|

| The cover of the Hebrew edition of Meir Bar-Ilan’s The Words of Gad the Seer |

An old Jewish manuscript said to contain writings of Gad the Seer, one of the “lost books” mentioned in the Bible was found among Jews in India and after much drama has recently been published in English. It’s an intriguing story that I think should be given more attention, especially among Latter-day Saints.

Gad was a prophet living at the time of David who seemed to have special status based on 2 Samuel 24:11, which speaks of “Gad, David’s seer.” But like many prophets, Gad was not afraid to speak unpleasant things to his King (e.g., see 2 Samuel 12:1-13). One of the very few mentions of Gad occurs in 1 Chronicles 29:29 when it mentions that the acts of David the king were written “in the book of Gad the seer.” I have occasionally cited that verse in discussing the scriptures with others who accept the Bible to illustrate that the Bible we have might not contain all the scripture that has been written in the past. A common rejoinder is, “There may have been such a book, but if God didn’t preserve it for us in the Bible, it’s not scripture.” I guess there can be no such thing as lost scripture with that definition. And if it can’t be lost, I guess it can’t be found. In reply, I have asked others what they would do if a book that ancient Jews or Christians regarded and preserved as Biblical scripture became lost, and then was found again?

Surprisingly, my theoretical question became a little less theoretical with the fairly recent discovery, translation, and publication of a long-lost manuscript that may have connections to the ancient lost book of Gad the Seer, just published in 2016. The document has been through many human hands and may have some of the corruption common to non-canonical works such as the Apocrypha and pseudepigrapha, but the scholar who has explored this text in the most detail and provided the translation believes it has ancient roots and is worthy of our attention. The story of this unusual text may be relevant to our own and much more miraculous story of the finding, translation, and publication of the ancient books of scripture from ancient Hebrews and Christians that we have in the Book of Mormon.

The Story Behind the Words of Gad the Seer

The story of coming forth of The Words of Gad the Seer is a story that involves the the scattering of Israel and a Jewish colony in India, and may raise interesting issues about ancient Jews not only in India but also in Yemen with possible relevance to Lehi’s Trail. This story also touches upon themes of lost and restored ancient scripture, apocalyptic literature like the Book of Enoch and our own Book of Moses, writing on metal plates, and other Latter-day Saint themes such as free agency, three main categories of outcomes in final judgment, and even Alma’s discourse on the word as a seed in Alma 32.

There may be much food for thought as we contemplate the story behind the text and the words themselves now published in a very short book, The Words of Gad the Seer translated by Professor Meir Bar-Ilan (Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Publishing, 2016), available in paperback and Kindle editions. His much more extensive scholarly edition is available only in Hebrew at the moment. Professor Bar-Ilan has been a professor for decades at a prestigious university in Israel, Bar-Ilan University, named for another Meir Bar-Ilan (perhaps his grandfather?), a prominent figure in Israeli history. Bar-Ilan University is often abbreviated as BIU, not to be confused with BYU. At BUI, Bar-Ilan teaches in both the Talmud and Jewish History departments and has an interesting list of publications, a number of which are related to the Words of Gad the Seer.

Before you rush to buy Meir Bar-Ilan’s English translation of the Words of Gad the Seer, you should know that what is currently available is a bare-bones paperback just 23 pages in length giving the 5000+ words of the pseudepigraphal text without any explanation, background, footnotes, etc. With the Kindle edition, you can’t even figure out who published it. The Barnes and Noble page for the book indicates that the publisher is CreateSpace Publishing, something I could not find at Amazon, and a search then revealed Scotts Valley, CA as the likely location for the publisher. Wikipedia’s entry for “The Book of Gad the Seer” indicates that one there is a scholarly edition in Hebrew that I presume will be more complete. But you can access a variety of articles in English that Professor Meir Bar-Ilan has written about the book that I’ll discuss below. Meanwhile, I hope you will still buy the book, perhaps the Kindle edition, and begin exploring this unusual text.

Slightly more information and a slightly different translation is available in Christian Israel’s independently published 2020 version, The Words of Gad the Seer: Bible Cross-Reference Edition, available in paperback only (no Kindle edition so far).

The largest English volume available as far as I know, with both Kindle and paperback editions, is Ken Johnson’s Ancient Book of Gad the Seer: Referenced in 1 Chronicles 29:29 and alluded to in 1 Corinthians 12:12 and Galatians 4:26 (Ken Johnson, 2016). This has extensive and questionable commentary from Ken Johnson, who appears to be an evangelical seeking to strongly guide the reader toward his preferred readings, stressing Messianic themes [some of which may be valid] and other favorite topics. For example, he sees the condemnation of Edom as a condemnation of Rome, even inserting “[Rome]” after Edom and stating in brackets that the fall of a “terrible nation” refers to the destruction of Byzantine. The insertion of altered text in brackets that push his pet themes is annoying. Fortunately, Johnson has provided his translation without all the commentary and with fewer bracketed insertions in a free PDF that one can read online or download.

The translation I trust the most is that of the Jewish scholar, Professor Bar-Ilan in The Words of Gad the Seer. Any quotes from the book of Gad the Seer will be from his translation, unless otherwise indicated.

What follows is an overview of the book taken from Barnes and Noble (also provided at Amazon) which I believe is just a translation from the Hebrew describing Bar-Ilan’s 2015 scholarly edition, which I hope will soon be available in English. I say that because this overview describes a book with an index, a vast bibliography, a description of its origins, comparisons to others texts, and scholarly analysis of literary genre, scribalism and scribal techniques, none of which is in the English translation, but much of which should be fascinating for Latter-day Saint scholars.

Gad is a prophet most associated with King David in the Holy Bible. This book is the outcome of a prolonged study of a manuscript that was found serendipitously 34 years ago. Actually, this was a re-discovery of a text that for some reason had escaped the eyes of many. It is a story of the survival of Jews remote in place and time, and of their books, visions, angels and divine voices, combined with their belief in God and his covenant with King David and Israel. There is no other book that resembles this one.

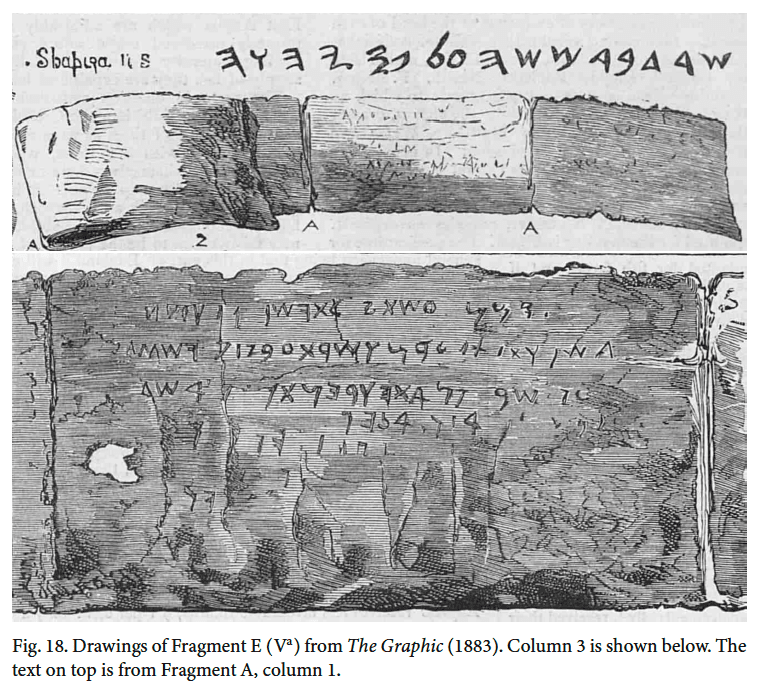

A book by the name Words of Gad the Seer is mentioned at the end of I Chronicles, presumably one of the sources of the history of King David. Ever since the book was considered lost and it is mentioned nowhere. In the 18th century Jews from Cochin said that their ancestors have had several apocryphal books, including Words of Gad the Seer, and this statement was published first by Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1789) and translated by Naphtali H. Wesseley who publicized these fantastic claims (1790). Since none saw the book, it was probably considered to be an oriental legend. So when Solomon Schechter, in 1894 (just before he became occupied with the Genizah), checked manuscripts at the Cambridge library, bought at Cochin around 1806, [he] not only … described the specific manuscript improperly but he also failed to make the right connection to earlier knowledge of that book and thus he under-evaluated the text. In 1927 Israel Abrahams published a paper on this manuscript, but his analysis, once again, had several improper descriptions, and hence the text of Words of Gad the Seer went into oblivion.

This book presents the text of Words of Gad the Seer for the first time. First comes an introduction where the history of the manuscript is discussed. Later the characters of the text described and analyzed one feature after the other. The text is found to be having many similarities with the Book of Revelation and several pseudo-apocryphal and apocalyptic books such as 2 Baruch, 4 Ezra and others.

Then comes a diplomatic edition of the manuscript where each and every letter (by special fonts) is presented similarly to the manuscript. Later the book is divided to 14 chapters, each is a literary unit by itself, and each has its own introduction and a commentary. Each and every verse is explained in a “multi-focal” commentary in a manner similar to publishing a Biblical book: literary criticism, lexicography, philology and alike. A special treatment is given to the scribal practices that are reflected in the text: the only non-canonical book with a Massorah, Qeri and Ketib, total number of verses and more.

The book is 5227 words in length written in a pseudo-Biblical Hebrew intended to be a book written by the Seer of King David in the 10th century B.C.E. The text is an anthology and varies in style and character: 3 chapters are apocalyptic in nature, 2 chapters are a “mere” copy of Ps 145 and 144 (with different superscriptions and all sorts of different readings, some of them highly important); one chapter is a harmonization of 1 Sam 24 with 1 Chr 21 (that resembles ancient harmonizations of texts as found in the Samaritan Pentateuch and Qumran alike). One chapter is a kind of addendum to 2 Sam 13 (a “feminine story”), one chapter is a sermon, one chapter is a folk story, and there are more blessings, liturgies and other issues. Literary genre, scribalism and scribes’ technique are described and analyzed. The book comes with an index and a vast bibliography. The appearance of the text will add a great deal to our understanding of Jewish History and religion.

Date: The text assumed to be written either in the Land of Israel at the end of the first century or in the Middle Ages

More information on the background is provided by Ken Johnson on pp. 8-9 of his book:

The History of the Book German Protestant theologian Johann Gottfried Eichhorn was born in Ingelfingen, Germany, on October 16, 1752. He was the professor of Oriental languages at Jena University from 1775 to 1788. While there, he authored several books including, Introduction to the Study of the Old Testament, and Introduction to the Study of the Old Testament – Scholar’s Choice Edition. While studying the Aramaic New Testament, he came across a legend called the Chronicle of the Jews in Cochin. A chronicle is the earliest history of how a people got to a remote region. Chronicles frequently begin with the world-wide flood and traces one of Noah’s sons down to the founder of that particular country. According to the Cochin chronicle, Shalmaneser, King of Assyria conquered Samaria in the ninth year of Hoshea. This event is also recorded in the Bible:

“In the twelfth year of Ahaz king of Judah began Hoshea the son of Elah to reign in Samaria over Israel nine years. And he did that which was evil in the sight of the LORD, but not as the kings of Israel that were before him. Against him came up Shalmaneser king of Assyria; and Hoshea became his servant, and gave him presents.” 2 Kings 17:1-3

The Codex Judaica states in the Hebrew Year 3195 AM, Shalmaneser exiled the tribes of Zebulun and Naphtali. The chronicle describes how during Shalmaneser’s attack and resettlement of the nation, four hundred sixty of these Jews escaped and went to Yemen under the leadership of Rabbi Simon. They took with them their holy books (the Old Testament) and, in addition, they preserved the books of the prophets Gad, Nathan, Shemaiah, and Ahijah. Several hundred years later they were again exiled. They knew of Jewish settlements living in relative peace in Poona and Gujarat, India, so they left Yemen and migrated to India. About seven hundred years later, forced conversions began. A group of less than three hundred Jews moved to the Malabar region in India, where they were welcomed and protected. Most stayed in the port city of Cochin (also called Kochi). A Jew named Leopold Immanuel Jacob Van Dort translated the Hebrew text from the Patriarch of the Jews in Cochin into Dutch in 1757. It was later translated into German and sent to Eichhorn. He published that copy in 1786. Naphtali Herz Wessely republished the Hebrew version. In the nineteenth century, another copy reportedly emerged from Rome and is now housed in the Cambridge Library in England. The University of Bar-Ilan in Tel Aviv, Israel, has published the Hebrew text, and in 2015, Professor Meir Bar Ilan of Bar Ilan University published a Hebrew version of the text with commentary (it also includes an English translation).

There is a Gnostic version by the same name; but any real book that the Lord has seen fit to preserve would, of course, have a Satanic counterfeit with the same name. Anything Gnostic or Kabbalistic had to be a false work or, at least be heavily edited by the cults of that time.

The translation of Gad the Seer in this book is a modern English translation with commentary based on Scripture from a conservative Christian perspective. [emphasis mine]

A similar account with more detail is provided by Prof. Meir Bar-Ilan in “The Discovery of The Words of Gad The Seer,” Journal for the Study of Pseudepigrapha 11 (1993): 95-107 (footnotes omitted):

Some two centuries ago, a very puzzling testimony was published in Germany; no one could tell what in it was true and what was false. One of the founders of modern Biblical scholarship, J. G. Eichhorn, published an unusual document he had received indirectly from the Jews of the remote community in Cochin, India. This publication struck the imagination of many people, and it was soon translated into Hebrew by one of the eminent scholars of the time, Naphtali Herz Wessely. Wessely not only translated the material, but wrote a commentary on it, trying to evaluate some of the unusual statements in that document. In his article in one of the first academic Hebrew journals, HaMeasef, he began by discussing the geographical discoveries that led to a new concept of the world, facts that might help to find the lost Ten Tribes. His discussion was some kind of ‘foreword’ to the main evidence he took from Eichhorn in order to discuss the history of the Jews in Cochin.

According to Wessely, the source of the testimony was a man by the name of Marcellus Bless, a clerk in the Dutch East India Company. This man got his information from a converted Jew, Leopold Immanuel Jacob Van Dort. In 1757 Van Dort copied extracts from a Hebrew book that belonged to the Patriarch of the Jews in Cochin. Van Dort found this so interesting that he translated it into Dutch and gave it to the above-mentioned clerk in Ceylon. Some thirty years elapsed before the evidence was brought to the attention of a man by the name of Ruetz who translated the extracts in Dutch to German and sent them to be published in Eichhorn’s Bibliothek. Strange as it sounds, these people did exist and quite a bit is known about some of them.

Thus, this chain of languages – Hebrew, Dutch, German, Hebrew (and now, English) – is unusual, and is part of the unusual evidence the testimony bears. At any event, the Jews in Cochin relate their history and wanderings in a unique story, of which only a few lines interest us. According to that ‘Chronicle of the Jews in Cochin’, their special history began in the exile caused by Shalmaneser, King of Assyria, who conquered Samaria in the ninth year of Hoshea the son of Elah (2 Kgs 17:1 ff.). Shalmaneser exiled 460 Jews to Yemen, and the chronicle says:

These exiled people brought with them (to Yemen) a book of Moses’ Torah, book of Joshua, book of Ruth, book of Judges, first and second books of Samuel, books of: 1 Kings, Song of Songs of Solomon, Songs of Hallel – David, Assaf, Heiman and the sons of Korah, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes of Solomon, as well as his Riddles, prophecies of Gad, Nathan, Shemaiah and Ahijah, age-old Job, Jonah, and a book of Isaiah, etc.

These books were preserved under the authority of the patriarch of the Jews, ‘Shimon Rabban from the tribe of Ephrime, who was the first (patriarch) in the period of Yemen captivity who attempted to preserve the books’. The Chronicle of the Jews of Cochin continues with a description of the history of those books which, according to it, were confiscated by the king, and only after a fast and prayers were the books returned to the Jews – 10 years later. For our purposes it should be added that some 500 years later the Jews in Yemen were exiled by King Prozom.

Since the exiled people had known of the Jews in Poona and Gujarat in India, they preferred to go there, and they and their descendants lived there for some 600 or 700 years. Almost all of those Jews were forced to convert, and less than 72 families moved from Poona and Gujerat to Malabar. Those who moved were welcomed by the governor, Cherman Perumal, who gave them privileges to encourage them to stay there, as is written on copper plates, and there in Cochin, the copper plates have remained until this day, in the days of the patriarch of the Jews Joseph Hallegua. Bless mentioned that this Joseph was a brother-in-law of Ezekiel Rahabi (who will be mentioned later). We can determine that this ‘Chronicle of the Jews of Cochin’ is from the first half of the 18th century.

Bar-Ilan notes that the Jews of Cochin had other documents as well such as the writings of Nathan, Shemaiah and Ahijah, texts that are mentioned in the Bible, as well as the Riddles of Solomon which is not mentioned in the Bible. There may be much more to mine from the treasures related to the Jews of Cochin.

Connections to Explore

There is much more to the story as Bar-Ilan explores the various efforts to publish information about the Words of Gad the Seer. In spite of all that he describes, it’s amazing how poorly known this text is. Bar-Ilan in “The Discovery of the Words of Gad The Seer” offers a reason why this has occurred:

This intriguing story of the lost books at Cochin is near its end. It is hardly credible that books that were mentioned in three languages, and especially in so many Hebrew editions were later overlooked. The only possible reason for that, I assume, is that the fascinating stories emerging from Cochin were considered to be legendary in character, such as any modern scholar should ignore. When one of [these] ‘legends’ became true [discovery of the manuscript for The Words of Gad the Seer], its source was already forgotten and the whole issue was misunderstood and misjudged. However, in future studies I hope to demonstrate the significance of The Words of Gad the Seer, its date, its geographical source, and much more.

As we see in the accounts of the background story, the Words of Gad the Seer may have roots in scriptures brought by ancient Jews who fled to Yemen. Perhaps this happened near the time when the Ten Tribes were scattered, with some from the Ten Tribes seeking new homelands. Ancient Jewish colonies in Yemen are an important aspect of the diaspora (see “Jews of Yemen – History – When did Jews Settle in Yemen?” at Wysinfo.com, and “Yemenite Jews” at Wikipedia). As I discuss in my Interpreter article, “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dream Map: Part 1 of 2,” Warren Aston has suggested that a Jewish colony in the area of Nahom/Nehem in Yemen may have assisted in providing a proper Hebrew burial for Ishmael. Jewish burials in Yemen are attested no later than 300 BC, and since we know of later Jewish presence in the Nihm area, it is possible that Jews could have been there earlier and could have been able to assist in proper burials. See Warren Aston, Lehi and Sariah in Arabia, Kindle edition, Part 3, sections “Ishmael’s Death,” “Nahom Today,” and “Where the Jews Once Part of the Tribe.” See also Part 1, section “Religion in Arabia,” where Aston notes Yemeni Jewish traditions of seven ancient Jewish migrations into Yemen. Further, there is evidence that Jewish traders and merchants were interacting with Yemen before Lehi’s era. It would be fascinating to know what versions of a book from Gad the Seer might have been brought to Yemen anciently, perhaps both by Jews who established colonies in Yemen and by Lehi on his brass plates.

One aspect of the story of ancient texts among the Jews at Cochin, India is the issue of writing on metal plates. The Jews at Cochin were said to have kept their ancient history on copper or brass plates, consistent with traditions of using copper plates in India for important legal documents going back at least to the 3rd century BC. A hint about scriptures written on metal comes from one source who visited the Cochin colony several times early in the 1700s, Captain Alexander Hamilton (a British sailor, not the US statesman). He stated that they had kept their history recorded on copper plates stored in a synagogue. This statement is found in A New Account of the East Indies, vol. 1 (London: 1744), 323–24, available at Archive.org (https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.278509/page/n375/mode/2up) and Google Books (https://www.google.com/books/edition/A_New_Account_of_the_East_Indies/-jNagGDT-PsC??hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA323&printsec=frontcover). He reports:

They [the Jews in Cochin, India] have a Synagogue at Cochin, not far from the King’s Palace, about two Miles from the City, in which are carefully kept their Records, engraven in Copper-plates in Hebrew characters; and when any of the Characters decay, they are new cut, so that they can shew their own History, from the Reign of Nebuchadnezzar to the present Time….

They declare themselves to be of the Tribe of Manasseh…

I have previously discussed Hamilton’s statement here on my blog at https://www.arisefromthedust.com/2020/12/the-jewish-copper-plates-of-cochin.html (previously known as Mormanity).

Many decades after Hamilton’s various visits to Cochin, Claudius Buchanan visited the Jews there and reported on them in his 1811 volume, Christian Researches in Asia, but he makes no mention of their records on plates stored in a synagogue. Buchanan does describe ancient “tablets of brass” created by a Syrian Christian group in Malabar, India, which were deposited in the Fort of Cochin and “on which were engraved rights of nobility, and other privileges granted by a Prince of a former age” (pp. 112-3). While these long thought to be lost, they were found and put in possession of a British officer, Lieutenant Colonel Macaulay, who gave the following description:

The Christian Tablets are six in number. They are composed of a mixed metal. The engraving on the largest plate is thirteen inches long, by about four broad. They are closely written, four of them on both sides of the plate, making in all eleven pages. (Buchanan, p. 113).

He also quotes from the journal of Lord William Bentinek, who was Governor of Madras and visited Cochin from 1806 to 1808:

On my inquiry into the antiquity of the White Jews, they first delivered to me a narrative, in the Hebrew Language, of their arrival in India, which has been handed down to them from their fathers; and then exhibited their ancient brass Plate, containing their charter and freedom of residence, given by a king of Malabar. (Buchanan, pp. 171-2)

Bentinek does not describe the medium of the Hebrew record, but it presumably was not on metal plates or he would have mentioned that. The ancient brass plate mentioned is the royal charter granted to the Jews of Cochin by a king of Kerala, India, a record engraved on copper plates (see “Jewish copper plates of Cochin,” Wikipedia). The set of three plates associated with the charter have a traditional date of 379 A.D. but are more likely to date to around 1000 A.D.

But Claudius Buchanan did far more than merely mention the brass plate of the Cochin Jews. He had a replica made and transported to Cambridge, but there is controversy about whether he actually kept the original and gave the replica back to the Jews at Cochin. In fact, the original owners of the royal charter may have been left with nothing. It’s a messy story in need of scientific testing of the plates, as discussed by Thoufeek Zakriya of India in his blog post, “The Copper Plate and the Big Sahib,” Jews of Malabar, Aug. 19, 2013, http://jewsofmalabar.blogspot.com/2013/08/the-copper-plate-and-big-sahib.html. It’s a powerful reminder of how important it is to keep precious writing on metal plates out of sight and out of the hands of others. Hurray for burying plates in stone boxes!

Did the Jews at Cochin really have more ancient records of their history on copper or brass plates, or did the story of their one small document become inflated when it was told to Hamilton? He gives enough detail that it doesn’t seem possible he got confused about a story involving one or two plates, but was he given correct information? Did the Jews at Cochin have much more that they did not risk discussing with Buchanan? Are there records on plates still in hiding somewhere? I have no idea, but would be thrilled if such a thing did exist and could be brought to light. For now, we just have Hamilton’s report and the tradition of writing on copper plates in India that might add to the plausibility of the story. The document from the Cochin Jews bearing the Words of Gad the Seer was not written on metal plates.

Update, 4/4/2022: A reader with the moniker “RM Zosimus” posted a comment here pointing to what may be the earliest published mention of the copper plates of the Cochin Jews:

As far as I can tell, the first western account of metal plates among the Jewish and Christian communities of Cochin comes from Damião de Góis in his “Three Letters of Mar Jacob”. Mar Jacob, the Bishop of the Thomas Christians between 1543 and 1545 mentioned two copper plates with inscriptions in Pahlavi, Cushic (sic) and Hebrew script. These plates are unrelated to the chronicles of the Cochin Jews that were said to have been destroyed when the Portuguese burned down the synagogue in 1662 AD. This history was inexplicably called the sefer ha yashar or the Book of the Upright One or the Book of Jasher.

The “Three Letters of Mar Jacob” are not easily found online, but were discussed by Georg Schurhammer in The Malabar Church and Rome during the early Portuguese period and before (Trichinopoly [the British India name for Tiruchirappalli city in Tamil Nadu], India: F.M. Ponnuswamy 1934), pp. 14 and 22-23 (esp. footnote 69) available at https://archive.org/details/malabarchurchrom00schu_0/page/22/mode/2up. The “Three Letters of Mar Jacob” are reproduced in Portuguese early in the volume with an English translation at the side, and the mention of a copper plate in the second Portuguese letter has “do que temos hua [dua?] lamyna [lamina] de cobre asselada de sseu sselo,” with the given translation “of which we have a Copperplate sealed with his seal” (p. 14). On pages 22-23 is mention of several plates, some now lost. Fascinating!

A few more connections to explore will arise when we examine some passages from the text below.

Assessing the Words of Gad the Seer

So what of this strange document from Cochin, India, the Words of Gad the Seer? Is it just pious fiction made up by some Jews in India? A 1927 article argued that it was likely written in the 13th century AD. See I. Abrahams, “The Words of Gad the Seer” in Livre d’hommage a la mémoire du Dr Samuel Poznański (1864-1921) (Vienna: Adolphe Holzhauzen, 1927), pp, 8-12. On the other hand, Professor Bar-Ilan in “The Date of The Words of Gad the Seer,” Journal of Biblical Literature 109, no. 3 (1990): 477-493, has examined the text in detail and argues that it has more ancient roots. He estimates its origins to be in the first centuries of the Christian era.

Could it be earlier? Bar-Ilan says no, for the book is written as an apocalypse, and biblical scholars generally maintain that such literature, including First Enoch, the book of Daniel, and the book of Revelation, is a literary genre generally limited to roughly 200 B.C. to 200 AD., characterized by similarity to the book of Revelation, with secret divine revelation about the end of the world and the nature of heaven. See John J. Collins, “Introduction: Towards the Morphology of a Genre,” ed. John Joseph Collins, Semeia 14 (1979): 1, though Collins notes a later example of Jewish apocalyptic literature, the Sefer Hekalot (3 Enoch), which some have dated to the 5th century AD. Being apocalyptic, the argument is that Words of Gad the Seer cannot represent biblical literature from the time of David or otherwise much before 200 BC. (Some of us Latter-day Saints, however, may be open to more ancient origins for some apocalyptic literature like the material on Enoch in our own Book of Moses.)

Bar-Ilan in the above-cited Journal of Biblical Literature article (also available at Academia.edu) considers the arguments made for a medieval origin and refutes them in detail, and then argues the case for late antiquity. His first argument will be of interest to Book of Mormon students:

The Words of Gad the Seer incorporate three chapters from the Bible as if they were part of the whole work. Chapter 10 here is Psalm 145, chapter 11 is no other than Psalm 144, and chapter 7 is a kind of compilation of 2 Sam 24:1-21 with 1 Chr 21:1-30, a chapter that deals with the deeds of Gad the Seer. As will be demonstrated later, the Biblical text in Gad’s book is slightly different from the masoretic text, with some ‘minor’ changes that might be regarded as scribal errata, though others are extremely important. In any case, this phenomenon of inserting whole chapters from the Bible into one’s treatise is known only from the Bible itself. For example, David’s song in 2 Sam 22:2-51 appears as well in Psalm 18:2-50, not to speak, of course, of other parallels in Biblical literature.26 It does not matter where the ‘original’ position of this chapter was. Only one who lived in the ‘days of the Bible’, or thought so of himself, could have made such a plagiarism including a Biblical text in his own work. [emphasis mine]

Now that’s fascinating. This is not some unschooled Latter-day Saint apologist desperately trying to argue that heavy biblical plagiarism is not a reason to reject the antiquity of an allegedly ancient document like the Book of Mormon. It is a prominent scholar of Hebrew literature writing in a respected peer-reviewed journal on biblical literature stating that the extensive “plagiarism” of biblical material in a work is a characteristic of ancient literature that helps rule out a relatively modern origin for the text. The things Nephi and other Book of Mormon writers do with other biblical texts, widely condemned as blatant plagiarism by our critics, might actually be indicators of antiquity, not modernity.

His second argument is also of interest, pointing out that the way Bible content is merged and reworked in the document is also uncharacteristic of modern writings but is an indicator of antiquity. That is also a characteristic of Nephi’s writings in the Book of Mormon as he combined various passages and reworks them in elegant ways, something Matthew Bowen and others have discussed, See, for example, Matthew Bowen, “Onomastic Wordplay on Joseph and Benjamin and Gezera Shawa in the Book of Mormon,” Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship 18 (2016): 255-273.

His third argument involves differences in the way the Psalms are quoted, particularly the changes in superscriptions that seem authentic. But another interesting and possibly authentic twist is the addition of the missing “nun” verse in Psalm 145, a Psalm where each verse begins with a letter from the Hebrew alphabet forming an acrostic, with an apparent defect due to the absence of the letter “nun” that should be between verses 13 and 14 (see the missing verse discussion in “Psalm 145,” Wikipedia). The added verse reads “All your enemies fell down, O Lord, and all of their might was swallowed up.” Bar-Ilan feels that “the style and content of the verse give good reason to believe that it is authentic.” But even if it were made up by a creative editor, he says “it still would be interesting, since the sages of the Talmud did not know it, and the invention of fictitious Biblical verses is not known in the Middle Ages either.” The added verse combines the falling of enemies and swallowing up, a combination also seen in the Book of Mormon in 2 Nephi 26:5, where Nephi speaks of the coming destruction of those that kill the prophets, warning that the depths of the earth “shall swallow them up” and “buildings shall fall upon them.” Likely a random parallel, but possibly interesting, coming from one of the Book of Mormon writers most attuned to the Psalms (see my “Too Little or Too Much Like the Bible? A Novel Critique of the Book of Mormon Involving David and the Psalms” in Interpreter).

His fourth argument also sounds somewhat like a common defense of the Book of Mormon as he summarizes the diverse literary styles and tools in the text, and highly creative visions and stories that seem unlikely to have been fabricated.

There are nine arguments in total for antiquity, followed by reviewing two recent cases where a text was deemed by experts to be relatively recent, only to have later discoveries such as a related document from Qumran proving that the document was ancient after all.

Perhaps there will be something to learn as we explore relationships between The Words of Gad the Seer with other overlooked or denigrated texts from the Restoration, namely, the Book of Mormon, the Book of Moses, and the Book of Abraham. For now, let’s consider an overview of the text and look at just a few interesting passages.

Overview of the Content, and a Few Passages of Interest

We turn again to Professor Bar-Ilan for an excellent summary of the chapters of The Words of Gad the Seer, quoting from his “The Date of The Words of Gad the Seer,” Journal of Biblical Literature 109, no. 3 (1990): 477-493:

The Words of Gad the Seer contains 14 chapters dealing with King David and his prophet Gad. The nature of each of the chapters is different than the others, so one who has already read the first chapter, for example, cannot predict any other chapter in the book. The style is Biblical, in accordance with its heroes (some of whom are not mentioned in the Bible or elsewhere). Even when the author writes his own ideas, almost every word or phrase reflects biblical verse. Now, let us consider each of the chapters, one by one.

1. (verses 1-63) God’s revelation to Gad the Seer. The Seer sees animals, the sun and the moon, and all that happens is interpreted by the voice of God. The lamb is sacrificed on the heavenly altar but not before he praises the Lord. Gad is told to tell David his revelation, and David blesses the Lord and congratulates Gad for the secret that God has told him.

2. (verses 64-92) A second revelation to Gad concerning the Last Days. There is a prophecy of devastation on Edom that ‘dwells in the land of Kittim’ while quoting their anti-Jewish opinions. There will be a battle between Michael, the High Prince, and Samael, Prince of the World.

3. (verses 93-104) On Passover a Moabite shepherd asks King David to convert him. David does not know what to do, and he asks the Lord. Nathan the prophet answers in the name of God: ‘Moabite male, not Moabite female’. [This means that the prohibition against Moabites joining the religious assemblies of Israel in Deuteronomy 23:3 applies to males, not females.] The Moabite stays among David’s shepherds and his daughter Sefira becomes a concubine to Solomon.

4. (verses 105-120) A story that praises the nature of King David, the wise judge.

5. (verses 121-130) Before a battle between the Philistines and Israel, the Lord speaks to Gad to tell David not to be frightened. That night a fiery vehicle descends from heaven and smites the Philistines.

6. (verses 131-141) God sends Gad to tell David not to boast of his strength. David admits that all of his strength comes from God. God is satisfied with David’s answer and for that reason He decides that He will help the House of David forever.

7. (verses 142-177) David counts the children of Israel. This is a recension which combines 2 Sam 24:1-25 with 1 Chr 21:1-30. Both Biblical known texts, together with some ‘additions’, appear to be integral chapter in the book.

8. (verses 178-198) God reveals himself to David, telling him he should speak to his people. David gathers the people and preaches to them concerning the Lord’s names and titles. David urges his people not only to listen to the Torah but to fulfill it as well.

9. (verses 199-226) Hiram, King of Tyre, asks David to send him messengers to teach him Torah. David answers that Hiram ought to fear the Lord and to fulfill the commandments of the children of Noah. A list of God’s attributes is given, and the children of Israel are described as sealed with Shaddai. Hiram and his servants believe in Israel’s election and praise Israel. God hears Hiram and sends Gad to tell David that Hiram and his people will prepare His house.

10. (verses 227-249) A praise to the Lord. This is Psa 145 with a different superscription than in the Masoretic text and it includes the missing Nun verse (different from any known version).

11. (verses 250-265) A praise to the Lord. This is Psa 144 with a different superscription than in the Masoretic text (and other minor differences).

12. (verses 266-285) Before David dies he urges his people to adhere to God that it will be good for them forever.

13. (verses 286-353) Except for the first four verses that belong to the former chapter (King David is dead and Solomon becomes King), it is a long story where Tamar, King David’s daughter, plays the role of a heroine. This is a kind of addition to 2 Sam 13. After Tamar was raped, she ran to Geshur and later on one of the King’s servants tried to rape her. Tamar kills her attacker and she comes back to Jerusalem, praised and blessed by King Solomon.

14. (verses 354-375) A revelation. Gad sees the Lord on His throne judging His people on the first day of the year. An angel brings forward three books in which everyone’s deeds are written. The Satan wants to prosecute Israel, but he is silenced by one of the angels. The revelation contains all kinds of details and the Seer does not understand all of them. The revelation and the book end with a blessing by the Seer while an angel answers: ‘Amen, Amen’.

There’s remarkable diversity in the contents of this brief document. It is a document rich in visions and the ministry of angels, similar to themes in the Book of Mormon. Angels or messengers of God are often said to be dressed in linen, the material of sacred priestly robes.

Here are a few passages that struck me as interesting from a Latter-day Saint perspective, just for your consideration. The titles are mine, suggesting themes that occur to me. The passages are given with their verse numbers.

On Purity

16 And it came to pass when the voice of the lamb was over, and, lo, a man dressed in linen came with three branches of vine and twelve palms in his hand. 17 And he took the lamb from the hand of the Sun and put the crown on its head, and the vine-branches and palms on his heart. 18 And the man, dressed in linen, cried like a ram’s horn, saying: ‘What hast thou here, impurity, and who hast thou here, impurity, that thou hast hewed thee a place in purity, and in my covenant 19 that I have set with the vine-branches and palms’. 20 And I have heard the lamb’s shepherd saying: ‘There is a place for the pure, not for the impure, with me, for I am a holy God, and I do not want the impure, only the pure. 21 Though both are creations of my hands, and my eyes are equally open on both. 22 But there is an advantage to the abundance of purity over the abundance of impurity just like the advantage of a man over a shadow.

Israel, the Firstborn People

46 And I heard a voice crying from heaven, saying: 47 ‘You are My son, you are My firstborn, you are My first-fruit. 48 Have I not brought you from over Shihor to be my daily delight? 49 But you have thrown my presents away and dressed up the impure with pure, and that is why all these things happened to you. 50 And who is like unto Thee, among all creatures on earth? For in your shadow lived all these and by thy wounds they were healed! 51 For that consider well that which is before thee. 52 And because you have fulfilled the words of the shepherd all the days you have been in the Sun and you did not leave them, therefore all this honor shall occur to you’. 53 And I, Gad son of Ahimelech of the Jabez family of the tribe of Judah son of Israel, was amazed by the scene and could not control my spirit.

The Seal of Truth

54 And the one dressed in linen came down to me and touched me, saying: ‘Write these words and seal with the seal of truth for “I am that I am” is My name, and with My name thou shalt bless all the house of Israel for they are a true seed. 55 Thou shalt go, for yet a little while, before thou art gathered quietly to thy fathers, and at the end of days thou shalt see with thy own eyes all these, not as a vision but in fact. 56 For in those days they shall not be called Jacob but Israel for in their remnant no iniquity is found for they belong entirely to the Lord.

David Standing on a Pulpit to Speak to His Assembled People

182 Then David assembled all Israel in Jerusalem, and he made to himself a pulpit of wood and he stood upon it before all the people. And he opened his mouth and said: 183 ‘Hear, O Israel, your God and my God is one, the only One and unique, there is no one like His individuality, hidden from all, He was and is and will be, He fills His place but His place doesn’t fill Him, He sees but is not seen, He tells and knows futures, for He is God without end and there is no end to His end, Omnipotence, God of truth, whole worlds are full of His glory.

David Teaches the Concept of Free Agency

184 And He gave each one free choice: if one wants to do good – he will be helped, and if one wants to do evil – a path will be opened for him. 185 For that we will worship our God our king our Lord our saviour with love and awe, for your wisdom is the fear of the Lord and your cleverness is to depart from evil. 186 Remember and obey the law of Moses, man of God, that it may be well with thee all the days.

Comparing the Law to a Seed and Faith to a Tree

187 Ask thy fathers and they will declare unto thee; thine elders, and they will tell thee. 188 Be strong and valiant to obey the law and not to hear it only. 189 For a deed is like a root, hearing it is like a seed, a belief is like a tree and the fruit is like righteousness. 190 And what shall we do to a smelly and stinky seed if a root will not come out of it? 191 For that, hurry up! be quick and act, hear and act, for you are true seed, for you have belief and righteousness then the Lord will bless you all in peace.

On Love for Others

192 Talk peacefully each with one another, and love the deed and those created in the image of the Lord like your own souls. 193 For if you love [man] the created, it is a sign that you love the Creator. 194 And also, thou shouldest take hold of the one; yea , also from the other withdraw not thy hand; love the Lord and also man that it shall be well with thee all the days’.

Three Outcomes on the Day of Judgement

360 And, lo, a man dressed in linen brought before the glory of the Lord three books that were written about every man. 361 And he read in the first one and it was found to have the just deeds of His people, and the Lord said: ‘These will live forever’. 362 And Satan said: ‘Who are these guilty people?’ And the man dressed in linen cried to Satan like a ram’s horn, saying: ‘Keep silent, for this day is holy to our master’. 363 And he read in th second book, and it was found to have inadvertent sins of His people, and the Lord said: ‘Put aside this book but save it, until one third of the month elapses, to see what they will do’. 364 And he read in the third book, and it was found to have malicious deeds of His people. 365 And the Lord said to Satan: ‘These are your share, take them to do with them as seemeth good to thee’. 366 And Satan took those which acted maliciously and he went with them to a waste land to destroy them there. 367 And the man dressed in linen cried like a ram’s horn, saying: 368 ‘Happy is the people that know the joyful shout; that walk, O Lord, in the light of Thy countenance’.

Conclusions for Now

The Words of Gad the Seer may merit more attention in the Latter-day Saint community, in my opinion. The text has a fascinating story and there may be more to learn from elements that might give us new insights into ancient Jewish thought. There may even be implications for the Book of Mormon. The peripheral issues of writing on metal, of ancient records in Yemen, and the ways in which sacred writings can be corrupted or neglected are fascinating in their own right, but there may be some gems of insight to extract from the text. More treasures from Cochin may yet remain to be discovered.

Related Resources:

Barbara C.. Johnson, “NewResearch, Discoveries and Paradigms: A Report on the Current Study of Kerala Jews,” in N. Katz et al. (eds.), Indo-Judaic Studies in the Twenty-First Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230603622_8 and https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9780230603622_8.

If you subscribe to the Biblical Archaeological Society, there are a number of articles on the issue of lost books:

-

- Duane Christensen, “Lost Books of the Bible,” Bible Review 14, no. 5 (October 1998).

- Tony Burke, “‘Lost Gospels’—Lost No More,” Biblical Archaeology Review 42, no. 5 (Sept./Oct. 2016).

As far as I can tell, the first western account of metal plates among the Jewish and Christian communities of Cochin comes from Damião de Góis in his "Three Letters of Mar Jacob". Mar Jacob, the Bishop of the Thomas Christians between 1543 and 1545 mentioned two copper plates with inscriptions in Pahlavi, Cushic (sic) and Hebrew script. These plates are unrelated to the chronicles of the Cochin Jews that were said to have been destroyed when the Portuguese burned down the synagogue in 1662 AD. This history was inexplicably called the sefer ha yashar or the Book of the Upright One or the Book of Jasher.

The elders of the Jewish community in Cochin had told Claudius Buchanan that they brought texts with them from Senna. It's unclear to me whether this is Sanaa in Yemen, or another Sena that is mentioned in the oral histories of other Jewish groups throughout the Indian Ocean, such as the Lemba of Zimbabwe.

"The Lemba are a traditionally endogamous group speaking a variety of Bantu languages who live in a number of locations in southern Africa. They claim descent from Jews who came to Africa from “Sena.” “Sena” is variously identified by them as Sanaa in Yemen, Judea, Egypt, or Ethiopia. A previous study using Y-chromosome markers suggested both a Bantu and a Semitic contribution to the Lemba gene pool, a suggestion that is not inconsistent with Lemba oral tradition."

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0002929707634399

Buchanan was told that there were at least 65 Jewish settlements beyond Cochin, extending from India to China. I've been doing quite a lot of research on the metal plate traditions and shared mythologies through the trading ports of Cochin-China and the islands of the Indian Ocean. A lot to unpack there.

Interesting post. I just purchased a paperback edition.

Steve

Zosimus, thank you for that valuable information. A little information about the plates of Mar Jacob has been discussed by Georg Schurhammer in The Malabar Church and Rome during the early Portuguese period and before (Trichinopoly [the British India name for Tiruchirappalli city in Tamil Nadu], India: F.M. Ponnuswamy 1934), p. 22, available at https://archive.org/details/malabarchurchrom00schu_0/page/22/mode/2up. It discusses several plates, some now lost. Fascinating!

The "Three Letters of Mar Jacob" are reproduced in Portuguese and translated to English at the side in Schurhammer's book, The Malabar Church and Rome during the early Portuguese period and before, with the mention of a copper plate found on p. 14. There is further discussion of this on pages 22-23 (esp. footnote 69), viewable at https://archive.org/details/malabarchurchrom00schu_0/page/22/mode/2up. The mention of a copper plate in the second Portuguese letter has "do que temos hua [dua?] lamyna [lamina] de cobre asselada de sseu sselo," with the given translation "of which we have a Copperplate sealed with his seal" (p. 14, emphasis original).

There's another reference I'd like to track down: Schurhammer, G., 1963a. “Three Letters of Mar Jacob, Bishop of Malabar, 1503-1550”, in Schurhammer, G., ed., Orientalia, Rome, Institutum historicum Societas Iesu; Lisbon, Centro de Estudos Históricos Ultramarinos.

For what it's worth—footnote 69, p 23

Schurhammer's book, The Malabar Church and Rome during the early Portuguese period and before:

()6 Much has been written about the Copperplates of Mar Jacob, also called the Thomas Cana Plates. (ves gives their description: “ Ha scriptura era Caldeu, Malabar, e Arabio. Estas taboas sao de metal fino, de palmo e meo cada hua de comprido, e quatro dedos de Jargo, scriptas dambalas bandas e infiadas pela banda de cima” (1,98). Then he gives a summary of the contents adding, that a Jew deciphered them with great difficulty and translated them into the Malabar tongue, from which they were translated into Portuguese and a copy sent to Portugal, but that he could not find it in the National Archives and that the original must still (1558) be in tle Factory of Cochin. Couto gives the text according to the Jew’s translation (12, 2, 5, 283-85) and says, that on his arrival at Cochin (1559) he still found the originals in the Factory, but that of late (he writes in 1603) they had disappeared (7, I. 12, 15’. Roz in 1604 gives the same text, somewhat fuller, “ fol- lowing a copy left in India, as the Franciscans had taken the originals to Portugal” (Relacao 86v-87v). But when the Copperplates of Mar Jacob disappeared, a “new set” was discovered in the possession of the Christians of Tevalacara near Quilon. Gouvea writing in 1603 deploring the loss of the former set tells us, how Archbishop Menezes in 1599 saw at Tevalacara a set of 3 plates, with writing on both sides, joined by a ring, 2 palms long and 4 fingers broad, containing the privileges of the Quilon Church, writ- ten in different letters and characters, Malavar, Canarin, Tamul and letters of Bisnagaa”’ (Jornada do Arcebispo de Goa D. Aleixo de Menezes, Coimbra 1606 1. I, c. 2). Roz adds, that the Plates were in the possession of the “ tarega ou rendeiro de Teualicare [tarega or tenant of Teualicare]” and that he, Roz, in 1601 had a translation made by cassanar Etymana, of which he gives a summary (Relagao 8cv). 1037 Plates dealing with the privileges of the Mani- gramam Christians are partly engraved on stone in Quilon (in the actual Jacobite Church: see T. K. Joseph, Malabar Christians and their ancient documents, Trivandrum 1929, App. VI!), In 1758 Plates are again mentioned in or near Quilon in the possession of schismatics (Germann, Die Kirche der Thomaschristen 228, Kerala Society Papers 4, 1 (continued)

92). The Mar Jacob (Thomas Cana) and the Tevalacara Plates mentioned above are regarded as lost (Joseph, Malabar Christians 32). We, however, incline to the following hypothesis: The measures given by Goes and Gouvea are rough estimates; the descrip- tion of Pero de Siqueira given after his return to Portugal and reproduced by Goes is perhaps partly incorrect as is his statement about de Sousa; the “translation” of the Jew, reproduced by Couto and Roz, is fantastical, giving one or other well or half understood word and for the rest the oral tradition of what the St. Thomas Christians thought the plates contained; and the Mar Jacob Plates are identical with the Tevalacara and these with the Quilon Turisa Plates IJ, described and partly deciphered in the Travan- core Archaeological Series (Trivandrum 1920) If 70-85 and belonging to the time of king Sthanu Ravi (end of 9th century). Of these Plates No. I is missing, II and III are in the old Syrian Christian Seminary of Kottayam (since Micaulay 1806), IV in the palace of the bishop of the Mar Thomas Syrian Christians at Tiruvallé. Plates II and III, written in Vatteluttu and Grantha letters are in Tamil and contain the donation of land by the King of Quilon to Maruvan Sapir Is), the builder of the Tarisâ Church at Quilon, and the concession of privileges to the Anjuvannam and Manigrimam communities. Plate IV gives the signatures in Pahlavi, Kufic and Hebrew. The text is “full of unintelligible words and phrases” and the signatures have only partly been deciphered The following dates agree in the Mar Jacob, Tevalacara and Quilon Plates, which we call shortly A, B and C, (an English translation of Couto’s and Koz’ text is given in the interesting monography of the Kerala Society Papers 4,189):

John S. Robertson

Fascinating. Thanks for the detailed information. Will definitely buy the book.

Robert Cheeseman, professor at BYU in the 1960s to ? and archeologist, was on a dig deep in Peru jungles in 1968 if recalling correctly. Many wonderful artifacts were found. A few plates of gold were found with writing on them. The Peru government gave permission for the plates to be replicated and the replica is on display at the BYU library.

The foil sample from Peru has 8 symbols on it (image at https://nephicode.blogspot.com/2020/06/cheeseman-artifacts-and-andean-peru.html). Are they writing or artwork? Not sure. Genuine or a forgery? Fair question. It is noted in Ray Matheny's work with the fraudulent Padilla plates from Mexico that the Padilla plates are almost pure gold, unlike the more reasonable mix of gold, silver, and copper in the Peruvian foil, and that the Padilla plates are extremely smooth as happens in modern manufacturing methods, in contrast to the rougher hammered surface of the Peruvian foil. See Ray T. Matheny, "An Analysis of the Padilla Gold Plates," BYU Studies Quarterly 19, no. 1 (1978): 21-40. The PDF is at https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byusq/vol19/iss1/4/ and an HTML version is at http://www.bmaf.org/articles/padilla_plates__matheny. That doesn't mean the Peruvian sample is an authentic ancient product, or if ancient, that the symbols on it contain genuine writing. Have they even been dated? I'm not sure.