names may look somewhat different in translation. The inscribed y s1mʿʾl is exactly how the Hebrew name yšmʿʾl (ישמעאל) — typically rendered as “Ishmael” in English — would be spelled in Epigraphic South Arabian. In fact, the two names have the exact same etymology, meaning “God has heard/hearkened,” or “may God hear,” and in The Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon of the Old Testament, the Old South Arabian y s1mʿʾl is listed as an equivalent to the Hebrew name yšmʿʾl (Ishmael). Thus, this stela indicates that a man named the equivalent of Ishmael was buried in or near the Wadi Jawf around the 6th century BC, about the same time period Ishmael was buried at Nahom, according to the Book of Mormon (1 Nephi 16:34).

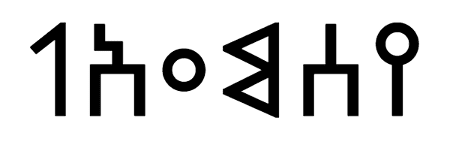

|

| The name “Ishmael” (Yasmaʿʾil) in Old South Arabian script. |

Rappleye also explains why the name most likely has Hebrew rather than Arabic origins.

Scholars examining the collection of stelae propose that they were made either for foreigners from the north passing through the area or for the members of the lower ranks of society. In either case, this could fit the case of Lehi’s family, traveling as nomads without the gold and silver Lehi once had in Jerusalem.

Rappleye’s conclusion is intriguing but also appropriately cautious:

At the very least, it seems reasonable to suggest that if the Ishmael of the Book of Mormon was buried with some sort of identifying marker, it probably would [Page 39]have looked something like the Yasmaʿʾil stela — a crudely carved stela typical of foreigners traveling through the area, who lacked substantial time or resources to afford a more extravagantly carved and engraved burial stone.

Although a firmer conclusion eludes us, the very fact that an Ishmael was buried in close proximity to the Nihm tribal region around the very time the Book of Mormon indicates that a man named Ishmael was buried at Nahom is rather remarkable. Such a fact certainly does not weaken the case for the Book of Mormon’s historicity.

Please don’t think or say that “scholars have found the grave marker of Ishmael in the Book of Mormon at Nahom.” But what that they have found, and what scholars have concluded about the collection of Wadi Jawf funerary stelae in general, at least modestly demonstrates the plausibility of the Book of Mormon claim that a Hebrew man named Ishmael was buried at a place called Nahom near Wadi Jawf. Wadi Jawf, as Warren Aston has reported (see his books In the Footsteps of Lehi and more recently Lehi and Sariah in Arabia), appears to be just about the only region where one can turn nearly due east from the main trails leading south through Yemen and not only have a chance of surviving, but, with a little guidance from the Liahona to chose the right final wadi, be on a path that could lead directly to a plausible candidate for Bountiful such as a Khor Kharfot at Wadi Sayq (or nearby Khor Rori, another leading candidate that some prefer).

Don’t make too much of Rappleye’s fascinating find, but it does merit attention and is one more interesting work of genuine scholarship advancing our appreciation of the plausibility of Lehi’s Trail in the Book of Mormon. Rappleye’s careful work helps strengthen the general case for Nahom as one of the “four pillars” of Lehi’s Trail, as Warren Aston put it, places in Nephi’s account with strong candidates for specific Book of Mormon locations in Arabia that were completely unknown in Joseph Smith’s day. These include: 1) the River of Laman in the Valley of Lemuel, 2) the place called Nahom, 3) Bountiful, and most recently identified, 4) the place Shazer, as Warren Aston reported in 2020 in another must-read publication at Interpreter.

“The People of Canaan: A New Reading of Moses 7” by Adam Stokes

Given the mission and scope of Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship, it is natural that our authors tend to be members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This paper was a welcome exception from a man who has great interest in and respect for the Book of Moses, even though his own church does not accept it as scripture. Stokes was formerly with the Community of Christ, but is now a member of the Church of Jesus Christ with the Elijah Message, an organization that traces its roots to David Whitmer. Taking on the sensitive issue of race in the Book of Moses, Stokes brings out some clear and important points that we often miss when reading passages in Moses 7 that seem to reflect old racial stereotypes. What made this article especially interesting to me is that its author is black, though I didn’t know that until after the paper had been accepted and I received the photo now published at the end of the article and also on our “About the Author” page for Adam Stokes.

Here is the abstract for this important article:

Moses 7 is one of the most famous passages in all of Restoration scripture. It is also one of the most problematic in regard to its description of the people of Canaan as black (v. 8) and as a people who were not preached to by the patriarch Enoch (v. 12). Later there is also a mention of “the seed of Cain,” who also are said to be black (v. 22). This article examines the history of interpretation of Moses 7 and proposes an alternative understanding based on a close reading of the text. In contrast to traditional views, it argues that the reason for Enoch’s not preaching to the people of Canaan stems not from any sins the people had committed or from divine disfavor but from the racial prejudice of the other sons of Adam, the “residue of the people” (vv. 20, 22) who ironically are the only ones mentioned as “cursed” in the text (v. 20). In looking at the implications of this passage for the present-day Restoration, this article notes parallels between Enoch’s hesitancy and various attitudes toward black priesthood ordination throughout the Restoration traditions, including the Community of Christ where the same type of hesitancy existed. This article argues that, rather than being indicative of divine disfavor toward persons of African descent, this tendency is a response to the racist attitudes of particular eras, whether the period of the Old Testament patriarchs or the post-bellum American South. Nevertheless, God can be seen as working through and within particular contexts and cultures to spread the gospel to all of Adam’s children irrespective of race.

There are four main arguments made in this paper:

- Moses 7 both reflects and challenges the prevailing understanding of race and ethnic prejudice in the ancient [Page 163]world (yes, concepts of race and prejudice, though vastly different than ours, did exist in antiquity).

- The “people of Canaan” of Moses 7 are never mentioned as being cursed in the text. Rather their blackness is the result of God cursing something else (i.e., the land).

- The only people mentioned as cursed in Moses 7 are the “residue of the people” (vv. 20, 22, 28) which, as the text itself notes, does not include the “seed of Cain” (7:20, 22). In contrast to the prevailing reading of Moses 7, the text implies condemnation not of the seed of Cain/people of Canaan but of this “residue of the people” due to both their hatred of the people of Canaan and their general rejection of the gospel message preached by Enoch.

- Enoch’s rationale for not preaching repentance to the people of Canaan in Moses 7 is not due to any personal animosity toward them or from the view that they are cursed. In other words, his rationale, as the text explains, is different from common interpretations and readings in the Latter-day Saint tradition.

Stokes’s reading of Moses 7 leads to a surprising conclusion that may be controversial but needs to be considered in light of the detailed analysis Stokes provides: “Moses 7, far from being a racially problematic text, presents a progressive racial message in which God himself condemns the prejudice and cruelty of the other sons of Adam. It is this cruelty, in conjunction with their rejection of the gospel, that results in the ‘residue of the people’ being cursed, a curse from which the people of Canaan themselves are spared.” There’s much to ponder in the work from this intriguing author, and I hope you’ll read it carefully.

“The Inclusive, Anti-Discrimination Message of the Book of Mormon” by David M. Belnap

This is one of the most extensive and data-heavy articles ever published by Interpreter. It took a lot of work to go through a lengthy review and editorial process that began and was essentially finished before I came onboard in mid-2020, but I’m very proud of what David Belnap has accomplished and of Allen Wyatt as the lone editor then for guiding it through the process. To get a feel for the significance of this paper, I’ll quote what Adam Stokes said about it in his paper discussed immediately above:

I find it necessary to provide a point of comparison here between my reading of Moses 7 and David Belnap’s excellent analysis of the depiction of the Lamanites in the Book of Mormon. In his recent article for Interpreter, “The Inclusive, Anti-Discrimination Message of the Book of Mormon,” Belnap takes a radically different approach to the sacred text focusing not on the presentation of the Nephites in the Book of Mormon — the standard default position for Book of Mormon exegetes — but that of the Lamanites.

Belnap persuasively and effectively argues that while the negative statements about the Lamanites in the Book of Mormon have been highlighted both by the book’s advocates and opponents, the text ultimately and primarily presents them in a highly positive light. As such, the Book of Mormon ultimately promotes a radical egalitarian and anti-racist ethic which elevates the “dark,” blackened Lamanites over and above their “pure” and “white” Nephite counterparts [note that Belnap and others provide plausible reasons for recognizing the troubling language in the Book of Mormon about the “blackness” or darkness of the Lamanites as metaphorical, not descriptions of racial differences, though there are other possibilities]. He notes that in the majority of instances that the Lamanites are mentioned in the Book of Mormon it is either as equal or better than the Nephites and that in many cases the Lamanites are presented as spiritually superior to the Nephites.

Belnap provides a massive amount of data to show that the Book of Mormon overwhelming denies the racist message that some see in the Book of Mormon:

Counter to the racist impression, more than three thousand Book of Mormon verses directly or indirectly impart an inclusive, anti-discriminatory message (Table 1). People today may perceive the cursing [of the Lamanites] as a racist declaration or a license to discriminate, but righteous Book of Mormon people did not. Wicked behavior of the cursed group was excused, but that of the non-cursed, recordkeeping group was severely criticized. Several times the cursed people were righteous examples or were more righteous than the non-cursed people. People of the two nations were considered brethren. Love of all was preached and practiced. Kind acts occurred between nations and within each nation, including outreach to the other nation and help to the poor within a nation, and some selfless people lost their lives or put their lives at risk. Although often at war, the two nations had significant peaceful interactions. Unkind actions and attitudes toward other groups were identified as evil, including exploitations, class distinctions, persecutions, and attitudes of superiority. War was tragic and caused by wickedness. Intermingled in these messages are messages especially relevant for today. God loves and invites all people. God is fair to all. Prophecies extend his blessings worldwide to modern Jews, other Israelites, descendants of Book of Mormon people, and all other people (Gentiles). The promised blessings will be fulfilled if people choose to follow the Lord. Those who fight against the Lord will incur his wrath, regardless of ethnicity or heritage. Anti-Semitism is condemned. Conspiracies are extremely wicked. The book contains a powerful example of redemption from discriminatory attitudes.

After discussing numerous issues related to alleged racism in the Book of Mormon and its message of inclusion, Belnap writes:

Instead of highlighting how a few verses were interpreted as reflecting 1800s attitudes, a better focus is on the inclusive messages that are in more than half of the book’s verses:

- God loves all people and his message is for all people on earth (Table 4).

- God will treat all people fairly (Table 4).

- God favors personal righteousness, not lineage (Table 4).

- Every group (Nephites, Lamanites, Jaredites, Jews, and Gentiles) has had times of righteousness and times of wickedness.

- All groups need to repent (tables 5–6, 20–22).

- The aim is spiritual beauty and cleanliness, not physical attractiveness (Table 3).

- The Gentiles have persecuted Lehite descendants and Jews. The Gentiles’ need to repent is particularly emphasized (tables 21–22).

- All people (Lehites, Jews, and Gentiles) are promised blessings and happiness if they follow the Lord (tables 4, 17–19).

- Anti-Semitism is evil (Table 21).

- Slavery is evil (Mosiah 2:13; Alma 27:9).

- Righteous Nephites viewed the Lamanites as brothers, and vice versa (tables 11, 13).

- Righteous Nephites reached out to the Lamanites, and vice versa (Table 12).

- Righteous people were kind to others. Sometimes these acts cost unselfish people their lives or put their lives at risk (Table 13).

- Unkind actions against others are condemned (Table 14).

- Persecution or oppression of others is wickedness (Table 15).

- Attitudes of superiority are condemned (Table 15).

- Class distinctions are evil (Table 15).

- Exploitation of vulnerable people is evil (Table 16).

- Although defensive war may be necessary, war is started by wickedness (Table 23).

- Conspiracies, which in our day are involved in some discriminatory actions or crimes, are extremely evil (Table 24).

- The wicked punish the wicked (Mormon 4:5).

- On no occasion do righteous Nephites seek to destroy Lamanites or vice versa (Table 23).

- People can learn from despised people. Multiple times Lamanites, who were scorned periodically by the Nephites, are examples of righteousness (Table 8), even when “unconverted” (Table 9).

- Christ taught us to focus on fixing ourselves and not others (3 Nephi 14:3–5; Matthew 7:3–5). The Nephite record does that by focusing on Nephite faults and de-emphasizing Lamanite ones (tables 5–7, 9–10).

Righteous people in the Book of Mormon cared about others. Whatever the differences truly were between the Nephites and Lamanites, those people gave us much to learn from in our day of unrelenting discrimination.

As Belnap ably shows, the Book of Mormon as a whole has a consistent message that is needed in our day. The few passages that cause concern need to be considered in light of Belnap’s work and the scholarship he discusses (e.g., works of Ethan Sproat and Brant Gardner) on interpreting those verses, but stay tuned for more coming soon on another important insight from modern scholarship that may advance our understanding of some challenging Book of Mormon passages in light of ancient culture in the Americas. An article that I’m looking forward to will be published soon, so stay tuned.

“Personal Relative Pronoun Usage in the Book of Mormon: An Important Authorship Diagnostic” by Stanford Carmack

Stanford Carmack and Royal Skousen have published a series of works exploring the language of the Book of Mormon as originally dictated. One of the most puzzling discoveries, driven by data and not any apologetic agenda, is that much of what we assumed was Joseph’s own bad grammar actually turns out to be legitimate Early Modern English, with many elements that predate the English of the King James Bible. What that means is that the details of the English in the Book of Mormon, as dictated, cannot be simply explained as Joseph imitating what he found in the Bible. And in many cases, it doesn’t seem possible to explain it as an artifact of Joseph’s own language or New England dialect in his day. Why it should be this way is still a mystery, but it’s an important issue worthy of recognition, and one that may raise the bar for those arguing that Joseph Smith is the fabricator of the Book of Mormon.

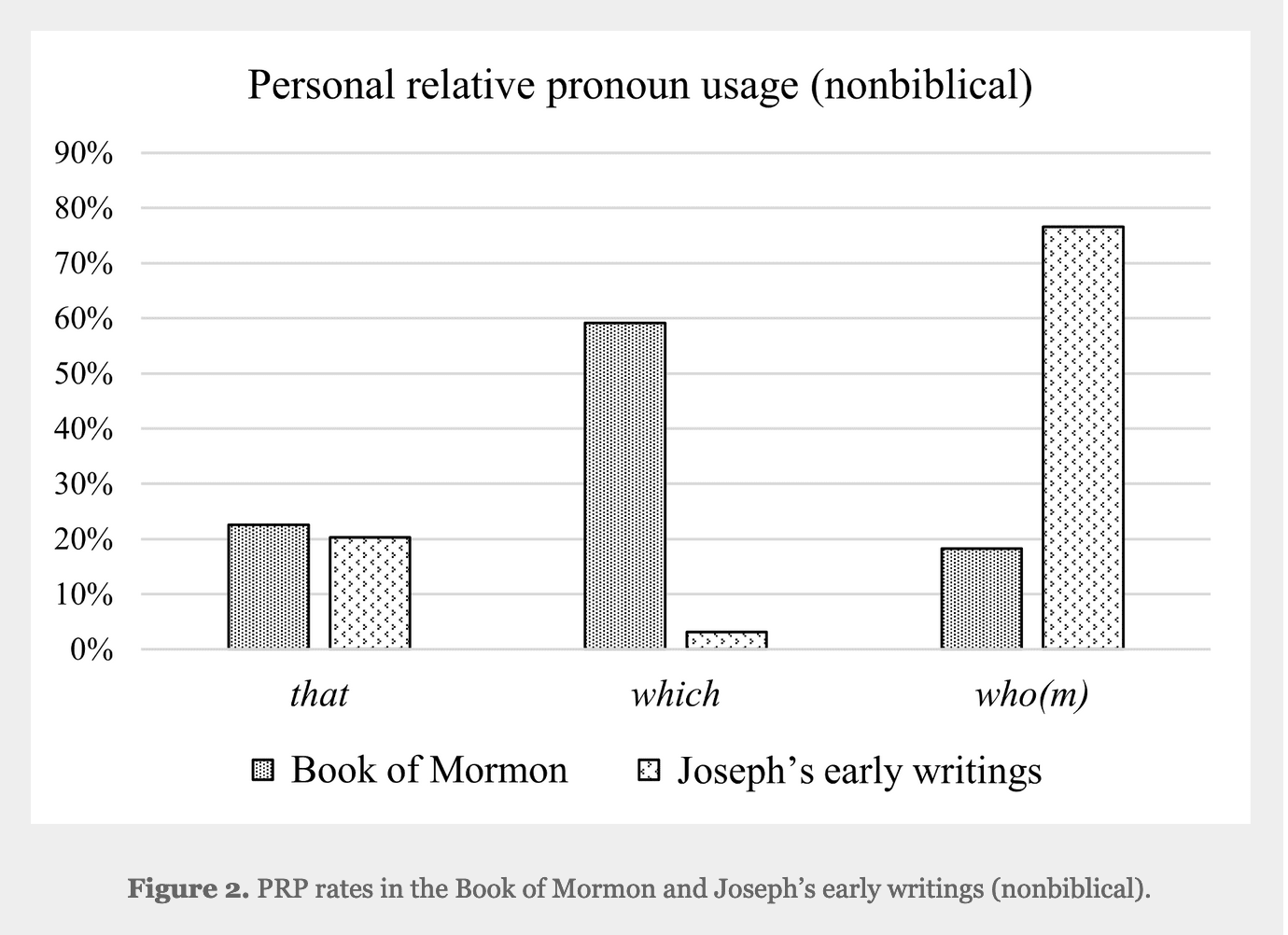

Some of Carmack’s many works on this topic, including quite a few at Interpreter, explore complex or highly technical topics and may be difficult for many of us appreciate, but this one deals with an issue that most of us can easily grasp, even if we aren’t familiar with some of the terminology. Carmack explores the use or “personal relative pronouns” in the Book of Mormon and other works. Personal relative pronouns (PRPs) are pronouns that relate one clause to another. As an example, consider the sentence, “The author that wrote the paper was a fine scholar.” After mentioning the author, we can then refer to the author again in a new clause with a PRP such as “that” or “who.” There is also third possibility that is less commonly used in modern English, the PRP “which,” which was more frequently used in the Early Modern English era (roughly 1470 to 1700). But all three choices (“that,” “who”/”whom”/”whose,” and “which”) need to be considered as Carmack compares the Book of Mormon to Joseph’s early writings, the KJV Bible, other “pseudo-biblical” literature that deliberately sought to imitate the KJV Bible, and Early Modern English literature.

Carmack first considers how Joseph himself used PRPs in his early writings (10 letters and his 1832 personal history). The data here should be easy to grasp (click to enlarge): Joseph predominantly used “who(m)” but also had a modest share of “that” in his language, with “which” being rather rare as a PRP. The Book of Mormon reverses the “who”/”that” balance, strongly preferring the use of “which” as a PRP, quite unlike Joseph. The choice of PRP is something we don’t tend to think about consciously, just saying what feels natural at the time. Such unconscious choices of minor words can be something that is hard to notice and hard to fake when seeking to imitate a style.

Carmack then compares the Book of Mormon to the Bible, where large differences again emerge. The KJV Bible uses the PRP “that” 86% of the time, followed by “which” 10% of the time and “who(m)” just 4% of the time.

Considering the antecedent for PRPs can add additional information related to the syntax of a text. Based on analysis of some major databases, Carmack observed that PRPs most frequently occur after the words “he” and “they,” and also noted that the PRPs used with them may differ. After “they,” the PRP of choice in the Book of Mormon is “which,” occurring 69% of the time, while after “he” it is “that” 90% of the time. The “he” + PRP pattern in the Book of Mormon is quite similar to the Bible’s, while “that” + PRP are sharply different, with the Bible preferring “he that” 79% of the time vs. 68% “he which” in the Book of Mormon. But the choices for “he” and “they” + PRP in the Book of Mormon closely matched several Early Modern English texts, while not matching pseudo-biblical texts.

Carmack’s conclusion has startling implications:

The statistical argument for each scenario outlined above is compelling — whether we look at all PRP usage, a subset involving high-frequency antecedents, or just contexts involving the subject pronouns he and they. We can tell with exceptionally high confidence that the Book of Mormon’s PRP patterns were not derived from Joseph Smith’s own patterns, from the King James Bible, or from attempting to imitate biblical and/or archaic style. We can also tell that the patterns do match a less-common pattern that prevailed during the middle portion of the early modern period, but not in the 18th century — a pattern with an overall preference of personal which over that or who(m).

In the case involving more antecedents than just he and they, a simple examination of the dramatic differences shown here or an application of standard chi-square tests of the raw numbers (see the appendix) indicate that the Book of Mormon’s PRP pattern would not have been achieved by closely following the patterns of the King James Bible, pseudo-archaic works, or Joseph’s own dialectal profile, which at times was biblically influenced. The large differences in PRP usage between the Book of Mormon and the King James Bible and pseudo-archaic works indicate a different authorial preference for these sets of texts — a preference that is mostly nonconscious, as shown by an inability of pseudo-archaic authors to sustain archaic/biblical usage over long stretches. The Book of Mormon is not a match with the usage in Joseph’s personal writings, as his own patterns fit comfortably in the late modern period, as do most contemporary pseudo-archaic works.

This point has been made in other contexts, including various iterations of stylometric analysis, but the force of the data is difficult to deny, even though it is based on only a single linguistic feature. (These PRP comparisons are in effect a kind of focused, precise stylometry.) Furthermore, the data lead us clearly away from Joseph as author or English-language translator and toward a specific time period — the only time when we find textual matching with the Book of Mormon’s archaic PRP distribution rates: the early modern era, and primarily the second half of the 1500s and the first decade of the 1600s.

This is puzzling. Why it should be that way is a mystery, and Carmack states he does not wish to speculate, but points out that the important thing is that the data weigh strongly against the common assumption that the Book of Mormon simply reflects Joseph’s own wording. We know Joseph edited portions of the text, sometimes taking out the awkward grammar he had dictated to make it more clear or proper, so he was not averse to using his own language when he felt it was needed. But if Carmack is correct, it seems that what he dictated cannot be assumed to simply be his own wording.

This is a controversial position, but one that seems based on a growing body of detailed data. There are other popular views on the nature of the translation and the influence of his own wording, and I look forward to the replies of other scholars in exploring alternate theories. The debate, if focused on the data, will be fascinating.

No publication should ever be assumed to be the final, definitive word. There’s always more to learn and new data to consider. Our goal at Interpreter is to advance scholarship and faith by publishing what we hope are meaningful, solid works related to the scriptures, Church history, and other gospel topics for others to consider and, in many cases, respond to with new advances. Whether an article offers the ultimate answer or just some great questions and issues for further thought, we hope they will be helpful to readers and will remind all of us of the need to keep learning and growing in our faith and study.

I’ll share some more thoughts from recent publications in another upcoming post or two. If you have a favorite recent publication, let me know what you liked and why in the comments below.

I'll never understand why some people see racism in the Book of Mormon.

@gaelicvigil therefore we can safely assume 2 things:

a) you're white

b) you've never truly read it critically, only from a position of faith

Seems like another valuable and logical comparison would be to other “inspired” texts Joseph created by means of dictation, namely documents from the Pearl of Great Price. I’m wondering why Carmack hasn’t included those documents in his comparisons? They shouldn’t be included in the baseline database, only as a like-to-like comparison of his other works.

A quick search of the PoGP shows 50 usages of the word which, and 32 who’s. Here’s an example of a verse from Joseph Smith History where both are used in the manner Cormack describes:

10 In the midst of this war of words and tumult of opinions, I often said to myself: What is to be done? Who of all these parties are right; or, are they all wrong together? If any one of them be right, which is it, and how shall I know it?

I do not think that the "residue of the people" in verse 20 is alluding to a group of people apart from whatever others that were living at the time.

The phrase is used again in verse 28 when "the God of heaven looked upon the residue of the people, and he wept." This would seem to indicate that was referring to the all of the people on the earth.

Most people, including me, probably think of residue as a relatively small quantity, the definition, as we have it today, "something that remains after a part is removed, disposed of, or used; remainder; rest; remnant." (Dictionary.com) It appears that God was speaking of a very large group of people, the ones that were not of the city of Zion.

That usage is again apparent in verse 43 when "the residue of the wicked" is all of the people that were not on Noah's ark.

Glenn

Carmack did compare the Book of Mormon's personal relative pronoun usage with Joseph Smith's early writings, including the 1832 history, as well as early Doctrine and Covenants revelations. See the body of the paper for the former and the appendix for the latter.

And those aren't relative pronouns in Joseph Smith's history. They're interrogative pronouns. The antecedent is one of several religious groups, which can be referred to by either who or which, so those don't tell us anything. Actually, his 1832 history doesn't have personal which at all, something that Carmack already addressed in an earlier paper.

I agree, Nephites viewed Lamanites as "brethren." They were of the same race, so there couldn't really be racism.

In addition, there's a lot of evidence that the skin references were symbolic, cultural, ancient, etc.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for your site. You have some really great posts and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d absolutely love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an email if interested. Thank you 먹튀사이트 I couldn't think of this, but it's amazing! I wrote several posts similar to this one, but please come and see!!