Many Latter-day Saints seem unaware of the great body of scholarship that can strengthen faith and understanding for members of the Church and those exploring it. Such scholarship can be found at sources like FAIR, Scripture Central (including Book of Mormon Central), and Interpreter: A Journal of Latter-day Saint Faith and Scholarship. I’ve encountered some members who shrug their shoulders and say things like, “That may all be interesting, but we don’t need work from scholars to help us understand the scriptures — all we need are the plain teachings of the standard works.” When it comes to the specific mountain of fascinating research from Royal Skousen on the intricate details of the Book of Mormon text in light of the Original Manuscript, the Printer’s Manuscript, and various changes over time in the Book of Mormon, some seem to have a related attitude: “That may be interesting, but surely nothing of importance depends on the work of scholars.”

If you encounter this attitude, here’s one simple example that may open minds to the importance of modern scholarship from sound, faithful scholars. In Alma 39:13, Alma is guiding his wayward son, Corianton, who committed a serious moral sin while serving on a mission to the Zoramites. Alma implores his son to return to the Lord and stop leading people away into wickedness, “but rather return unto them and acknowledge your faults and that wrong which ye have done.” So it sounds like Corianton’s path to repentance is pretty much acknowledging to those he harmed that he was wrong. That’s how it reads in our current edition of the Book of Mormon, and it’s been that way since 1920. But prior to 1920, it was even more disconcerting, for there, Alma told Corianton to “acknowledge your faults and retain that wrong which ye have done.” Retain a wrong? Retain his sins? What’s going on?

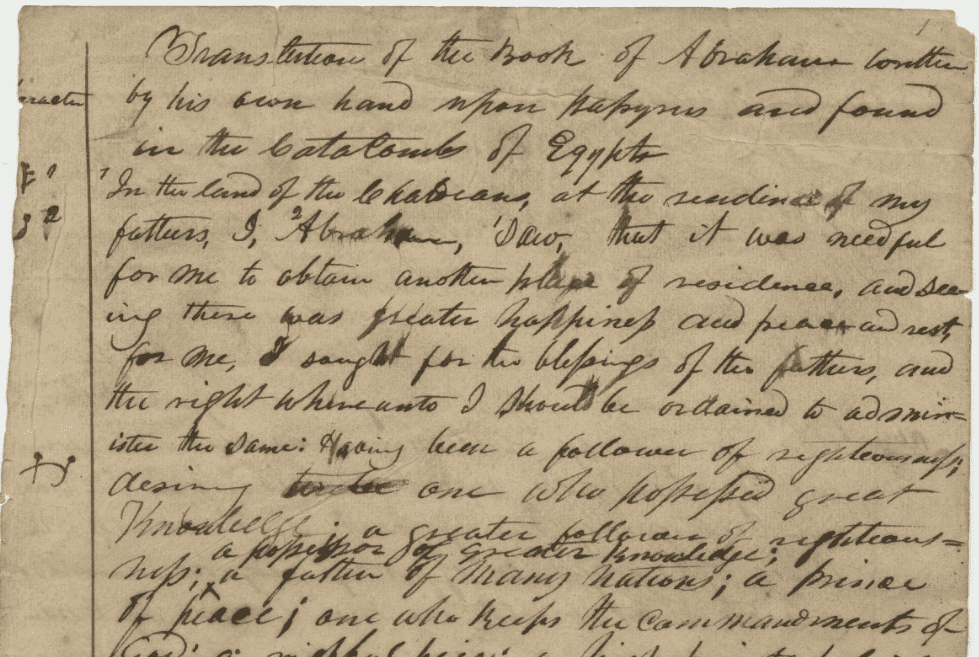

Here’s where the modern scholarship of Royal Skousen resolves the problems and helps us appreciate the internal consistency of the remarkable text that Joseph Smith dictated. See his presentation, “Do We Need to Make Changes to the Book of Mormon Text?” at the 2012 FAIRMormon Conference. Skousen notes that we have the Original Manuscript for this passage, making it part of the lucky 20% of the Book of Mormon for which the Original Manuscript is extant. Careful examination of the manuscript shows that what Oliver Cowdery wrote as he took dictation from Joseph Smith was “acknowledge your faults and repair that wrong which ye have done.” However, he also spilled some drops of ink on the word repair, making the “p” look like a “t.” Thus, when Oliver created the Printer’s Manuscript, he concluded that the word must be “retain.” That word stuck for decades, and finally in 1920 this illogical, confusing word was simply removed, giving us what sounds more like cheap grace for Corianton rather than the normal expectation that sinners strive to make up for the harm they done as in Mosiah 27:35 and Helaman 5:17. The latter verse has “to endeavor to repair unto them the wrongs which they had done,” giving wording very similar to Alma 39:13 in the Original Manuscript.

Through modern scholarship, we can see that there are further corrections that need to be considered in our current Book of Mormon, beyond the need to repair Alma 39:13, as Royal Skousen has indicated. The change that conforms to the Original Manuscript has been made in his outstanding book, The Book of Mormon: The Earliest Text (New Haven and London: Yale Univ. Press, 2009). The lightly modified second edition came out in 2022, but is not yet available in Kindle, just the first edition.

When understood in light of scholarship on the text of the Book of Mormon, we can see that Alma’s instructions to his son required more than simply admitting error. His instructions are consistent with the rest of the Book of Mormon. This has doctrinal significance. This episode reminds us that the scriptures, in spite of being inspired of God and even having miraculous origins, go through the hands of men and are subject to human errors. In this case, we are fortunate that human scholarship has been able to give us some valuable guidance that helps us better appreciate the consistency and accurate teachings of the Book of Mormon. Scholarship matters.

Here is the video of Royal Skousen’s 2012 presentation, “Do We Need to Make Changes to the Book of Mormon Text?“:

“We believe in being subject to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates, in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.”

Feds fine Mormon church for illicitly hiding $32 billion investment fund behind shell companies

David, I recognize that the media is making hay with this story, but it’s really about a reporting issue that was fixed three years ago. It’s about an investment firm, not the Church, not filing reports in the way the SEC prefers. It’s not about illegal or fraudulent behavior. So yes, in spite of a technical error in report by a third party, the behavior of the Church remains one of sustaining and following the law, not violating it as you imply. Here’s part of the information provided at Public Square Magazine in their article, “Ensign Peak: Clarifying the SEC Announcement” from Feb. 21, 2023:

But yes, it looks like there was an attempt to protect privacy by having their investment fund split up their portfolio among multiple shell companies. See the Church’s response of Feb. 21, 2023 at “Church Issues Statement on SEC Settlement.” Protection of privacy in this way does not mean that taxes were evaded or fraud committed. I’d personally prefer that private organizations and individuals be able to keep their more of their financial matters to themselves, but I guess it’s increasingly difficult to do these days.

Jeff, I admire your dedication to the firm. I expected nothing less. But those of us not similarly disposed have to laugh at your spin . We’re not talking simply about “a technical error in report by a third party,” we’re talking about 20 years of consistently structuring investments so as to avoid legally mandated transparency.

Nor are we talking about “protecting privacy.” Major market movers like Ensign Peak are not entitled to privacy. For good reason, the law requires transparency. In this context, we don’t use the word “privacy,” we use the word “secrecy.” You might as well say “The bank robbers opened a series of $9,900 savings accounts in order to protect their privacy.”

Did EPA pursue secrecy “on the advice of its attorneys”? No doubt it did. And guess what? Corporate attorneys often give advice that amounts to “Here’s what the law says, and here’s what you can get away with, and here’s the paltry amount you’ll be fined if you get caught.” That’s not at all the same thing as honoring the law.

Finally, I suggest you read the Church’s announcement more carefully. If you do, you will better appreciate it as a masterpiece of legalistic PR. Note that it nowhere actually denies that EPA broke the law.

If something like this had happened at my own Jewish temple/center, heads would be rolling. We have certain expectations of our leadership.

I attend a church, not a “firm.” Saving money successfully does not make a religion a business.

I didn’t say I’m happy with this. But making errors with extremely complex tax codes happens many times. In this case, there’s nothing to suggest that the mistake indicates a crime was committed. But certainly what was filed was a mistake, and none of us are happy with that. It seems that to protect privacy — and that was apparently the goal, and a legitimate one for all of us — the funds should have been invested in more than one firm with no interconnections. Would there be anything wrong in that case?

The PublicSquare Magazine articles make this important point:

“Errors” lol.

Happy or unhappy, Jeff, you’ll still defending the church’s deliberate and repeated actions to avoid legally required transparency about its assets. Call failing to file disclosures sloppy if you wish but why was it necessary to create all those shell corps?

I honestly doubt you’d handle your own dealings in the same way and this is certainly not what the church requires of members when it asks “Do you strive to be honest in all that you do?” Similarly, when it asks “Are you a full-tithe payer?” we might ask when it comes to “paying to Ceasar” as Jesus taught, why the church should be excused its repeated and calculated failures.

This is a trust issue, pure and simple. Ensuring that members were ignorant of the church’s assets so tithing payments wouldn’t be compromised is not a way to engender trust. The failure here is moral, not financial.

The actions you complain about ended three years ago. The motivation for spreading the funds around was privacy, and it’s a fair motivation for any church or individual. This was not about tax evasion, as you imply. There are no implications that taxes were evaded or fraud was committed. It’s fair to describe the approach taken as an error, maybe a serious one, even the SEC isn’t calling it fraud or tax evasion. People like you and me may make many errors in seeking to legally reduce our taxes (or protect our privacy) in light of extremely complex tax rules, and such errors may not reflect a serious moral problem. In this case, the most reasonable way to understand this case is that actions resulting in the fines were motivated by privacy, though you are free to guess insidious motives that fit your narrative.

The amount that any church or any individual has saved should not be not the business of government. I don’t have a moral obligation to tell you what I have saved. But I can see the SEC’s point that for large amounts that might influence the market, they want to know when one investment firm is handling a large amount to prevent improper market actions. It would seem, then, that it would have been better for the Church to spread investments among multiple firms rather than have one firm manage it all and use multiple shell companies to seek that privacy. But there’s a not a moral or legal requirement that I know of for all assets of a religion or individual to be disclosed to government officials. There’s no genuine moral issue here, though many people naturally would like to know all sorts of details about organizations they don’t like. But there’s no moral obligation to tell all that to the public. The fundamental issue here is one of financial reporting errors.

Perhaps you think it’s a tax issue because I said “pay to Caesar”. If you’re literal that might be payment of taxes but if you consider it more generally it could just as well mean following official responsibilities and reporting fully and honestly.

This is an issue of honesty and trust and it seems pretty clear your church has broken faith with the SEC, the investment community and the membership since part of their motivation was simply refusing to disclose the extent of their wealth.

It appears your church has an obsession with secrecy. Secrecy of rituals, reporting sex crimes and now required filings. Pretend there were “errors” if you like. Let’s see how long you can keep up the ruse in your own mind.

Dear anon,

If you are all in for transparency, why is your name “anon?”

John S. Robertson

If I use my full name will you know anything more than you did when I used anon? Does knowing that you post as John S. Robertson tell me anything of value? And would a name change one thing about the duplicity of the church?

All anons on the internet hide themselves from accountability. It licenses them to say things they otherwise might not say to our faces. Accountability alone is the depurate that invites truth. Know how I know? I’ve been called, you know, names under the shade of anonymity.

John S. Robertson